Agroecology, from Palestine to the Diaspora

By Nadine Fattaleh and Adam Albarghouthi (Tran./Ed.)

With the participation of Saad Dagher, Mohammad Khweirah, Muhab Alalami, Adham Karajeh, Arafat Barghouthi, Rami Massad, Qays Hamad

Volume 25, no. 1, The Soil and the Worker

This article is copublished by Jadaliyya in Arabic | تم نشر النسخة العربية لهذا المقال بشراكة مع مجلة جدليّة

On a biweekly basis, you’ll find a farmer’s market set up on tables laid out in front of the cultural center in Ramallah. A number of agricultural cooperatives from the surrounding municipalities come to sell their organic produce to passersby and to regular customers that come out in their support. Most of these cooperatives are youth-led farms inspired by a surge of interest in new models of community-supported farming using agroecological methods.

This farmer’s market isn’t just a place to buy organic produce, it’s a place to get a taste of what’s to come. The Palestinian youth today are paving the way toward establishing food sovereignty and reducing dependence on the products and employment of the occupation. They uphold their values and principles through a cooperative organizational model centered on equity amongst farmers themselves, and between farmers and their community.

We share with you below a transcript of a webinar that brought together various individual and collective initiatives working in alternative farming from across Palestine and the diaspora.

Introduction

Saad Dagher: I am an agricultural engineer, and I’ve been in the field of agroecology since 1996. In 2007, I started the Humanistic Farm, which went through different phases and has enriched my experience. I oversee my own farm, and I conduct training for farmers and agricultural engineers in Palestine and around the world. I worked in Yemen and Jordan in 2003, then I moved on to work in Morocco, Lebanon, and Portugal. Three years ago, I initiated, with friends and colleagues, the Palestine Agroecology Forum, and we inaugurated February 23 as the Palestinian Day of Community-Supported Agroecology. We convened several conferences on the topic through my work with the Arab Union of Agricultural Engineers. Concurrently, I started working on collecting, preserving, and developing local seeds. I am currently establishing an initiative called Khabiyeh, to share and expand local seeds with communities of farmers. I am a member of several international movements on farming and environmental conservation.

Mohammad Khweirah: My journey in farming started three years ago, on an ad hoc basis, through participating in numerous trainings and building on my mother’s rich knowledge of agriculture. I am involved with a number of initiatives. The first is the Peasant Farm “أرض الفلاح”, a private family farm I work on with my brother Abdullah. I am a member of the Peasants Land Cooperative “تعاونية أرض الفلاحين” in Kufr Ne’emeh, where I mainly advise on various technical aspects like the production of organic fertilizer. A few months ago, I joined Om Sleiman Farm, which runs a community-supported agriculture program. In general, we strive to produce a large amount of fruits and vegetables with the lowest production price, through reducing our reliance on external inputs. We are also slowly learning, in West Ramallah, various ways to market our products. Our mothers were initially our sales representatives, encouraging their friends to buy our products through word of mouth. Recently, we’ve turned to setting up stalls in the village, and things have been surprisingly positive, where sales on good days can amount to 900 shekels (280 USD). My primary concern is to cater to our village of five to six thousand people. Currently, we are trying to centralize a community to share agricultural inputs for all the farms in the area.

Muhab Alalami: I am the founder of Om Sleiman Farm along with Mohammad Abujayyab, who is a refugee from the Gaza Strip. When we first thought about starting a farm we had no money, but Mohammad was influenced by the Community-Supported Agriculture model. We got a piece of land, and the first season we produced for eight families, then ten families, and today, we serve sixty families. The farm is in a village called Bil’in, bordering the occupation wall. I am excited to share our experience and to learn from others in overcoming our challenges in production, marketing, and perhaps the community is at the core of it all.

Adham Karajeh: I am from Saffa village, and I’m a member of Ard Al-Ya’as “أرض اليأس” (Land of Despair) Cooperative. Our cooperative started at the end of 2017, with four people, and now it’s extended to include sixteen people. We developed from Ba’ali, or rainfed agriculture, to irrigated-open fields, and today, we cultivate crops inside greenhouses. To continue to survive, we constantly evolve and learn through training and visits to other farms. Land of Despair, as a name, is derived from Nietzche’s understanding of despair as the price paid to acquire self-awareness. In this world, it seems the more we know, the more despair we feel, but at the same time, we use this despair to fuel a productive path towards the future. Our aim is to develop the cooperative, and to reach our social goals, to enshrine communal values, and instill a reciprocal relationship with nature.

Arafat Barghouthi: I am from Deir Ghassaneh, a village in Ramallah. I am involved with Ard Kanaan “أرض كنعان” (Land of Canaan), a humble initiative which started two years ago. We are a group of young people, most of us former detainees. We thought of ways to work in this country, to establish economic and job security, while serving our nationalist message. We rely on our land and labor, away from the culture of consumerism that is taking shape in Palestine. Our cooperative is involved in poultry farming, producing eggs and chicken meat that drives consumers away from a reliance on the occupation. On our 9 dunum (appximately 2.2 acre) piece of land, we’re also growing fodder for our chickens, and to market to Palestinian farmers more broadly in support of self-sufficiency in organic, non-chemical fodder consumption, reducing the need for imported inputs from the occupation. We are experimenting with five different plants that can be used to produce fodder, and we’re hoping to mechanize the process in the future.

Rami Massad: I represent the Youth Partnership Forum, an umbrella organization bringing together a number of youth initiatives working in the West Bank and Gaza, inside of Occupied Palestine and across the diaspora. Activists gather through our national committee to set agendas and priorities for our work, and one of these issues is the cooperatives. We all agree that it’s an economic and social alternative precinct to our national aspirations in the context of Palestine. We insist on a popular appeal to ensure the sustainability of our project. On the ground, we offer a space for cooperatives to share, learn, and develop their experiences, offering holistic interventions that range from raising awareness to providing administrative and agroecological training to farmers. In recent years, we have organized markets in the municipalities depending on the needs of small farmers, in addition to a year-long biweekly farmers market in Ramallah offering organic products at a fair price. We also mobilize a support circle called friends of the farmer to offer immediate support and relief to agricultural cooperatives in emergency situations. This ensures the autonomy of their work away from foreign funding. We are currently exploring expanding this to a cooperative fund that provides insurance and protection that sustains the continuity of small farmer initiatives.

Qays Hamad: I am a doubly displaced Palestinian originally from Tiberius, and currently residing in Greece, where I work with a cooperative established a year and a half ago called Hakoura. We started Hakoura because we believe that as Palestinians, we are deeply connected to the land. Faced with a stifled economic situation in Greece and the absence of a refugee integration program, we turned to cooperative agriculture to generate a livelihood. We learned from our Greek friends, who also took to farming in times of economic collapse. Through our networks, we found fertile agricultural areas that resemble the soils in Palestine. We rented a piece of land and grew fruits and vegetables for the first season, but our experience was interrupted because the price of production, especially the cost of the vehicle that moves produce from the countryside to the city, was too high. We’ve just bounced back and rented another 10 dunum (approximately 2.5 acre) plot with a water well. This was largely through the support of a crowdfunding campaign predicated on solidarity and not charity; allowing us to continue farming away from donor organizations and their strictures. As we try to stand on our feet, we feel energized and motivated by our connection and collaboration with other young farmers and cooperatives in Palestine. We must continue to maintain our connection to the homeland, and farming in Greece is our own form of return to our villages, through planting local seeds to smell and taste Palestine.

Why cooperatives, why agroecology? Are they really economically viable?

Qays: Why cooperatives? In general, I prefer the cooperative to formal employment. When you are a member of a cooperative, rather than a worker, you feel a sense of ownership over the project. The more you produce, the more you’ll be able to take home to your family. You are autonomous, there is no manager, feudalist or capitalist controlling you. There is more dignity in cooperation, and more production, too.

Mohammad: What I value about agroecology is it produces, quite simply, tastier fruits and vegetables with rich flavor. All our customers believe this! Secondly, agroecology is predicated on developing a holistic system that doesn’t require external inputs. You have trees, seasonal bushes, and animals, and they can exist in a harmonious, symbiotic relationship. As farmers, we are not industrialists and we do not exist in a laboratory setting. We utilize everything that is available around us: this is why we have chickens, we don’t throw away weeds, and we try to reuse everything. Of course, we work on small tracts of land. But there are studies and research proving the efficacy even of large farms that work to integrate natural resources with the labor of farmers and the work of machines.

Muhab: Om Suleiman farm is not a cooperative, with all my respect to cooperatives. We considered becoming a cooperative, but since it requires registration, and some degree of official oversight, we decided we have no faith in the administrative mechanisms around us. We believe in the essence of cooperatives, in working collaboratively and challenging capitalist hegemony. In terms of agroecology, it is cheaper because it requires no fertilizer, and works through mimicking nature. Agroecological methods are highly productive, and it’s a myth that it produces less yield. One challenging aspect I’ve found concerns the shelf life of fruits and vegetables. For example, most of the tomatoes you eat are either hybrid or genetically modified, and this is to economize shipping processes for produce that lands in your supermarket. For small farmers like us, agroecology is more suitable to the context, it guarantees independence and it’s the future of agricultural sovereignty.

There can be no liberation if we don’t have sovereignty over our daily bread. Agroecology is a way towards food sovereignty, which can then enable us to consider questions of political liberation.

Saad: I increasingly lean towards distinguishing between agriculture and farming. Agriculture is an occupation but farming is a way of life. We need a different way of life that centers the production of food. Farming also encapsulates social relations. Here’s where I get to the cooperative model. The idea of cooperation is about working together. What turned us away from the official cooperatives is the distortion that happened in the context in Palestine, as a result of development organizations, and later the Palestinian Authority. Having worked with several of these organizations, I can testify to the negative role they played in obfuscating the very idea of cooperation under the cooperative model. The cooperatives present here, like Ard Al Ya’as and Kufr Ne’emeh, differ from officially registered cooperative societies. Their ideologies and practices are different.

Why agroecology? There’s the nationalist bent, and I always question, as a person, what I can do for my country. I promote the conviction that we need a model of food production without relying on the occupier. For example, all chemical fertilizers that enter our market are controlled, in one way or another, by the occupier. There can be no liberation if we don’t have sovereignty over our daily bread. Agroecology is a way towards food sovereignty, which can then enable us to consider questions of political liberation.

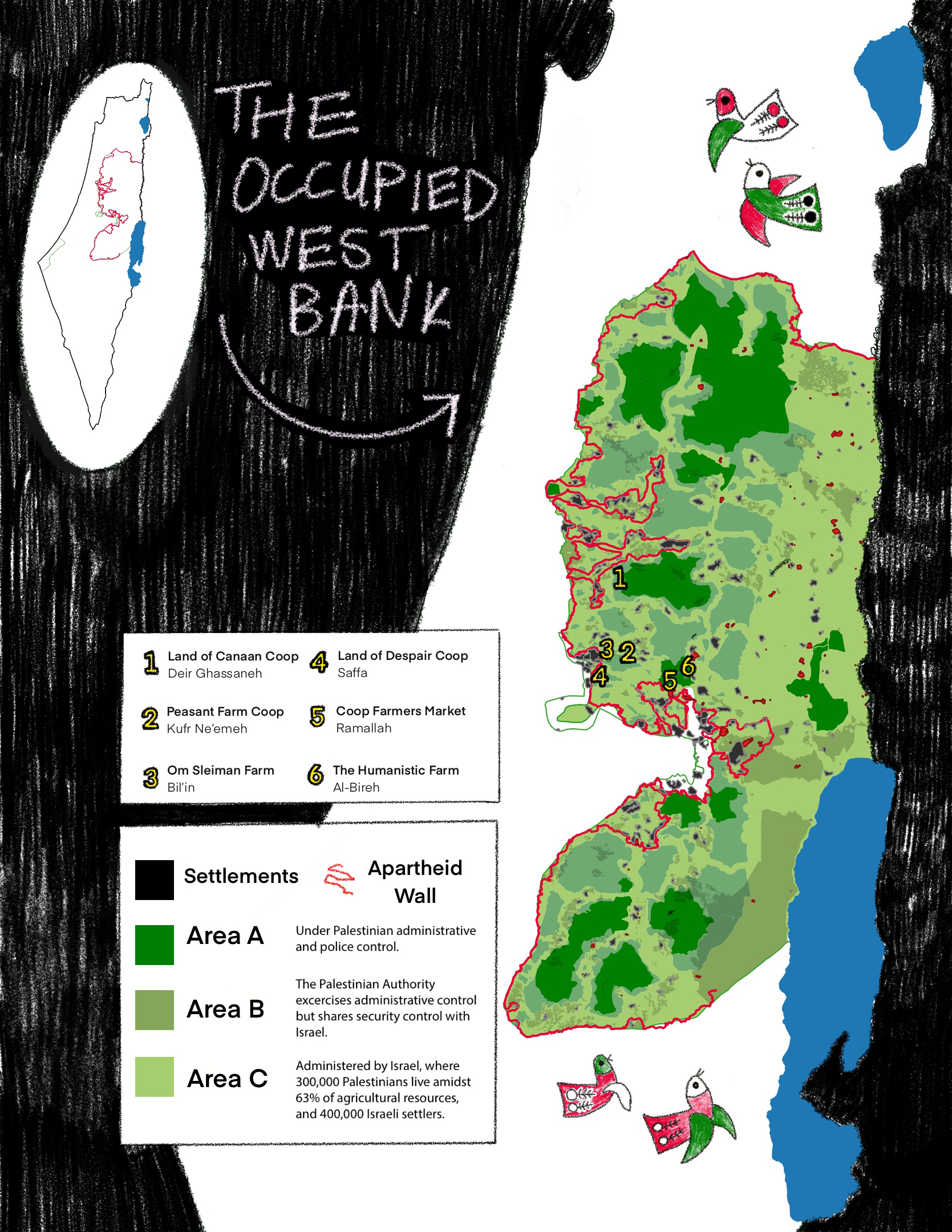

Rami: The idea of cooperatives in Palestine is not new, the first was established in 1924. Cooperatives have long played an important nationalist and economic role in the country. Things changed with the establishment of the Palestinian Authority after the signing of the Oslo Accords, and the influx of foreign funding. Land is the essence of our struggle with the occupation. We know about the settlements and the Apartheid Wall. The protection of land is our real duty. We must do this in concrete ways and not through empty speeches and slogans. The economic aspect has been addressed. The consumerist model is necessarily tied to the cleaves of the occupation. How can we talk about a solidarity economy of resistance when we don’t have any production? How can we boycott the occupation’s goods without producing alternatives? On a social level, the current moment dominated by the PA’s policy, and international donors to a lesser extent, promotes a culture of individualism. This is reflected in our current way of life. This is why it’s important to rethink a collectivist model, to go back to solidarity and mutual aid. We need to think about collective liberation, and not individual liberation.

What are some of your successes or challenges?

Rami: Our economy is under occupation. The market is open, and perhaps flooded by Israeli products with the consent of the Palestinian Authority. Palestinian famers and cooperatives face problems with marketing because the occupation’s products are cheaper. This is a problem, and the solution starts with a popular appeal for supporting Palestinian produce.

Two years ago, Israeli watermelon’s flooded the Palestinian market and undermined the price. Farmers in the Jordan Valley left their watermelon in the fields, reasoning that the additional price and effort of the harvest will not be compensated by the distorted market price. When grassroots organizations mobilized to support the farmers, advertising the watermelons in various municipalities, thirty tons were sold. The fruits and vegetables that arrive in shops and supermarkets don’t have tracing codes: there is no indication if this is Palestinian or Israeli produce. There’s the political dimension to limiting the smuggling of Israeli goods into Palestinian markets, and setting limits on imports, but these are far fetched, as they are tied to diplomatic agreements. This is why we rely on popular awareness in marketing, and we’ve seen huge success with the local farmer’s market in Ramallah. We need to study the possibility of expanding this to all municipalities, and to continue to look for avenues to connect with the masses.

Arafat Barghouthi, In Palestine, we are forced to consider the political ramifications of all aspects of our lives. After Oslo, with the rule of the Palestinian Authority and the arrival of nongovernmental organizations, our values of cooperation and mutual aid have come under attack. The cooperatives have allowed us to maintain our connection to the land, and to rebuild collectivist notions of solidarity amongst our workers and those who have supported us and provided us moral grounding. Our farm is now a madafeh, or a communal space that welcomes visits from all class backgrounds and political inclinations.

Qais: Working in Greece, we initially assumed we needed to work according to the demands of the market. The European Union market for organic produce is very big and quite competitive. With time, we started to learn new ways for marketing. One of our cooperative members once shared a simple link for signing up for weekly or monthly produce boxes, developing a Community Supported Agriculture model. We found an outpour of solidarity from Greek citizens who are neither our neighbors nor acquaintances, but who signed up and supported us nonetheless. All cooperatives need to adapt to their contexts, to managing online subscriptions or working with shops and markets.

Saad: The main challenge I fear is the potential damage of official institutions. Agroecology is threatened by development and donor organizations, or anyone who might potentially work with agroecology on a shallow level. There’s a question of maintaining all the central tenets of agroecology, based on a productive, cooperative, and liberatory model. Fifteen years ago, no one cared about agroecology. Today, people might suggest combining agroecology with the use of genetically modified seeds. Others see that agroecology has become a catchphrase that attracts foreign donors. We need to remain vigilant about these potential challenges, and to remain committed to a popular support for the holistic application of agroecology in Palestine. ♦