How I Became an Occasional Cartographer

A Review of This Is Not an Atlas

By Emma Harnisch

Volume 22, number 2, Envisioning and Enacting the Science We Need

Growing up, there was a globe on my family’s living room table. My brother and I would play “vacation,” spinning the globe and dragging our fingers along the rotating lines of latitude. Wherever our fingers pointed when the globe stopped was where we were headed. More often than not we ended up in the Pacific Ocean or the vastness of Russia or the brightly colored United States. We took that globe at face-value, believed its truths, and never questioned its depiction of the world. We did exactly as the makers of this globe intended: understood it as a truth document, an authoritative depiction of the world we inhabit.

Atlases gained popularity in the late sixteenth century and boasted “true knowledge about the surface of the earth.” These atlases were being published in parallel with new scientific surveys, explorations, and theories that similarly attempted to describe the universe with detached and simple symbols aimed to divide, claim, and conquer. Fast-forward to the twenty-first century: geographic information systems (GIS) software and mapping technology have boomed, and “we live in a totally mapped era,” relying on visualizations of our world that we take to be as completely neutral, and, thus, completely truthful. Consider how you navigate to and learn about a new place—usually from an online map, created with data collected by intense monitoring of our landscapes and peoples, priming our initial interactions with both.

Now a teaching assistant in a GIS lab, I have learned to question maps like those I played with as a child: by asking who they were constructed by and for, and by listening to histories that are not my own. Many such histories can be found in This Is Not an Atlas, a collection of maps and essays compiled by a fluid network of critical geographers and activists called kollektiv orangotango+. The maps and texts come from individuals, groups, and movements around the world, bringing a vast range of contexts to bear on these questions of how maps imbue, through size and symbol, messages of power and subtle (or often not-so-subtle) domination. The atlas answers by “mapping back” and showcasing the myriad ways in which people experience place and space as an act of resistance.

Made outside the hands of power, these counter-cartographies offer new ways of visualizing our world, a reclamation and rebirth of cartography. Within each chapter we hear of new twists on counter-cartography; however, the collection of maps remains steadfast in its understanding that cartography is “complicit in the history of colonialism and nationalism and… contribute[d] to their stabilization and legitimization.” Counter-cartographies expose exploited and marginalized histories through new critical theory and political practices from artists, academics, activists, and really, anyone thinking about the space around them. In the process, they provide inspiration to envision our scientific practice and the ways we chart our explorations.

As a technical field so enmeshed in tradition, mapping often pushes critical thinking to the wayside. In contrast, but from the start, This Is Not an Atlas engages readers with a critique of the status quo and its methods. In the Amazon, the Projeto Nova Cartografia Social de Amazônia (PNCSA) presents “A New Social Cartography” that exposes the appropriation of participatory and community-based methods of mapping by major corporations, especially in indigenous Brazilian territory. This resource-rich region is under particular attack by loggers, miners, ranchers, and state-backed land developers who seek to take power from the land and people.1

Participatory mapping invites the input of the entire community, centering marginalized experiences to influence planning and land protection. Erupting out of attempts to address classist and racist scientific research methods beginning in the late 1930s, participatory mapping quickly became a tool used by working class and indigenous people to expose social inequalities and protect their lands around the world.2However, as the PNCSA notes, these tools have since been appropriated by major corporations to turn “‘participation’ into mere ‘ratification’ of decisions taken by someone else.” So how can communities map back against corporations that will readily appropriate these tools to further their own goals toward control?

One possible answer can be found nearby in Argentina, where the mapping duo the Iconoclasistas facilitates counter-mapping workshops in communities fighting back against massive monoculture agribusiness and open pit mega-mining that leave both the people and the land sick for generations. It is striking to see a workshop map of the Andes smattered with symbols of skulls and crossbones, bulldozers, clenched fists representing sites of toxicity, extraction, and resistance. By widening even just the set of symbols used, these maps paint a clearer picture of what is going on, who is involved, and the geographic relationships between the state, transnational corporations, and the exploited communities rising up and demanding justice.

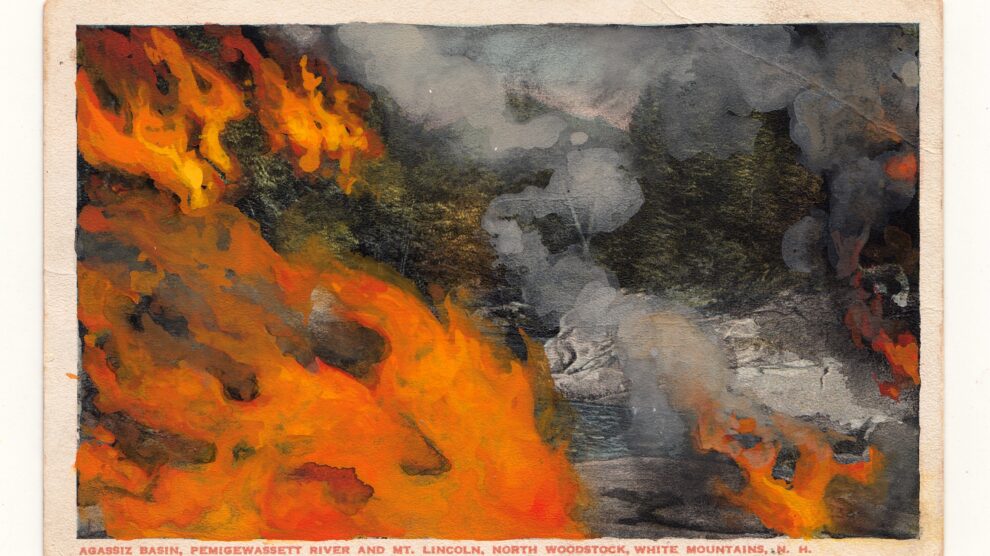

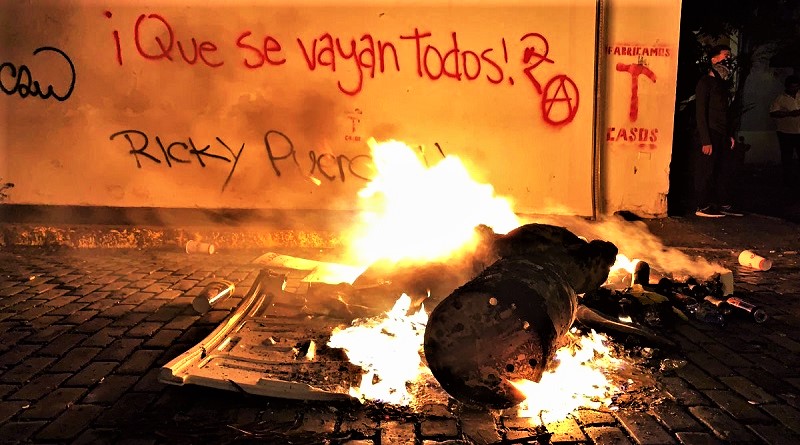

The Iconoclasistas also helped facilitate a workshop in Valparaiso, Chile after a major urban-rural fire swept through major neighborhoods of the city. The collective map they made is called “Did I invite you to live here?”—a reference to a cruel remark from Valparaiso’s former mayor to neighborhood activists following the fire, but also a succinct and frank description of the issues facing the city’s people. Participants discussed how, through counter-mapping, “the main problems of the area slowly became visible; they were associated with the processes of gentrification and privatization of the city.” Projects like this take the tools used to justify neocolonial and neoliberal agendas and flip them upside-down, enabling us to see the true connections between geography and power.

This Is Not an Atlas takes the reader around the world: to the Philippines, where Cian Dayrit uses art to tackle the inaccessibility of traditional mapping, to the US, where the Counter-Cartographies Collective highlights the ways educational spaces are complicit in exploitation, to the Amazon, and elsewhere. In the process, it features dozens of interventions into the ways mapping is both used and taught and provides lessons not only to cartographers but also to the larger scientific and educational communities. The atlas’s vastness in approach, medium, and context shows how we can resist a worldview embedded with oppressive power, and science workers across all disciplines should take note.

What I love most about This Is Not an Atlas is its guide on How to Become an Occasional Cartographer. This chapter includes three separate how-to guides on creating your own counter-maps, inviting readers to map their own communities, movements, and stories and add to the incredibly diverse array of geographies they represent. The guides highlight how to incorporate GPS (global positioning systems), facilitate workshops, and reflect on lessons learned. We learn how to make counter-maps not to just make more maps, but to visualize power and to act. This process puts the power into the hands of those who have been mapped without consent and those who will never appear on the map, those who are fighting against the ways land and people have been navigated, explored, and claimed. This is the epitome of an anti-atlas: new truths created and legitimized outside of ivory towers, classified documents, and social hierarchies. There is no gatekeeping that locks this information away, but rather an invitation to those who were never supposed to possess the power to make documents of truth. This is solidarity science in action.

This Is Not an Atlas

Edited by kollektiv orangotango+

Transcript-Verlag

2019

352 pages

About the Author

Emma Harnisch is a geologist-turned-geographer, writer, teacher, and map-enthusiast in Western Massachusetts. Emma is currently the Spatial Analysis Fellow for Smith College where she earned a degree in Geosciences. While not thinking about maps, Emma is writing alternative curricula for geology and environmental science classes that intersect concepts of social, political, and economic power. She is a dedicated member of Science for the People where she organizes locally and serves in Science for the People magazine editorial collectives.