Even the Seas are Caged: Palestine’s Coastal Areas Under Occupation

By Lowell Iporac

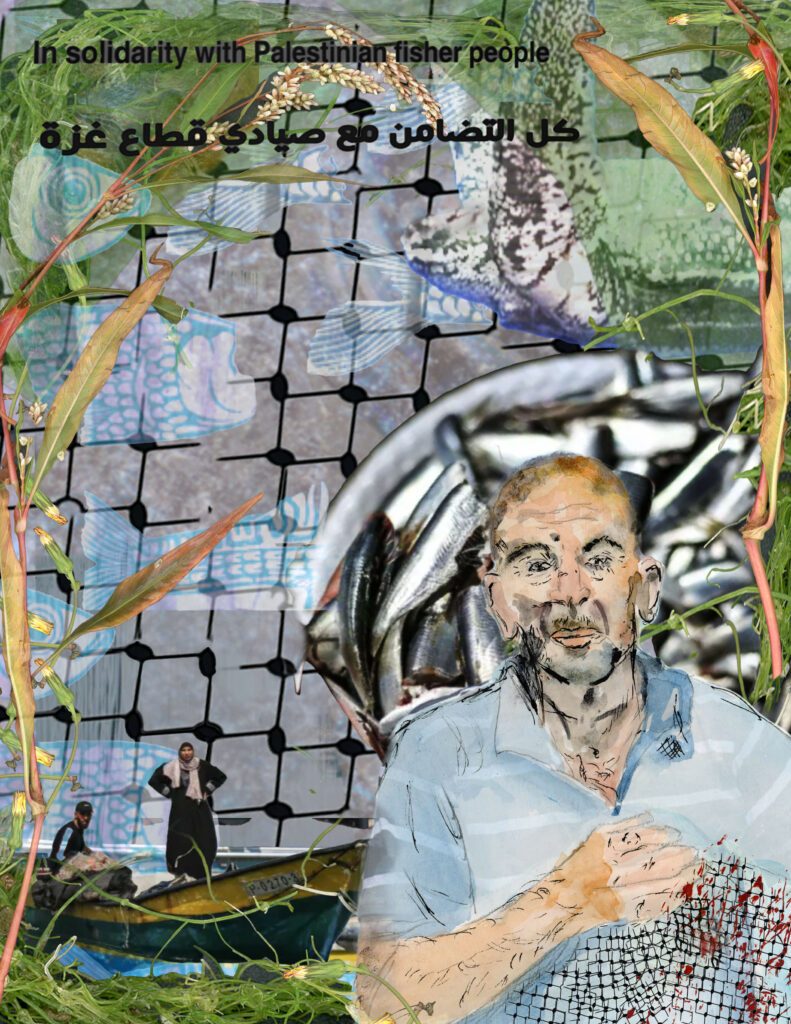

The Mediterranean Sea, next to the shorelines of Gaza, harbors marine life that sustains the local Indigenous Palestinians. The salty sea breeze and abundant fisheries breathe life into the coastal communities where Gazans would buy and sell seafood for subsistence for their families. The fishing harbor, where many of the fisherfolks’ boats were docked, also harbored many roosting migratory birds such as black-headed gulls and common terns. This intergenerational connection of Palestinians to the ocean was so deep-rooted that it was represented by the fishing net pattern on the Palestinian Keffiyeh. The Palestinian Keffiyeh, in response to the zionist occupation, developed into a symbol of Palestinian identity and resistance.

The coast of Gaza (and occupied Palestine as a whole) lies among the greater Levant region of the Mediterranean Sea Basin, which also includes Egypt, Lebanon, and Syria. Marine fauna crossing the Gaza strip include iconic species listed in the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), such as the globally vulnerable leatherback sea turtle, the endangered spinetail devil ray, and the vulnerable ocean sunfish, the largest living bonefish in the world. Many Palestinian fishers are small-boat, artisanal fishers that fish for subsistence and use seine nets to catch sardines, mackerel, tuna, and amberjack.1

Like the marine fauna that migrate along the Mediterranean, the fishing grounds of Palestinian fishers transcend political boundaries, often based on local practices that are passed down from generation to generation.2 Even today, the Gazan fisher community holds local ecological knowledge, such as marine faunal strandings, fishery migration patterns, and ecological significance of fishery species.3 However, because of the occupation, the ecological knowledge of the Gazan fishers also included Israeli militarization effects on marine life and their fellow fishers.

Severing Connection Between Fisher and Sea

Gaza currently covers 40 km of coastline, a mere 13 percent of the coastline that was once part of Palestine before the occupation.4 The amount of available fishing grounds for Gazan fishers is even more paltry. Under the 1993 Oslo accords, Gazan fishers were allowed to fish up to twenty nautical miles off the coast of Gaza. On the ground however, Gazans were left with only three to six nautical miles due to the blockade and aggressive militarization by the occupation, especially following the Second Intifada in 2000. The Israeli government has made the zone outside the allowable fishing area an involuntary no-take marine area that would prevent harvest of fisheries by Gazan fishers. Much of the fish species are found more in the deeper parts of the fishing grounds, which are larger in size and more abundant than in the shallow areas of the fishing grounds.5 The sardine market, which was once the most prominent of the fishery markets in Gaza, now had to rely on Israeli exports, which are more expensive to import.6

Gazan fishers venturing out to the militarized zone risk getting shot and abducted by Israel, including detainment and confiscation of fishing equipment and catches. In one confrontational incident in 2022, Gazan fishers faced live fire, abduction by the navy, and even raw sewage dumped on the fishing grounds.7 The violence of the Israeli navy also extends towards marine life, shooting and killing cetaceans (such as dolphins and baleen whales) that were mistaken for submarines, according to local Gazan fishers.8

Had there not been militarization of fishing grounds and an economic blockade of selling fish outside of Gaza, the fishing market of Gaza would have access beyond its borders and become much more competitively viable.9 The economic blockade of Gaza also prevented their boats from repairs or replacements. What was once a vibrant community next to an equally vibrant marine ecosystem, these conditions transformed Gaza’s fisheries into an impoverished economic sector, with 90 percent of Gaza’s fishers living below the poverty line.10

The austere conditions of poverty are driving overfishing in shallow fishing areas to the point of depletion, and can also affect endangered species as collateral damage. One species of ray, the spinetail devil ray, was fished extensively from an unusual event in late February of 2013, even with IUCN classifying this species as endangered. 500 of these rays were caught and killed to be sold to Gaza’s fishing markets for US$2 per kilogram, a low price compared to other seafood sold at US$7–12 per kilogram. Additionally, ray meat is not considered to be as good of quality as other seafood, according to Gazan fishers. The fishers however, revered this large catch event as “a gift from God”.11

Following this event, a team of scientists reached out to local fishers on the IUCN endangered status of the spinetail devil ray, to prevent further overfishing of this species by the locals. Most Gazan fishers were receptive to changing their habits, reflecting their long held respect for wildlife.12 The population dynamics of spinetail devil rays were largely unknown, but there was a major decline in the species abundance for the past thirty-eight years, representing three generational lengths of this ray species.13 These rays seem to migrate across the Mediterranean Sea in mid-January from the northeastern end (Turkey and the Greek Islands) to the southeastern end (Palestine, Egypt, and Syria), depending on changes in temperature. By following warmer water temperatures in Palestine, the waters off of Palestine may have been fruitful for mating.14 While it still isn’t clear as to why the rays moved closer to shore, the restricted fishing grounds, due to the zionist occupation creating poverty conditions for Gazan fishers, makes for this unusually opportunistic fishing event to occur.

The Resistance of Palestinian Fishers

Given the historical connections between Palestinians and the ocean, Palestinian fisher communities also have a history of resistance against the occupation of their grounds and livelihoods. Even after their displacement through the Nakba in 1948, Palestinian fishers that fled north to Lebanon would often return to their fishing grounds despite surveillance and aggression from Israel. Interactions between Palestine and Lebanon’s fishing communities form a sort of conditional solidarity, with both facing Israeli violence while also dealing with internal disputes between Lebanese and Palestinian fishers.15

Ironically, the Gazan fisher community wasn’t always this politicized. Even since 1993, Gazan fishers were fairly self-sufficient in their economic subsistence capacity, being able to support themselves and their families. It wasn’t until the 2007 imposition of the economic blockade on Gaza by Israel that Gazan fishers started feeling the brunt of economic hardship. Although there were NGO-based initiatives to provide aid to Gazans, those NGOs also undermine governments that do not align with western governmental interests (Gaza’s government was under Hamas leadership from 2007 onwards) while failing to combat the Israeli occupation or blockade.16

Two months before October 7, members of Gaza’s fishing community staged a sit-in following multiple attacks towards their fishing boats from the Israeli navy, including arrests and seizure of boats. On that day, around 200 fisherfolks attended the sit-in, including members of the Union of Agricultural Work Committees and the World Forum of Fisher Peoples standing in solidarity with Palestinian fishers.17 Their demand was to be able to “fish freely” and demand immediate intervention by the international community. Those demands weren’t met, as even to this year many of those fisherfolks continue to suffer and be killed by the occupation, including by starvation and military fire.18

Loss of Life, Loss of Knowledge

Knowledge and education of marine ecosystems for Palestinians are extremely limited, and are exacerbated by ecocide and knowledge cleansing ( “scholasticide” for short) brought as extensions of the genocide in Gaza. Despite a vibrant ecological and environmental science community in Palestine, that development is both overshadowed by the research and development scene of Israel, as well as demolition of entire research and education sites in Gaza. Indeed, many of the peer-reviewed articles in this piece had at least one author from the Islamic University of Gaza (IUG). Following October 7, the Islamic University of Gaza was effectively destroyed a few days later.19

Unfortunately for IUG, that incident has not been the first time that university was subjected to bombardment. From 1999-2008, IUG used to house a biological exhibition that housed many museum specimens of marine and terrestrial vertebrate fauna. Despite the vast, unique biodiversity collected in Palestine, many of these specimens were poorly maintained, owing to the poorly ventilated rooms and inconsistent labeling. When Israel bombed the science and engineering labs in IUG in 2008, all of those specimens, along with experimental animal rooms and other biological labs, perished into a “pile of rubble and molten iron.”20

The erasure of Palestinian history in coastal areas also included omission of historical backgrounds in occupied territory. One example was the development of Akhziv National Park (Arabic name: az-Zeeb) close to the border of Lebanon. Established in 1968 as a National Park, the archaeological history of the park from the Israel Nature Parks and Authority (INPA) mentions Roman and Hellenistic periods. One site within Akhziv included an “ancient fishing village” next to a former Club Med holiday site.21 The coastal area comprising Akhziv was also a former site of a Palestinian village (referred to by locals as “al-Zib”), whose population was violently displaced during the Nakba through murder and sexual violence. The narrative park signs however, omitted this information: English signs didn’t mention any Arab history, while Hebrew signs reduced Arab history to one sentence describing an elaborate Jewish community with a castle that was later reduced to a fishing village up until 1948.22

These examples of overt and covert erasure of ecological and historical knowledge in marine and coastal areas in occupied Palestine demonstrates the scholasticide of Palestinian connection to the seas. As research, conservation, and educational development continues in Israel’s academic scene, Palestinian educational institutions continue to erode—with lasting consequences of already suppressed scholarship by zionist forces.

Resisting Normalization of Genocide in Academia and Conservation

Many academics and professionals in the fields of ecology and environmental sciences see themselves as apolitical or as an “equitable” mediator between colonizers and colonized peoples. The marine sciences has its own history of being used for political ends, mainly as privatization of natural resources for capitalist gain.23 Often these extractive initiatives come at the expense of people from the Global South, who continue to bear the brunt of colonialism. The purist pursuit of knowledge is also tainted by scholasticide and colonial approaches to knowledge acquisition by academia; knowledge is extracted from people and places in the global south, with little to no reparations of whatever injustice or phenomenon is studied through an academic lens.

The Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) Movement has emphasized the need for divestment from collaborations with Israeli institutions that would fund and conduct activities that contribute towards the genocide of Palestine.24 A major contradiction in the marine sciences in occupied Palestine was the development of research centers in Israel, the majority of which are state-owned (one example in the marine sciences is the Israel Oceanographic and Limnological Research Institute). Even if these institutions conduct collaborative and innovative research on climate change and oceanography with other foreign institutions, such scientific lessons are obfuscated by the major contradiction of settler colonialism on occupied Indigenous land.25

Many marine conservation initiatives champion equity of marine research and conservation through an inclusive environmental justice approach.26 But without addressing settler colonialism of Palestine supported by US imperialist domination, these conservation initiatives are reformist at best, and uphold the capitalist system at worst.27 The Israeli occupation of Palestine mimics the colonization of Indigenous lands in what is currently the United States and Canada, including genocide and erasure of Indigenous peoples from those lands for European colonizers. Many of the academic and non-profit institutions in the US started moving towards making land acknowledgments, which are statements that highlight the history of those Indigenous lands and peoples these institutions are occupying. However, such gestures are empty and sometimes hypocritical given how those same institutions are also complicit or actively fund aspects of the Israeli settler-colonial project.

The scientific community at large are at a major crossroads in how they should respond to the most publicized genocide happening in Gaza, including those in the ecological, environmental, and marine sciences. Many of these institutions and organizations where these scientists are located show complicity in their erasure of pro-Palestine voices. Meanwhile there has been some attention to “decolonizing” science in academic institutions and professional organizations in recent years.28 However, much of that movement has been rhetorical and not based on organized material action.29 The scientists’ responses to the occupation of Palestine, especially in light of the genocide in Gaza, is a litmus test of the consistency (or hypocrisy rather) of scientists and their institutions’ commitment to social justice and decolonization.

Academics and scientists who are speaking out against the genocide and occupation are facing overt repression and silencing from the institutions that claim to be equitable and just. The multitude of university encampments, organized by student and community groups that demanded disclosure and divestment of universities from the Israeli occupation, was the most recent form of protest and escalation against the academic complicity of genocide and occupation. Of the many students and community members standing in solidarity with the encampments, few among them are natural scientists. However, the increased protests, encampments, statements of support, and other actions that academics and scientists partake in demonstrate the changing climate of the Palestinian solidarity movement worldwide.

In the belly of the imperialist beast that is the United States, any scientist that claims to be for “decolonization” must develop their political consciousness to foster international solidarity that is both anti-colonial and anti-imperialist. A scientist that receives research funding from the military or multinational corporations with ties to the occupation cannot be for decolonization. Those very scientists that claim to be for decolonization must also foster international solidarity for colonized and oppressed peoples of the global south that harbor local ecological knowledge. Those who claim for decolonization need to join a revolutionary organization, be it a mass organization, a vanguard party, a coalition, or some other organized group with the goal of embedding themselves in community and serving the oppressed and colonized masses. Even in Palestine, where the scientific development has been limited, the marine science conducted there has direct implications to the Palestinian coastal communities by livelihoods of fisherfolks, health of fisheries, and the conservation of ecosystems.

With increased repression, it could not be more timely to bring in scientists, including marine scientists, into the movement to call for a permanent ceasefire and an end to the settler-colonial zionist occupation of Palestine, for the people and the environment. If not before, the time to change must be now!

Meet the contributor:

Lowell Andrew Iporac, PhD: Lowell Andrew Iporac received their PhD in biology at Florida International University studying seaweed-invertebrate epifauna interactions before moving to NYC. They are the current advocacy chair of the Association of Filipino Scientists in America (AFSA) and active in the NYC chapter of SftP. They are also currently a freelance independent marine ecologist, adjunct assistant professor at Manhattan College and adjunct educator at the Bronx Zoo.

Notes

- El-Haweet, Alaa Eldin et al., “Assessment of Purse Seine Fishery and Sardine Catch of Gaza Strip.” Egyptian Journal of Aquatic Research 30, no. B (2004): 306–314.

- Dianna Allan, “At Sea: Maritime Palestine Displaced.” In Displacement, ed. Silvia Pasquetti and Romola Sanyal (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2020), 99–115,

- Abdel Fattah N. Abd Rabou, “On the Ocean Sunfishes (Mola Mola, Linnaeus 1758) By-Caught Off the Mediterranean Coast of the Gaza Strip, Palestine.” Biomedical Journal of Scientific & Technical Research 29, no. 4 (August 20, 2020): 22624-22632, https://doi.org/10.26717/BJSTR.2020.29.004831; Abdel Fattah N. Abd Rabou et al., “An Inventory of Some Relatively Large Marine Mammals, Reptiles, and Fishes Sighted, Caught, By-Caught, or Stranded in the Mediterranean Coast of the Gaza Strip-Palestine.” Open Journal of Ecology 13, no. 2 (February 3, 2023): 119–153, https://doi.org/10.4236/oje.2023.132010.

- The World Factbook Field Listing – Coastline, accessed August 21, 2024., https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/field/coastline.

- “Gaza’s Fisheries: Record Expansion of Fishing Limit and Relative Increase in Fish Catch; Shooting and Detention Incidents at Sea Continue,” United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, November 19, 2019, http://www.ochaopt.org/content/gaza-s-fisheries-record-expansion-fishing-limit-and-relative-increase-fish-catch-shooting.

- Mohammed Abudaya et al., “Correcting Mis – and under-Reported Marine Fisheries Catches for the Gaza Strip: 1950-2010.” Acta Adriatica 54, no. 2 (2013): 241–252.

- “Israel Navy Shoots Sewage Water at Gaza Fishermen,” Middle East Monitor, September 8, 2023, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20230908-israel-navy-shoots-sewage-water-at-gaza-fishermen/.

- Abdel Fattah N. Abd Rabou, “Sightings and Strandings of the Cetacean Fauna in the Mediterranean Coast of the Gaza Strip, Palestine.” Israa University Journal for Applied Science 5, no. 1 (October 1, 2021): 152–186, https://doi.org/10.52865/NUWV7692.

- Izzat Feidi, “Under Siege.” Samudra 27 (December 2000): 10–15, https://www.icsf.net/samudra/under-siege/.

- Doaa M. Hussein et al., “Status of Fisheries in Gaza Strip: Past Trends and Challenges.” International Journal of Euro-Mediterranean Studies 15, no. 2 (2022): 179–216, https://emuni.si/ISSN/2232-6022/15.179-216.pdf.

- Mohammed Abudaya and Philippa Ehrlich, “Devils’ Advocates: Conserving Mobulas in Gaza.” Save Our Seas Magazine, June 10, 2016, https://saveourseasmagazine.com/devils-advocates-conserving-mobulas-gaza/.

- Mohammed Abudaya et al., “Speak of the Devil Ray (Mobula Mobular) Fishery in Gaza.” Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries 28, no. 1 (March 1, 2018): 229–239, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11160-017-9491-0.

- Andrea Marshall et al. “Mobula mobular (amended version of 2020 assessment).” The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2022: e.T110847130A214381504, accessed https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-1.RLTS.T110847130A214381504.en.

- Abudaya and Ehrlich, “Speak of the Devil Ray,” (2018).

- Dianna Allan, “At Sea,” (2020).

- Annelien Groten, “Between Aid and Action: Aid, Empowerment and Resistance amongst Fishermen in the Gaza Strip” (PhD diss., Instituto Universitário de Lisboa, 2021).

- Abdelhakim Abu Riash. “Gaza Fisherfolk Can Only ‘Dream of Fishing Freely’ under Israel’s Blockade.” Al Jazeera, August 23, 2023, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/8/23/gaza-fisherfolk-can-only-dream-of-fishing-freely-under-israels-blockade.

- Abubaker Abed. “Palestinian Fishermen Face Death as They Try to Feed Starving Gaza.” Middle East Eye, March 5, 2024, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/war-gaza-israel-palestinian-fishermen-risking-lives-feed-starving.

- Brendan O’Malley and Wagdy Sawahel. “Israel Bombs Gaza University, Alleging Use by Military.” University World News, October 12, 2023, https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20231012162739531.

- Abdel Fattah N. Abd Rabou. “The Palestinian Marine and Terrestrial Vertebrate Fauna Preserved at the Biology Exhibition, Islamic University of Gaza, Bombarded by the Israeli Army in December, 2008.” Israa University Journal for Applied Science 4 (October 1, 2020): 9–51, https://doi.org/10.52865/HFRS6095.

- “Akhziv National Park – Main Points of Interest”, Israel Nature and Parks Authority, accessed August 22, 2024, https://en.parks.org.il/reserve-park/akhziv-national-park/.

- Peter Lagerquist, “Vacation from History: Ethnic Cleansing as the Club Med Experience.” Journal of Palestine Studies 36, no. 1 (October 1, 2006): 43–53, https://doi.org/10.1525/jps.2006.36.1.43.

- Bernauer, Warren, and Robin Roth. “Protected Areas and Extractive Hegemony: A Case Study of Marine Protected Areas in the Qikiqtani (Baffin Island) Region of Nunavut, Canada”, Geoforum, 120; (March 1, 2021): 208–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.01.011.; Bennett, Nathan James, Hugh Govan, and Terre Satterfield; “Ocean Grabbing”, Marine Policy 57 (July 2015): 61–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2015.03.026.

- BDS Movement. “Academic Boycott,” June 15, 2016. https://bdsmovement.net/academic-boycott; Bryant, Katherine L. “Palestine and Science: An Interview with Hilary Rose & Steven Rose,” Science for the People Magazine, May 9, 2020. https://magazine.scienceforthepeople.org/vol23-1/palestine-and-science-an-interview-with-hilary-rose-steven-rose/.

- Mohammed, Ryan S., Grace Turner, Kelly Fowler, Michael Pateman, Maria A. Nieves-Colón, Lanya Fanovich, Siobhan B. Cooke, et al. “Colonial Legacies Influence Biodiversity Lessons: How Past Trade Routes and Power Dynamics Shape Present-Day Scientific Research and Professional Opportunities for Caribbean Scientists.” The American Naturalist 200, no. 1 (July 2022): 140–55. https://doi.org/10.1086/720154.

- Nathan J. Bennett, “Mainstreaming Equity and Justice in the Ocean”, Frontiers in Marine Science, 9 (April 20, 2022). https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.873572.

- Mordecai Ogada, “Decolonising Conservation: It Is about the Land, Stupid”, The Elephant, 27 (2019). https://resourceafrica.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Ogada-2019-06-27_The-Elephant-Decolonising_conservation_it_is_about_the_land_stupid-1.pdf; Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. “Ten Theses on Marxism and Decolonisation,” September 20, 2022. https://thetricontinental.org/dossier-ten-theses-on-marxism-and-decolonisation/.

- Dyhia Belhabib. “Ocean Science and Advocacy Work Better When Decolonized.” Nature Ecology & Evolution 5, no. 6 (May 12, 2021): 9–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01477-1.

- Tuck, Eve, and K Wayne Yang. “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1, no. 1 (2012): 1–40.