The Half-Life of a Nuclear Disaster

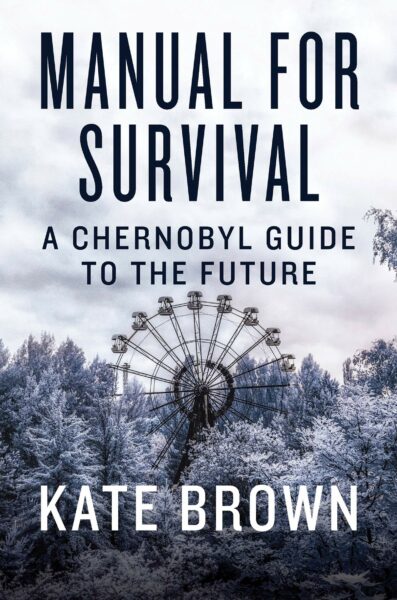

A Review of Kate Brown’s Manual for Survival: A Chernobyl Guide to the Future

By Ansar Fayyazuddin & M. V. Ramana

Volume 23, number 2, A People’s Green New Deal

A version of this review is co-published in Against the Current.

On April 26, 1986, one of the reactors at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in Ukraine exploded, scattering highly radioactive materials into the surroundings. More radioactive effluent was expelled by the fire ignited by the explosion. Swept by the wind, the fallout was scattered over much of Europe and beyond. In fact, the disaster came to international attention partly as a result of radioactive rain falling in faraway Sweden, only two days after the explosion. To date, thousands of square kilometers in Ukraine and Belarus remain closed to human habitation because of high radiation levels in what Soviet authorities deemed the Zone of Alienation.

This was all inconceivable to officials in the nuclear industry. In 1983, a Soviet nuclear specialist wrote in the Bulletin of the International Atomic Energy Agency, “a serious loss of coolant accident is practically impossible … The safety of nuclear power plants in the Soviet Union is assured by a very wide spectrum of measures.” The irreconcilability of experience and professional expert testimony has been a signature motif of the Chernobyl disaster.

This was all inconceivable to officials in the nuclear industry. In 1983, a Soviet nuclear specialist wrote in the Bulletin of the International Atomic Energy Agency, “a serious loss of coolant accident is practically impossible … The safety of nuclear power plants in the Soviet Union is assured by a very wide spectrum of measures.” The irreconcilability of experience and professional expert testimony has been a signature motif of the Chernobyl disaster.

Kate Brown’s Manual for Survival: A Chernobyl Guide to the Future lays bare the toll of the 1986 Chernobyl disaster from the perspective of the people who experienced it. Brown’s book is distinguished from other works on Chernobyl by years of archival and on-the-ground field research, as well as extensive firsthand oral history. It is the confluence of the right person for the subject approaching it at the right time. Kate Brown is a careful historian, with deep knowledge of the local culture and significant previous engagement on the effects of low-level radiation (her important book Plutopia recounts the effects of radiation on the communities and environment around two plutonium plants). Her timing was good, too. She started researching in the middle of the last decade, just as many archives from the former Soviet Union started opening up their records of Chernobyl and some of the survivors of the disaster were still available to recount their experience. Brown’s writing style also makes for absorbing reading. Her human subjects are portrayed with empathy and warmth even when she disagrees with them, the landscape is vividly conceived, and the historical background always engaging and pertinent.

Manual for Survival is partly structured as a mystery: why do official accounts of this major disaster only record an absurdly small number of deaths and relatively minor long-term ill-effects? For decades, the Soviet state and many international bodies reported only thirty-one to fifty-four short-term fatalities and a few thousand thyroid cancers. Brown investigates the origin of these numbers and provides a fuller picture of the devastating consequences of the accident, many of which continue to unfold today. Her heroines and heroes—factory workers, doctors, some scientists and activists—are all, in their own ways, carrying out a science for the people, often at odds with officialdom. They don’t start off trying to carry out such science but are driven to it by virtue of living and working in contaminated regions and endeavoring to make sense of their own experience and observations. As elsewhere, citizens in Belarus and Ukraine had to take matters into their own hands and learn to measure radiation doses and mitigate contamination. Brown’s portraits bring to life what cold numbers never can. One is reminded of psychologist Robert Jay Lifton’s pithy observation: “statistics don’t bleed.”

The official denial of the consequences of the Chernobyl disaster follows a familiar playbook. The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were followed by a blackout of information about the resulting deaths and, especially, the impact of radiation exposure. Similarly, the adverse health effects of atomic bomb tests and accidents at nuclear facilities were kept secret by governments; any revelations were treated as public relations problems rather than as opportunities to address the public health disaster they actually were.

Surprisingly, far from using the Chernobyl disaster in anti-Soviet rhetoric, US government agencies accepted the claims of minimal disruption of the ecology and effects on human health. This strange congruence between the Cold War rivals was, Brown argues, due to their mutual interest in preserving the legitimacy of nuclear power as a safe energy source. Timing also played a part. During the 1990s, when Chernobyl’s impacts were being debated, many Western countries, including the US, were being sued by their citizens for exposing them to radiation from atomic weapon tests.

Manual for Survival documents the various devices used to minimize the health toll from Chernobyl. One was to allow a very small number of conditions, specifically cancers, as the only admissible signatures of harmful radiation. A second was to use unwarranted extrapolations from earlier studies (e.g., the Hiroshima Lifespan Study) to Chernobyl. A third was to lowball the radiation dose people were exposed to, and then argue that any observed health effects could not be due to such small doses. A fourth was to define safe levels by fiat and declare that exposures below these levels could not cause health impacts.

In addition, Manual for Survival records one role that scientists sometimes play in undermining struggles for environmental justice, in this case, abusing their status as experts by denying negative health consequences of “low” levels of radiation, delegitimizing and undermining the lived experience of the affected population. This role is by no means specific to radiation debates. Brown situates Chernobyl in this long history of scientists deployed by corporations and governments to discredit popular environmental and public health movements.

Unsurprisingly, Brown’s questioning of the legitimacy of the technocratic whitewashing of the real impact of Chernobyl has been criticized. Some reviewers have attacked her by counterposing her claims with those made by the kinds of “experts” whose work stands exposed by the history Brown uncovers. Underlying these attacks and the associated debate over the health impacts of low-level radiation is the future of the nuclear industry, with billions of dollars at stake. Brown does not pretend to be observing from the proverbial disinterested academic ivory tower and argues for her point of view rigorously.

The book’s subtitle, A Chernobyl Guide to the Future, suggests that this is not history for history’s sake but a message for us now when nuclear power is being aggressively promoted as a solution to climate change. By bringing home the lessons of Chernobyl, Brown gives a glimpse of a possible future if nuclear power is pursued. If we absorb this history, the seductions of nuclear power will no longer have a hold on us. We thus have in our hands history as redemption—the unacknowledged victims of Chernobyl finally have a voice; like Hamlet’s father, their ghosts flicker through these pages demanding acknowledgment and redress for the injustice done to them—and history as prophecy, what Chernobyl portends for the future if we pursue nuclear power: a proliferation of nuclear ecological disasters.

Manual for Survival: A Chernobyl Guide to the Future

Kate Brown

W. W. Norton & Company

2019

432 pages

About the Authors

Ansar Fayyazuddin, PhD is a theoretical physicist.

M. V. Ramana, PhD is the Simons Chair in Disarmament, Global and Human Security at the School of Public Policy and Global Affairs, University of British Columbia and the author of The Power of Promise: Examining Nuclear Energy in India (Penguin Books, 2012) and co-editor of Prisoners of the Nuclear Dream (Orient Longman, 2003). He is the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship and a Leo Szilard Award from the American Physical Society. He can be found on Facebook.