Weaving the Threads of Commoning

By Michelle Wenderlich

Volume 24, no. 3, Cooperation: Theory and Practice for the Commons

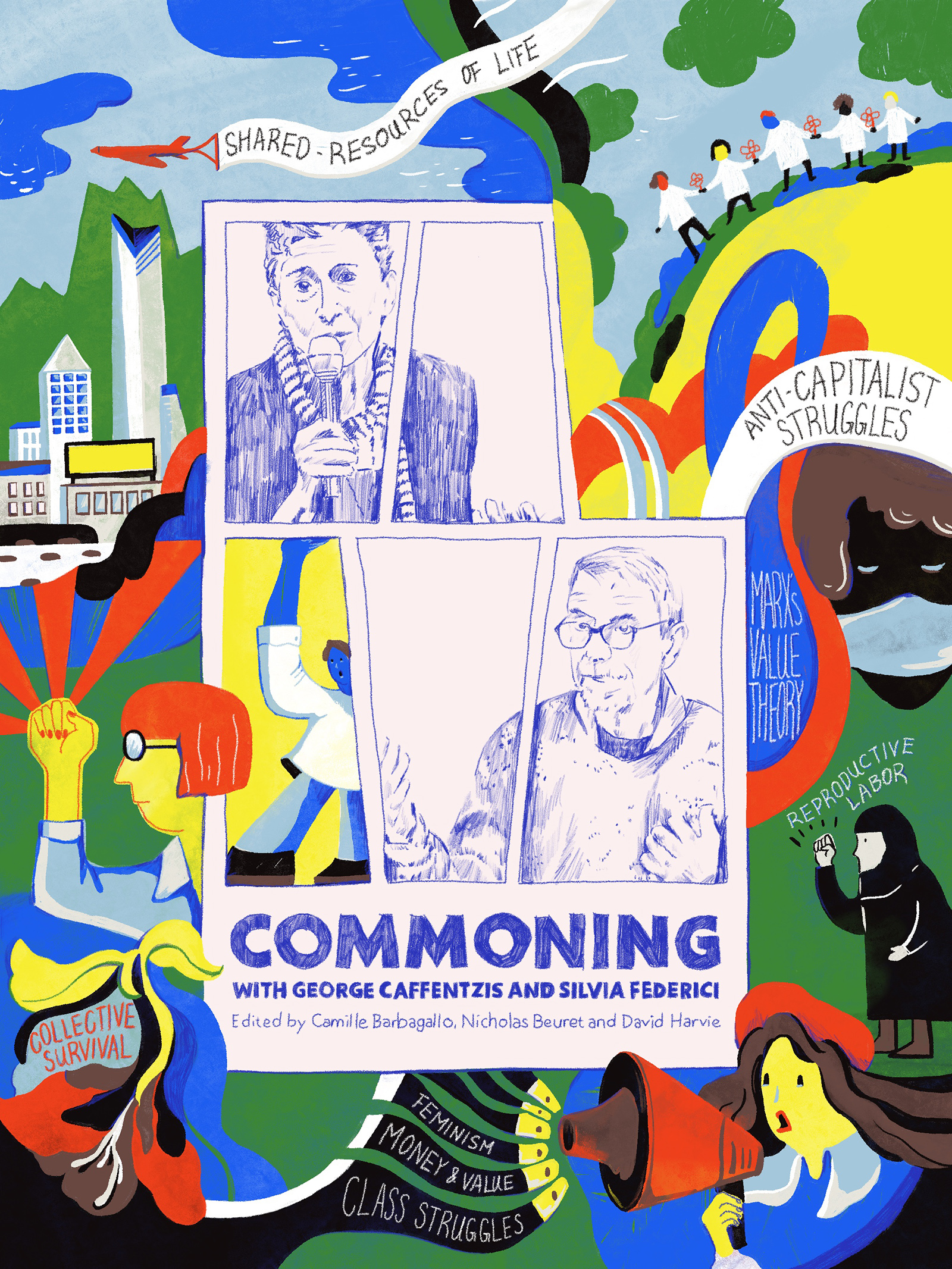

Commoning is an edited volume of articles written by various Marxist and feminist thinkers, movement practitioners, historians, and academics, including Peter Linebaugh, Raquel Gutiérrez Aguilar, Stevphen Shukaitis, Nick Dyer-Witheford, Marina Sitrin, and many more. Together, they cover a wide range of topics from “revolutionary histories,” “money and value,” and “reproduction” to “commons” and “struggle.” What brings these authors of various stripes together? They have all been influenced by George Caffentzis and Silvia Federici.

Caffentzis and Federici have been major figures since the 1960s in the intellectual development and propagation of, and active struggle for, various movements, including the feminist, antiwar, alter-globalization, decolonial, Zapatista, and Occupy Wall Street movements. They are especially renowned for their work on social reproduction, specifically for connecting the history of capitalism and colonialism with the assault on womens’ bodies, rights, and freedom, as well as questioning the nature of work and class struggle in daily life. In addition, as the title of the edited volume suggests, Caffentzis’s and Federici’s work often revolves around the concept of commoning.

Commoning is the social and daily practice of self-organization to meet people’s needs and desires. Anti-capitalist commons in particular are autonomous from the market and the state; they could be seen as an alternative social form to capitalism.1 Influenced by their time in Nigeria during the manufactured debt crisis of the 1980s and across subsistence and village economies in the Global South, Caffentzis and Federici saw the enclosure of commons not only as singular historical events of forcing peasants off the land and into a wage relation or the mere precondition for capitalism, but also as exhibiting a “continuous character.” The enclosure of un-commodified collective resources of life for capital accumulation is always in dynamic contradiction to the practices of commoning that can find new ways of being and relating.

Commoning is thus the thread that binds these diverse articles together. In the piece that most directly presents a framework for commoning, Massimo De Angelis explains the framework for commoning to be, as Federici suggested, “the strategic site from which to envision a horizon of emancipation for all”:

Just as for Marx the commodity is the cell form of the capitalist mode of production, so the common good is the cell form of post-capitalist wealth, wealth-in-common, shared wealth. Yet this formulation does not tell us anything about how we share, nor how we produce and reproduce what needs to be shared in different contexts. These questions can be posed within a framework of the commons as social systems. Commons are social systems comprised of two sets of elements. First, the material and immaterial elements that constitute commons-wealth, what is shared; and second, the social relations among the people within these commons communities, the rules and norms, both formal and informal, they use to coordinate their actions and their social relations.

In another piece, Olivier de Marcellus asks big questions about organization and the relation of commons to the state. He brings up Alvaro Linera’s communitarian socialism, “in which the ‘illusory’ commons monopolised by a minority in the old State could be progressively reclaimed by organisations and communities,” to suggest that the state could be turned into commons over time. As experiments in direct democracy at the municipal level, De Marcellus points to “rebel cities” that seek to impose real democratic participation from the “outside” of the concentrated power of the old state.

The pieces in the book are quite varied, both in their subject matter and sometimes in their treatment of commoning. For instance, Edith Gonzalez critiques Federici’s view of the state and commons: “Federici’s theory of the commons recreates the image of a new emancipatory economic model based on reproduction in counterposition to the failed revolutionary goal of the conquest of state power, but without being able to overcome it.” In contrast, Marcela Olivera and Alexander Dwinell are fully convinced (along with Caffentzis and Federici) that the state must remain separate from commoning. They review their experiences in Cochabamba’s Water War and the attempt to gain social control of the public water utility: “Our approach is to seek to defend and improve the historical regulation of water access under the idea of usos y costumbres, an approach that is incompatible with the state and the framework of laws that define its existence.” They see state regulation of social life as another form of enclosure.

Other pieces are less explicit about the practice of commoning. One major takeaway is that commoning is a historical practice and ongoing locus of struggle, which offers an alternative system of value to capital and often starts with the unseen work of social reproduction. For example, Camille Barbagallo and Viviane Gonik bring up issues of care and reproductive labor to illustrate how paid and unpaid aspects of “productive” and “reproductive” work are connected, and how all have had a historical role in constituting current manifestations of race and gender. They examine the binary of paid/unpaid labor of enslaved people and women (and more recently of migrant women of color) and its connections to dehumanization and oppression. The typology of labor helped create stronger divisions between men and women, invisibilizing women’s paid work as well.

Continuing on issues of reproduction, Bue Rübner Hansen and Manuela Zechner address the practicalities of extending kinship and reproductive labor beyond the nuclear family in a piece that also examines kinship as a game that orbits (and creates) a field of belonging around its subjects through shared life and work. Marina Sitrin’s piece provides a clear summary of newer thinking about recent mass movements based in “prioritiz[ing] social relationships and care-based organising, and the focus on means as inseparable from ends.” These movements often create their own solutions rather than demanding them from the state, drawing on practices of the Zapatistas and those in Rojava who are creating autonomous and self-organized societies outside of and in opposition to the state.

The book also encourages us to expand our economic analyses and look at how social struggles and daily life (cornerstones of anti-capitalist commoning) affect the capitalist economy and dynamics of profit. Both Dave Eden’s chapter on capitalist energy crises and Nick Dyer-Witheford’s examination of theories of the end of work through robots and artificial intelligence take this perspective. In both cases the authors use Caffentzis’s writings to examine underlying dynamics of profit and struggle. Dyer-Witheford points out the role of “the tendency of the rate of profit to fall,” which equalizes an average profit rate globally, in staving off an AI takeover because unmechanized, labor-intensive production has still been cheaper in the Global South. However, Dyer-Witheford is less convinced that this tendency will hold going forward, when the underlying labor conditions might be shifting. Eden highlights the dysfunctionality of capitalist markets—which in Australia manifest in inflating energy prices and simultaneous non-investment in renewables—and also looks at exploitation of labor, crises of social control and uprisings, and dynamics of land ownership and political capture. What is common between these chapters is that they all circle back to anti-capitalist struggles.

How do we practice science as commoning, and what do reproductive labor, capitalism and colonialism have to do with it?

Depending on how much you have engaged with Caffentzis and Federici, and your area of interest, you are likely to pay more attention to one section than another. Like many edited volumes, this book goes in many different directions without drawing each idea out extensively. Instead, it leaves the readers to weave the common threads. The book presumes a certain level of familiarity with Caffentzis and Federici’s work and is mostly written in rather academic prose, which could be a barrier to some readers especially in the chapters about intellectual history and Marxist economics. But some chapters are more accessible, and if all else fails, there is also a comic and a short story included!

There are a few analyses that could be of particular relevance to the SftP audience. For instance, Sian Sullivan’s examination of the financialization of nature through the lens of Federici’s book Caliban and the Witch references commoning with respect to “natural” resources and critiques the commodification and enclosure of ecosystems.2 There are also several contributions that examine intellectual history and ideological tools of domination, such as Paul Rekret’s examination of Caffentzis’s work on Locke, Berkeley and Hume, and “how particular social relations, and monetary debates more narrowly, have shaped philosophy.” Readers might also end up contemplating how to practice science as commoning, and what reproductive labor, capitalism and colonialism have to do with it.

On the whole, this volume is an interesting way to gain exposure to different segments of Federici and Caffentzsis’s work and to what may be new insights about their significance and interrelation. It speaks to how we live our lives, think about capitalism and its alternatives, and fight for our future.

Commoning: With George Caffentzis and Silvia Federici

Edited by Camille Barbagallo, Nicholas Beuret and David Harvie

Pluto Press

2019

352 pages

Notes

- George Caffentzis and Silvia Federici, “Commons Against and Beyond Capitalism,” Community Development Journal 49, no. S1 (January 2014): i92–i105.

- Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body, and Primitive Accumulation (New York, NY: Autonomedia, 2004).