Tough on Institutions, not Individuals: Resisting Militarism in Engineering Schools

By Anonymous

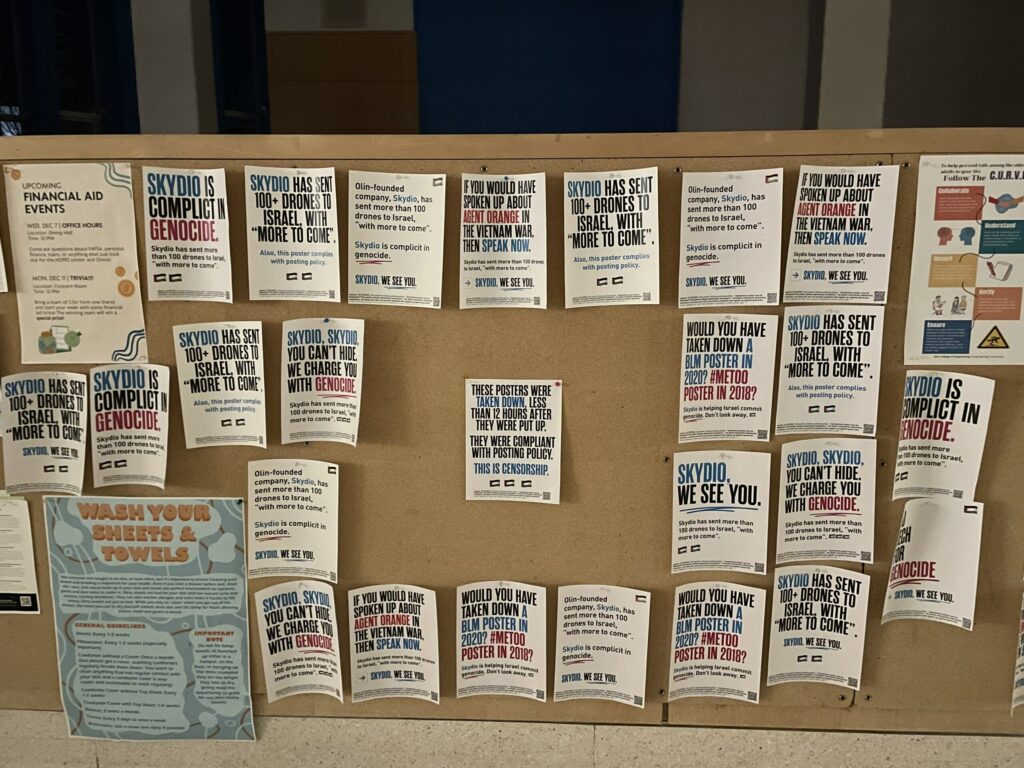

Late one night last December, I found myself walking across campus with a stack of paper in hand, carefully avoiding eye contact with the classmates who were tinkering with final projects and surreptitiously taping posters to bulletin boards whenever the coast was clear. All told, my fellow organizers and I put up several hundred posters broadcasting messages like “Skydio has sent 100 drones to Israel, with more to come,” “Olin-founded Skydio is complicit in genocide,” and “Skydio, we see you.”

The scale and pace of the genocide in Gaza is accelerated by the direct and indirect contributions of American universities. From the billions granted annually by the Department of Defense to research labs, to elaborate recruiting events designed to lock students into the “college-to-war-machine” pipeline, to capstone projects providing student labor to weapons manufacturers, engineering schools are a critical piece of the military-industrial complex.1 My school, Olin College of Engineering, often partners with companies profiting from the genocide like Raytheon, Boeing, and Ford. Our campaign focused specifically on Skydio, a drone manufacturer founded by Olin alumni that regularly recruits at Olin and employs many Olin students.

As an engineering student, I’ve noticed that debate among engineers often focuses on whether working at weapons companies is ethical. This kind of conversation individualizes responsibility and places it onto students, distracting from the many ways our universities are complicit in the war machine. It also plays into a common argument made by university administrators: that protesting military contractors is disrespectful to other students’ career choices.

In organizing our campaign for Olin to cut ties with Skydio, we learned that antimilitarist engineers must explicitly shift our target from individuals to institutions, and combine our activism with critiques of systemic forces like student debt that push fellow students into lucrative military contractor jobs.

Individualization of Responsibility

Under neoliberalism, the individual is held responsible for making “ethical” choices to fix societal issues, instead of directing attention toward the real institutional causes behind these issues, like corporations or governments. Michael Maniates, critiquing the mainstream environmental movement’s tendency to focus on small-scale consumer choices, named this phenomenon the “individualization of responsibility.”2 Obsession over personal choice can “resemble the foundations of meaningful social action,” but does not promote change “in any real and lasting way that might alter institutional arrangements.”3 Furthermore, individualization means that “there is little room to ponder institutions, the nature and exercise of political power, or ways of collectively changing the distribution of power and influence in society—to, in other words, ‘think institutionally.’”4 By focusing on individual ethics, institutions evade critique; the only levers of power that appear accessible are individual-scale choices, such as consumer purchases—or, for students entering the workforce, job choices.

For engineering students, the proliferation of job boards and fellowships promising careers with a positive impact has popularized the idea that engineers should make “ethical” career choices, which has in turn intensified debate over whether working in harmful industries is morally acceptable. Yet the incessant focus on whether an individual’s career can be made “moral” prevents a broader analysis of, and therefore collective resistance to, the ties between universities and the military-industrial complex. Individualization is compounded in engineering schools, where a “culture of disengagement” renders students increasingly depoliticized over the course of their studies.5 Nontechnical fields are considered to hold little value, so engineers often misperceive social change as the outcome of technological advancements, rather than a result of power relations. When one’s value to employers lies in the ability to build things to meet technical specifications, and when years of intense education are dedicated just to refine this ability, it follows that engineers would see their primary lever for change as a simple refusal to personally spend their own time building weapons.

At Olin, I’ve seen this individualization play out firsthand. Objections to military-sponsored research are often met with the dismissive response that “no one is forcing you to work there.” Students fundraising for clubs have told me they would never personally work for a weapons manufacturer, but would accept funding from military contractors in exchange for running a recruitment event. Avoiding the appearance of personal complicity is considered more important than challenging institutional relationships. We only seem to ask, “is it okay to work for Raytheon?”, instead of “why does our college partner with Raytheon at all?”

At a career fair a few years ago, a group of students put up memes criticizing students for working at military contractors (one showed a person reading a book titled “Engineering Ethics”, with the caption “Oliners working for defense companies”). The memes provoked a strong backlash from many students, with one upper-level student sending an all-students email accusing the memes of “[shaming] people for making a personal decision”. After the backlash, a friend who had been involved in the postering said that while they still stood by the sentiment, they weren’t sure they would do the action again: “the intent was to call out defense contractors, but we called out students in a way that definitely emotionally clashed with people”. The actual intended object of critique, Olin College and their choice to bring military contractors to career fairs, became lost in a debate about respecting other students.

“Skydio, We See You”

In November, a Politico article revealed that Skydio had sent hundreds of short-range reconnaissance drones to the Israeli military in the weeks following October 7.6 Angry that a company closely tied to our school would so willingly participate in genocide, a couple of us set out to anonymously poster the school in agitprop, hoping that the posters would make their way to Olin alumni at Skydio.

Instead, our posters were gone before breakfast.7 Olin’s dean then sent out an all-school invitation for a community conversation where students were encouraged to “listen as well as speak”. We knew the admin’s history of extinguishing activism with meetings that go nowhere, and were worried about maintaining anonymity, but we wanted to hear why they removed our posters. So we went.

We weren’t surprised when the administrators at the meeting accused the posters of being antisemitic—this is a common tactic to silence Palestinian activism.8 However, they also claimed that by opposing weapons manufacturers, we were shaming other students’ career choices.

We learned that Olin’s head of career services, who advises students on job applications and organizes career fairs, had taken down the posters. She explained that working at controversial companies was solely a personal decision: “at my previous job, I didn’t necessarily support students going to Goldman Sachs. But it was my job as a career advisor to help students who wanted to go there.”9 Her job, as she put it, was to defend other students’ right to choose employment, and our posters were infringing on their freedom of career choice.

According to this administrator, criticizing Skydio belied our privilege. Antimilitarism “impacts students who struggle to find work [and] vocalization of telling others where they should work is a privilege.” In this argument, only wealthy students who can choose an “ethical” (and implicitly low-paying) job have the luxury of applying moral standards to companies. Putting up anti-Skydio posters was supposedly disrespectful to the low-income students who accept lucrative positions at weapons manufacturers to support themselves.

Our posters had not mentioned students at all. Yet to this administrator, by charging Skydio with complicity in genocide, we were shaming other students who might want to work there. Her sleight of hand—that critiquing militarism at Olin is inherently a critique of individual students—redirected the conversation from atrocities committed with Skydio drones, to respecting individual students’ choices.

Antimilitarist dissent at other schools has been met with similar individualization tactics. In response to an article detailing universities’ extensive Department of Defense lobbying efforts, MIT’s former Vice President for Research Maria Zuber argued that “if there are students who have a feeling that they don’t want to work on defense-related issues, they certainly don’t have to.”10 Similarly, after the Progressive Student Alliance at Northeastern protested a Raytheon recruitment event, Andrea Felder, a recruiter for Raytheon subsidiary Collins Aerospace, used the same justification: it is a “personal decision of the employees […] to be associated with the company”, and “everybody has their own personal beliefs and they’re welcome to follow them.”11

How can administrators possibly defend the companies making weapons that massacre more Palestinians each week than our entire student body population? They can’t. Instead, they must wield class privilege and freedom of career choice as distractions, to avoid engaging with the terrible reality: that our college’s most successful alumni company is powering a genocide.

Tough on Institutions, But Soft on People

We debated how to respond. On one hand, some in our group felt that nothing could really justify working for a genocide profiteer. As one organizer asked bluntly, “would being poor make it okay to be an assassin?” While we are all entitled to having our basic needs met, and those rights are currently tied to giving corporations our labor, there is no such thing as the “right to work at a weapons manufacturer without feeling guilty about it.” What’s more, American engineering students arguably have better job prospects than almost any other demographic in the world, and even more so at a top school like Olin.12 Were we really so pressed for career opportunities that we had no choice but to build weapons?

But we knew fixating on individual culpability would only fuel the argument that we were shaming students for their career choices. If other students felt shamed by our organizing, student opinion could turn against us as it did with the career fair memes a few years prior. We’d seen how shame turned potential supporters away, rather than bringing them in.

We also recognized that whether any given individual takes a job at a weapons manufacturer doesn’t really matter. What matters is the vast web of relationships between the academy and the military-industrial complex that results in unimaginable death and destruction abroad.

We needed to be tough on institutions, but soft on people.13 Whatever we personally believed, we knew we could not fall into the trap of individualized ethics. Focusing on individual ethics would only distract from the ways Olin, the institution, was complicit. We had to keep the focus on Skydio.

What was initially an impulse decision to poster quickly morphed into a much larger campaign. We postered the school every night for two weeks straight, while ensuring posters narrowly criticized Olin and Skydio’s connections to the genocide, without mentioning students. We distributed a petition to alumni pledging to withhold donations from our college until it cut ties with genocide profiteers—thus explicitly identifying Olin and Skydio as the focus of our activism. And we sent a campus-wide email, stating that “Skydio is complicit in genocide. We refuse to let [this fact] be misconstrued as criticism of individual career choices.”

“Batshit Jobs”

It is, however, indisputable that college is very, very expensive, and weapons companies pay well. As engineers, we are often assured that our skills are in high demand—but we are never told by whom. We are never told that industries like weapons, oil, and pharma have invested heavily in a STEM pipeline that captures students—particularly immigrant and lower middle-class students—with the assurance of a stable career.14 Our “employability” is only proof that powerful industries need technical labor.

To fully confront the accusation that antimilitarist activism is class-privileged, we turned to Bue Rübner Hansen’s concept of “batshit jobs”, describing fossil fuel jobs that destroy workers’ bodies and environments, but are taken by people who are not in the position to change their line of work.15 Hansen calls this paradox “a kind of systemic madness”: “to call this work mad [is to] point out that a crazy contradiction arises when making a living is also a part of unmaking life on many scales […]. Workers have an interest in habitable environments, but are caught in a maddening contradiction, asked by their employers to destroy the conditions of life in order to make a living. We are habituated to think of this as normal, even rational, but it’s time to say openly that it is madness, and to start from there.”

As we wrote in an op-ed for our school newspaper, jobs building weapons are “batshit.”16 No one has the right to kill people or the planet for a living, but at the same time, no one should have to. If college is so expensive that students are forced to build weapons to escape student debt, then make college less expensive! The billions our government spends each year propping up weapons manufacturers is money that could have subsidized tuition or canceled student debt.

Deathmaking industries benefit from student precarity. We have to critique the ever-increasing tuition which funnels students into these industries, making career “choice” not much of a choice at all. In the same way that the slogan “money for jobs and education, not for war and occupation!” combines a critique of empire abroad with demands to fix our crumbling social safety net at home, student activism must combine critiques of university-military partnerships with demands for an affordable education.

It can be easy to feel dispirited at the enormity of the task ahead of us. Harsh repression of calls for divestment has revealed not only a staunch support for Israel, but universities’ overwhelming reliance on the war machine for research funding and jobs. We have to remember that we have won divestment campaigns before, and we can do it again. Half a century ago, determined student and faculty opposition to the Vietnam War forced many universities to sever ties with the military-industrial complex.17 Engineering schools including Stanford, Cornell, and MIT divested on-campus labs conducting substantial weapons research.18 In the decades since, student organizers have won divestment from South African apartheid, genocide in Sudan, and tobacco and fossil fuel companies.19

Our universities do not have to help build killing machines, and our livelihoods do not have to be predicated on someone else’s suffering. But to build the antimilitarist movement we need, we cannot turn our anger on individuals caught in forces beyond their control. Our energy must tear down the institutions of empire—not each other.

Notes

-

- Michael T. Gibbons, “Universities Report Largest Growth in Federally Funded R&D Expenditures since FY 2011,” National Science Foundation, Higher Education Research and Development Survey, December 15, 2022, https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsf23303; In one senior capstone program at Olin, SCOPE, students work on a year-long engineering project for a corporate partner. Partners pay Olin for the work produced, while students are compensated with academic credit.

- Michael F. Maniates, “Individualization: Plant a Tree, Buy a Bike, Save the World?”, Global Environmental Politics 1, no. 3 (August 2001): 31-52, https://doi.org/10.1162/152638001316881395.

- Maniates, “Individualization,” 38.

- Maniates, “Individualization,” 33.

- Erin Cech, “Culture of Disengagement in Engineering Education?”, Science, Technology, & Human Values 39, no. 1 (January 2014): 42–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243913504305.

- Mohar Chatterjee, “Israel’s Appetite for High-tech Weapons Highlights a Biden Policy Gap,” Politico, November 25, 2023, https://www.politico.com/news/2023/11/25/israel-hamas-war-ai-weapons-00128550.

- Sazma Sarwar, “Olin Administration removes posters on Skydio’s ties to Israel,” The Wellesley News, February 21, 2024, https://thewellesleynews.com/18244/news-investigation/olin-administration-removes-posters-on-skydios-ties-to-israel/.

- Michael Young, “Weaponizing the Antisemitism Accusation,” Diwan, June 6, 2023, https://carnegieendowment.org/middle-east/diwan/2023/06/weaponizing-the-antisemitism-accusation?lang=en.

- These quotes are approximations based on notes taken by students present at the meeting.

- Austin Wright, “Universities Chase Defense Dollars,” Politico, August 13, 2014, https://www.politico.com/story/2014/08/university-research-defense-funding-109980.

- Katherine Mailly, “Progressive Student Alliance Protests Raytheon Recruitment Event on Campus,” The Huntington News, March 16, 2023, https://huntnewsnu.com/70939/campus/progressive-student-alliance-protests-raytheon-recruitment-event-on-campus/.

- “Olin College Tops New List of Colleges by Earnings,” Olin College, accessed Oct 8, 2024, https://www.olin.edu/articles/olin-college-tops-new-list-colleges-earnings.

- “Tough on institutions, but soft on people” is an organizing mantra I heard at JVP Hawaii’s panel discussion and screening of the film Israelism.

- Indigo Olivier, “US Universities are Pipelines to the Defense Industry. What Does that Say about Our Morals?”, The Guardian, August 18, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/aug/18/us-universities-are-pipelines-to-the-defense-industry-what-does-that-say-about-our-morals.

- Bue Rübner Hansen, “‘Batshit Jobs’ – No-One Should Have to Destroy the Planet to Make a Living,” openDemocracy, June 11, 2019, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/opendemocracyuk/batshit-jobs-no-one-should-have-to-destroy-the-planet-to-make-a-living/.

- Anonymous, “Not a Privilege But a Right,” Frankly Speaking, February 5, 2024, https://franklyspeakingnews.com/2024/02/not-a-privilege-but-a-right/.

- Barry Smart, “Military-Industrial Complexities, University Research and Neoliberal Economy,” Journal of Sociology 52, no. 3 (September 2016): 455-481, https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783316654258.

- David A. Wilson, “Consequential Controversies,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 502, no. 1 (March 1989): 40–57, https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716289502001004.

- Atif Ansar, Ben Caldecott, and James Tilbury, “Stranded assets and the fossil fuel divestment campaign: what does divestment mean for the valuation of fossil fuel assets?”,

- Stranded Assets Programme at the University of Oxford’s Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, October 2013, https://www.smithschool.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2022-03/SAP-divestment-report-final.pdf.