Fighting Back with Science and Technology for the People in the Philippines

By Sero Toriano Parel

Volume 23, number 1, Science Under Occupation

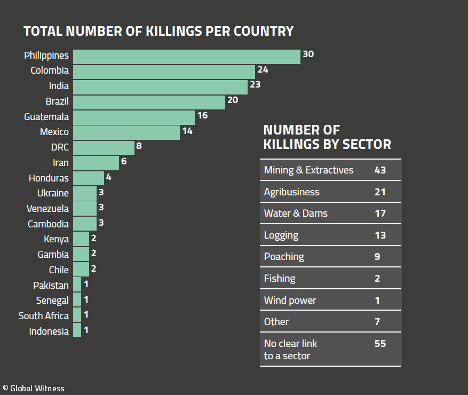

One cloudy, humid day in July 2018, I participated in a climate demonstration in front of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) in the heart of Metro Manila, Philippines. As part of an internship with Advocates of Science and Technology for the People (AGHAM), I joined progressive science and environmental organizations calling out the Philippine government’s complicity in allowing deregulated environmental plunder by local and foreign corporations, such as private resorts and casinos.1 I held a hand-painted blue placard with the call “Give jobs! Reopen Boracay!” while others wielded signs saying “Boracay is not for sale!” or “Stop militarization in Boracay!” Although, according to the rights watchdog Global Witness, the Philippines is now the deadliest country for environmental activists, these activists stood their ground.2

A small island located in the central part of the Philippine archipelago, Boracay was targeted to be the centerpiece of Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte’s environmental policy, according to news releases from several government agencies.3 Since his inauguration in June 2016, Duterte has made international headlines about his regime’s war on drugs, which has been rife with extrajudicial killings. While the Philippine National Police (PNP) reports that 5,552 people were killed under the “national crusade against illegal drugs” between 2016 and 2019, reports from independent sources conflict with these numbers.4 The PNP also reports at least 23,518 other drug-related killings committed by unknown armed persons during most of this period.5 Organizations such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, as well as local rights groups and the media, claim that these unknown armed persons in many cases have a direct link to the police, either having been hired by the police or being themselves police officers in disguise.6

Boracay has also been making news more locally. The Philippine DENR, Department of Tourism, and Department of the Interior and Local Government have called for the rehabilitation of the island, which they call a “cesspool” of water and land pollution.7 Boracay is a tourist hotspot, which to science advocacy groups like AGHAM suggests that Duterte was mostly motivated by profit interests disguised as environmental rehabilitation.8

In a press release, Leon Dulce, National Coordinator of the environmental group KALIKASAN, provided the following statement linking the closure of the island to worsening joblessness:

“This unjust closure has caused hunger and joblessness for over 24,000 workers and their families. The closure of Boracay seemed like the proverbial ‘fault-of-some is the fault-of-all,’ on top of the sheer military terror the Duterte government has imposed upon the residents. The sanctions on long-time and big-time environmental violators need not be borne by all the workers and residents of Boracay. In the first place, the lack of jobs and industry in the mainland is the reason why the workers flock to the island and contribute to its congestion.”9

Environmental destruction, unemployment, and the lack of national industry were running themes in my AGHAM internship, as well as science activism and progressive, revolutionary struggle. AGHAM, Tagalog for “science,” is a grassroots organization of scientist-activists advancing the science and technology sector to contribute to genuine national development.

During my time with AGHAM, I learned how the roles of science and technology workers were crucial for Philippine society: they are the lifeblood of research and innovation, play key roles in industrialization, and solve basic scientific problems for society.

What can the world learn from a geographically small but heavily populated country where the state of STEM is backward and stunted, but where progressive science advocacy and activism thrive?

Economy, Science, and Technology

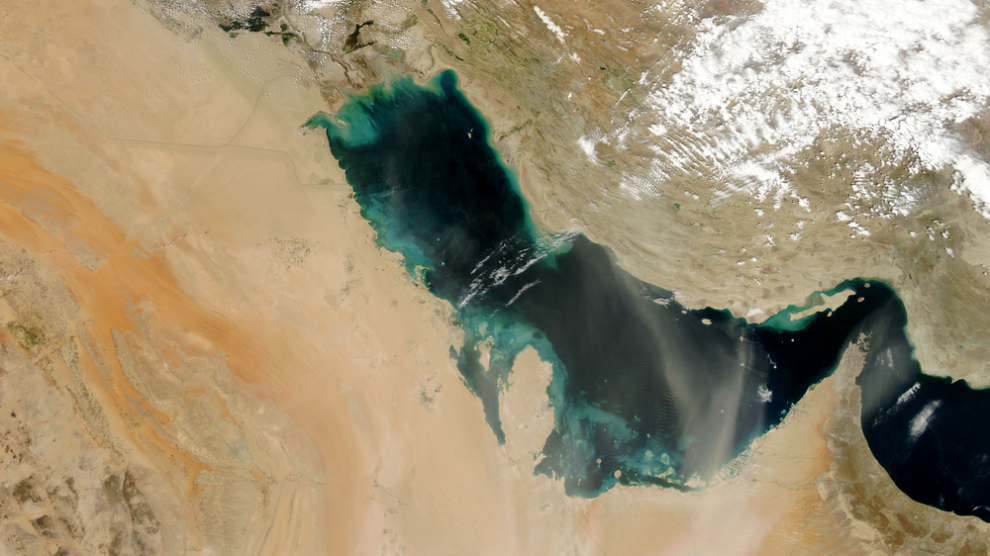

In understanding the state of STEM in the Philippines, it is fundamental to grasp the political, economic, and national development underpinnings of the country. Home to over one hundred million people, the Philippines is an archipelago of more than seven thousand islands in Southeast Asia. The islands are rich in natural resources, but the people remain poor. The country is strongly agricultural with an overwhelming foreign capitalist presence, leaving the Philippines with no national industry to call its own, according to Dr. Edberto Villegas, author of Studies in Philippine Political Economy (1983) and retired Professor in Development Studies at University of the Philippines, Manila. In addition, foreign corporations, including some based in the US, avail themselves of cheap raw materials (minerals, oil, and natural gas), a cheap labor force, a dumping ground for surplus US products, and billions of dollars in investments. In 2017 alone, the Office of the US Trade Representative reported $7.1 billion in foreign direct investment in the Philippines, largely in the form of manufacturing, wholesale trade, and professional, scientific, and technical services.10 In short, the character of the society is semi-feudal and semi-colonial, beholden to US imperialism.11

Widespread poverty and unemployment afflict the Filipino people. The daily minimum wage is less than $11 (US) per day in the National Capital Region.12 In 2017, 4.7 million people were unemployed and an additional 6.5 million were underemployed.13 The contribution of industry and manufacturing to the gross domestic product has been declining and has been surpassed by the service industry since the 1980s.

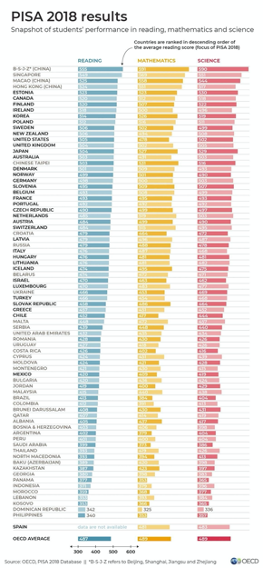

Science and mathematics education in the Philippines is weak, and the quality and accessibility of education in general is poor.14 According to the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Filipino fifteen-year-old students ranked the second worst in science and mathematics education (and the lowest in reading) out of the seventy-nine PISA-participating countries (Figure 1).15 Only 22 percent of Filipino students achieved a minimum level of proficiency in science—and 19 percent in math. Less than 1 percent of students attained the highest levels of proficiency in science and math. Moreover, government spending per student in the Philippines ranked the lowest, 90 percent lower than the OECD average. The Philippine educational system is oriented toward producing skilled labor for extractive and exploitative markets, and not toward the country’s domestic needs. For example, the government’s Technical and Vocational Skills Authority reports that land transportation, processed food and beverages, and business processing outsourcing are “priority sectors” with “critical skills shortages.”16

Of the Filipino youth who make it to the twelfth grade, very few become full-time researchers, less than 0.02 percent. Research and development (R&D) is important in increasing economic growth and productivity, but R&D expenditures compose only 0.1 percent of the GDP.17 In contrast, the 2020 budget submitted to Congress clearly prioritizes infrastructure for big business and the military over economic and social services that would benefit the majority of Filipinos.18

Filipino STEM workers are subject to job insecurity, low wages, and contractualization.19 Contractualization comes in such forms as job orders, contract of service employment, and project-based hiring that make scientists susceptible to becoming victims of state neglect. Even scientists working in government agencies lack social protection from the government itself, and they receive no compensation or hazard pay for dangerous jobs.20 Taken together, the state of STEM and labor laws in the Philippines is backward and stunted.

What then is left for Filipino scientists, given these political and economic conditions?

Labor Export of Scientists

With the lack of both jobs and national industry, many Filipino scientists are forced to migrate to find science jobs. The Department of Science and Technology’s Science Education Institute’s (DOST-SEI) last report, in 2015, found an alerting exodus of Filipino scientists from the archipelago: the number of STEM workers who migrated from the country to work abroad increased from 40,000 in 1990 to 113,000 in 2010.21 Most move to Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, or the US.22 Every day, six thousand Filipinos leave their country in the hope of finding better opportunities abroad.23

In response to the Philippine brain drain, President Duterte signed the Balik Scientist Program into law in June 2018, right in the middle of my exposure trip with AGHAM.24 The program “encourages Filipino scientists, technologists, and experts to return to the country and share their expertise in order to promote scientific, agro-industrial, and economic development”.25

Attacks on Science and Environmental Defenders

Many Filipino scientists have voiced their concerns about social issues and the state of STEM. Leonard Co, arguably the foremost ethnobotanist of his time in the Philippines, saw firsthand the environmental plunder and destruction in his fieldwork, and consequently devoted his work to environmental activism. In 2010, Co and his team were targeted and slain by the Armed Forces of the Philippines under the false suspicion of being involved with the Communist Party of the Philippines’ (CPP) New People’s Army (NPA).26

A more recent example is Brandon Lee, the first US citizen to be caught in the crosshairs of an extra-judicial assassination attempt by the Duterte regime.27 Lee, a Chinese-American born and raised in San Francisco, was always deeply integrated in the local Filipino community. After going on an exposure trip to the Philippines, Lee decided to move there, dedicating his life to the fight for indigenous and land rights as a community activist and paralegal. Brandon was harassed and surveilled by the Philippine military for years, and then shot multiple times in the face and back outside his home on August 6, 2019, just days after being repeatedly visited by members of the 54th Infantry Battalion of the Philippine Army. Brandon suffered a coma, and his friends, family, and allied organizations such as the International Coalition for Human Rights in the Philippines facilitated his safe return to San Francisco on October 28, 2019.

Unfortunately, Co and Lee’s cases are far from unusual. As early as 1984, the state of human and environmental rights in the Philippines have been in such crisis that even the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) conducted a fact-finding mission to investigate human rights violations on health personnel under the then-dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos.28 Other politically motivated cases since then are the killing of environmentalist Gerry Ortega in 2011, the political imprisonment of physicist Kim Gargar in 2013, the slaying of engineer Delle Salvador in 2014, and the red-baiting of AGHAM’s Secretary General Feny Cosico.29 To this day, the Philippines remain the deadliest country in the world for environmental and human rights defenders, followed by countries such as Brazil, Guatemala, and Honduras, where there are also ongoing movements for liberation (Figure 2).30

STEM for the People and International Solidarity

Despite the dire situation for scientists, I found that mass organizations like AGHAM incrementally advance the path for change in STEM. These were just a few lessons I learned from my experience with this science advocacy organization:

- Allocate adequate resources for programs developing the country’s science and technology infrastructure to correct its historical and prevailing neglect.

- Develop and propagate comprehensive curricula in the basic sciences, engineering, modern agricultural techniques and management.

- Ensure an adequate supply of skilled, competent, and progressive human resources geared towards domestic needs and priorities, rather than those of foreign corporations and to brain drain.

Inspired by AGHAM and its principles, other Filipino scientists in the US and I have built an initiative called the Association for Filipino Scientists in America (AFSA). AFSA provides a network that seeks to utilize its members’ various expertise to support Filipino communities.

My experience with science activism in the Philippines has taught me that there will only be full meaning to the product of my scientific and intellectual endeavors when they enrich the lives of broad masses of people, not just the few who impose their rule. In the ongoing struggle to diversify and modernize our economy, Filipinos call on STEM workers of all origins to provide support on the basis of international solidarity.

Since late 2018 Boracay has been reopened, but the rehabilitation has resulted in the rampant demolition of the community and the displacement of many fisherfolks, while government agencies allowed the entry of big corporations. The fight for Boracay and the rest of my experience with AGHAM showed me that STEM for the Filipino people means the active promotion of pro-people development, national industrialization, genuine agrarian reform, and a united front with other progressive sectors.

These current challenges have led to AFSA’s immediate calls to action on climate change: push for genuine changes in government policies to protect the environment, not degradation through the government’s support for large-scale mining, logging, and developmental schemes. End the destruction of ecosystems that will displace indigenous peoples from their ancestral lands! Call for policies that will truly protect the environment in the Philippines and other countries where there is continued extraction of resources by the local elite and foreign countries who are the perpetrators of human rights violations!31

About the Author

Sero Toriano Parel (they/siya/Mx.) is a founding member of the Association for Filipino Scientists in America, a representative of the New Jersey chapter of the International Coalition for Human Rights in the Philippines, and a PhD student in neuroscience at Princeton University. Sero is from Quezon City, Philippines, by way of Louisville, Kentucky. Forced to migrate and brought up working class, they write from their lens as a queer, non-binary, proletarian internationalist Filipinx. They are broadly interested in resilience and revolution, from the brain to oppressed and exploited peoples. Sero can be reached at parel@princeton.edu or twitter.com/mx_sero.

References

- Leon Dulce, “Democratic Space | Does Duterte intend to clean up Boracay with bullets and bombs?” Bulatlat, April 29, 2018; Tyra Aquino, “No clear plan for Boracay rehab, experts say,” Bulatlat, June 27, 2018; Marya Salamat, “Big-ticket projects could ease out Pinoy biz, jobs in Boracay ‘rehab’ – Bayan Muna,” Bulatlat, April 11, 2018.

- Leon Dulce, “The Dangers Of Environmental Activism In The Philippines,” Interview by Scott Simon, NPR, August 3, 2019.

- Catherine Teves, “Environmental protection remains Duterte admin’s top priority,” Philippine News Agency, Republic of the Philippines, July 22, 2019; “Palace: Boracay clean-up a top priority of the President,” Presidential Communications Operations Office, Republic of the Philippines, April 2, 2018; “Gov’t. agencies unfold plans to #SaveBoracay,” Kagawaran ng Turismo, Republic of the Philippines, April 18, 2018.

- Karapatan Alliance Philippines, “Karapatan Monitor, April-June 2019,” Report, September 10, 2019.

- Rambo Talabong, “At least 33 killed daily in the Philippines since Duterte assumed office,” Rappler, December 17, 2018.

- Human Rights Watch, ‘They just kill’. Ongoing extrajudicial executions and other violations in the Philippines’ ‘war on drugs’. July 8, 2019; Human Rights Watch, License to Kill: Philippine police killings in Duterte’s “War on Drugs,” 2 March 2017; Amnesty International, If you are poor you are killed: Extrajudicial executions in the Philippines’ “War on Drugs,” January 2017: 37-39.

- “No clear plan for Boracay rehab, experts say,” Bulatlat, June 27, 2018.

- AGHAM, “DENR partnerships for rehab efforts to benefit investors, not the people,” Press Release, August 8, 2018.

- KALIKASAN, “No rehab plan, no reason to keep Boracay fully closed,” Press Release, July 9, 2018.

- “Philippines,” Office of the United States Trade Representative, Executive Office of the President, accessed March 5, 2020.

- Jose Maria Sison, “The New Democratic Revolution Through Protracted People’s War,” Lecture, Forum for Liberation Theology, Centre for Liberation Theologies, Faculty of Theology and Religious Studies Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium, May 15, 2014; Jose Maria Sison, “Ang Imperyalismong US at Paglaban ng Sambayanang Pilipino,” Talumpati sa May Pag-Asa, Asamblea ng Kabataang Anti-Imperyalista, July 4, 2014.

- Ibon Foundation, “Praymer: Nakaambang pagsabog ng krisis sa ilalim ni Duterte,” January 2019.

- Ibon Foundation, “Praymer.”

- Hyacinth Tagupa, “What Happened to Our Basic Education?” Inquirer, December 6, 2019; Darryl John Esguerra, “Palace takes ‘constructive view’ of PH dismal performance in math, science, reading,” Inquirer, December 5, 2019.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, “Philippines – Country Note – PISA 2018 Results,” Programme for International Student Assessment, 2019.

- Republic of the Philippines Technical Education and Skills Development Authority, “Investing in the 21st Century Skilled Filipino Workforce: The National Technical Education and Skills Development Plan, 2018 – 2022,” Taguig City, 2018.

- Institute for Statistics, “Philippines,” UNESCO, 2016.

- The Department of the Interior and Local Government and the Philippine National Police is seeing a 6.2 percent increase from 2019, and the Department of National Defense a 1.3 percent increase.

- Feny Cosico, “An appeal for more gov’t support for S&T,” Inquirer, July 6, 2016.

- Ghio Ong, Helen Flores, “Pagasa gives up hope for missing member,” Philippine Star, December 12, 2013; Pia Ranada, “4 killed in Nueva Vizcaya plane crash,” Rappler, April 29, 2014.

- Science Education Institute, “DOST-SEI study: PH S&T workers double in 20 years,” Department of Science and Technology, Republic of the Philippines, May 4, 2015.

- Science Education Institute, “DOST-SEI study: PH S&T workers double.”

- Ibon Foundation, “Praymer: Nakaambang pagsabog ng krisis sa ilalim ni Duterte,” January 2019; “Duterte’s Attacks on Filipino Migrants Denounced During Migrante International’s Pre-SONA Event ‘SUMA 2019: The Cost Of Duterte’s Labour Export Program,'” Migrante International, July 16, 2019.

- Jon Viktor D. Cabuenas, “Duterte signs Balik Scientist Program into law,” GMA News, June 24, 2018; Dennis Normile, “Philippines Plans Research Revival,” Science 322, 5907 (2008): 1459; Andrew Silver, “Philippines sweetens deal for scientists who return home,” Nature 559, (2018): 453-454.

- Commission on Filipinos Overseas, “Balik Scientist – BaLinkBayaan Overseas Filipinos’ One Stop Online Portal for Diaspora Engagement,” Office of the President of the Philippines, Republic of the Philippines, January 25, 2020.

- Jesse Edep, “Scientists: Army’s bullets killed top Filipino botanist Leonard Co,” GMA News, December 8, 2010.

- Jeantelle Laberinto, “Human rights advocate shot in Philippines returns to SF,” 48hills.org, San Francisco Progressive Media Center, October 28, 2019.

- Eric Stover, “Fact-Finding Mission Visits Philippines,” Science 223 (1984): 1066.

- Ronalyn V. Olea, “Justice remains elusive for slain journalist, environmentalist Gerry Ortega,” Bulatlat, January 25, 2012; Marya Salamat, “Freed on bail: Kim Gargar describes life in jail as teacher, scientist, political detainee,” Bulatlat, August 11, 2014; Dee Ayroso, “Development worker killed in Abra encounter,” Bulatlat, September 9, 2014; SnT Say No to Tyranny, “Scientists and Technologists #StandUp4HumanRights #2018,” Press Release, December 10, 2018.

- Global Witness, “Enemies of the State?” July 2019.

- Sero Toriano Parel and Carla Bertulfo, “Filipino scientists call for prompt action on climate change,” The Fil Am (January 2020): 18-20.