October 16, 2024

The Struggle for University Divestment in the Age of Finance Capital

G. W. Castro

Over 365 days have passed since the Zionist entity and its sponsors in Washington, D.C. launched their genocide in Gaza. Hospitals, schools, mosques, homes, refugee camps, bombed to rubble. A chokehold on Gaza’s access to basic supplies—tightening the already barbaric siege imposed on the Strip since 2007—so complete that an outbreak of polio looms. Tents fire-bombed; children torn to shreds with bunker-busters or murdered by snipers; captives tortured and gang-raped; war crimes routinely committed against civilian “targets” in Gaza, the West Bank, and now Lebanon and Syria, without tactical purpose—just wanton savagery and destruction.

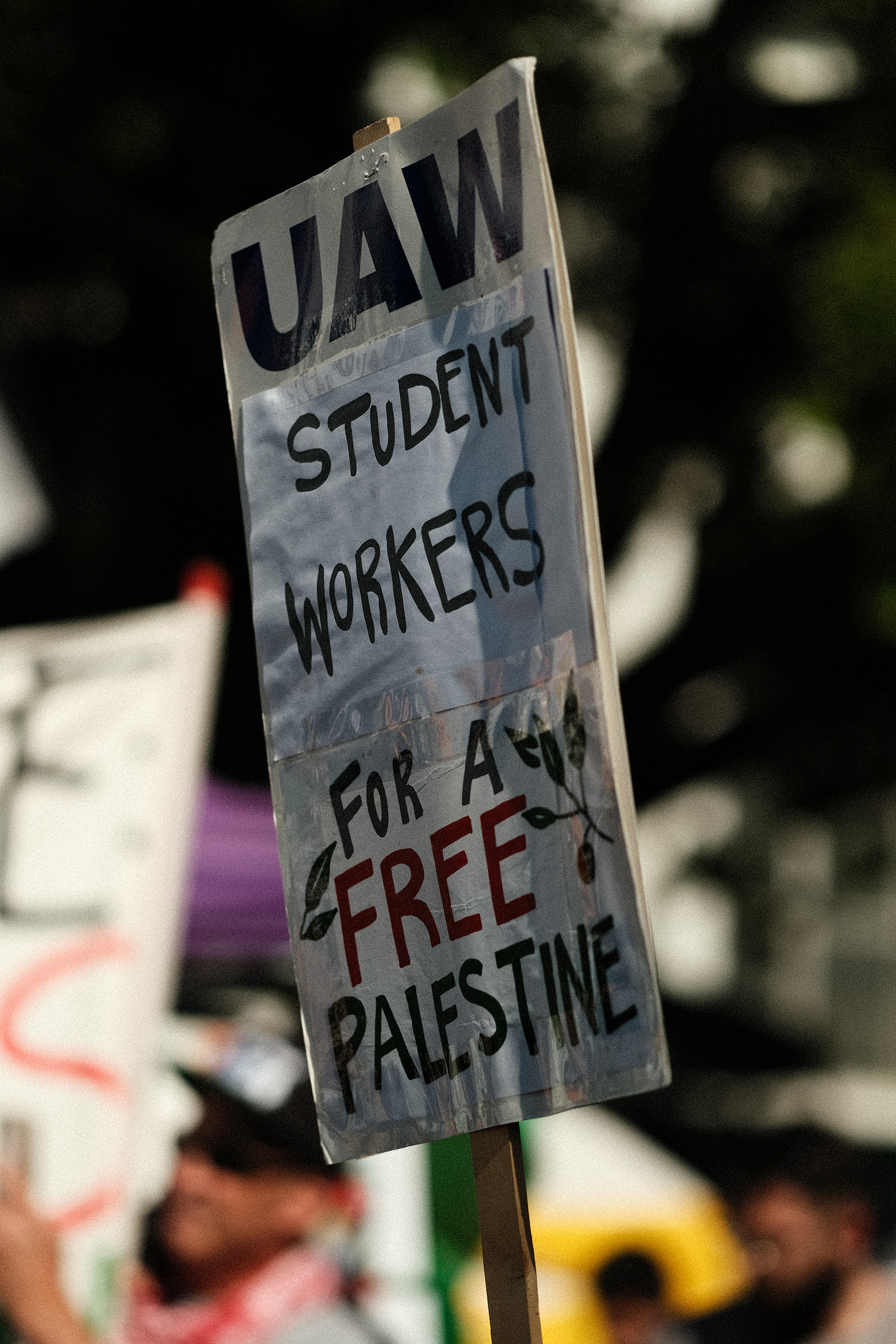

Despite the impressive efforts of the imperialist media at whitewashing these atrocities, the Palestinian solidarity movement in the Global North grows by the day, and students are among the most active elements within it. At the University of California, undergraduate and graduate students were part of the nationwide wave of encampments this past spring demanding divestment from Israel. UCLA, Santa Barbara, Santa Cruz, San Diego and Irvine were attacked by riot police on orders of UC administration. UAW 4811, the local representing teaching assistants, researchers, postdoctoral and staff academic workers across the UC system, responded by calling a strike, which lasted three weeks until the UC acquired a restraining order to forcefully bring it to an end.

In the aftermath of these actions, it is important to survey the strategic landscape for the next phase of divestment organizing. Writing from the perspective of an organizer in the UC Berkeley BDS Exploratory Committee,1 I argue here that our movement must reckon with the financialization of U.S. universities—their subjection to the imperative of growth and reliance on interest-accruing wealth to reproduce themselves—and that the latter partly explains why the BDS movement faces such intense repression. I further argue that academic student-workers, who are well-positioned at the intersection of the student revolts and the labor movement in higher education, have a unique opportunity and obligation to participate in this struggle.

What forbids university administrators from giving in to our movement’s demands is not the influence of any special interests. Rather, the boundaries that separate higher education from “the rest” of the capitalist economy have eroded, imperfectly and unevenly but to a sufficient extent that the systemic force of financial markets dictates investment decisions and makes universities hard to distinguish from banks. What’s more, it is the maintenance of the imperialist world system altogether—the conditions required to maintain the current regime of accumulation—that forbids them from breaking with Israel. The rulers of the university look after their own interests, as they always have, but not strictly under conditions of their choosing; they do so on pain of committing “class treason” should they act against the stability of accumulation in the imperial core. Accordingly, the university administrators to whom we address our demands cannot be engaged merely as individuals, but as members of a class who share common interests in preserving the status quo.

The university as the site of struggle

In 1968, amid world-wide protests against the Vietnam War, hundreds of students at Columbia University occupied buildings as they demanded that the university end a racist expansion project into a nearby public park and sever ties with the U.S. war and intelligence machine. Organizers at that time produced the Who Rules Columbia? pamphlet, in which they described “the control of the university by outside corporate forces … especially real estate, militarism, and finance.”

In the 1980s, students led an unprecedented wave of divestment campaigns across the U.S., demanding that their schools divest from the apartheid state of South Africa and companies that profited from it. At the UC in 1985 students led a series of civil disobedience actions, including a “shanty town” occupation of Sproul Plaza at UC Berkeley, and ultimately pressured the UC to divest $3 billion a year later.

We can trace an interesting difference between the ‘68 and ‘85 student movements. Besides their university’s research and academic ties to the Pentagon and the U.S. war machine—to which we’ll return later—the Columbia students’ struggle in 1968 pitted them against university trustees using their position to enrich themselves and their business partners. In contrast, the movements around ‘85 were attempting to hack away at universities’ financial ties, through their investment portfolios, to the state of South Africa—financial ties which existed not because of individual administrators’ greed, but because the entire business model of higher education was being financialized and thereby subsumed into the worldwide process of accumulation. The latter—which, especially after the 1970s, was increasingly dominated by finance capital—depends for its development on the transfer of value from the periphery nations of the Global South to the imperial core through super-exploitation, unequal exchange, forced underdevelopment and wars of counterinsurgency.

It should come as little surprise that the strategic landscape BDS student organizers face today is largely shaped by the advancement of university financialization

One should not take this temporal dichotomy too seriously. Though perhaps different in form, Columbia’s “rule” by self-dealing defense executives and real estate moguls conformed with the functioning of U.S. imperialism no less than modern university investment practices do. And indeed, the ‘68 uprisings existed at the nexus of the anti-war, black power and civil rights movements, and worldwide struggles for decolonization. To say that the students’ immediate antagonist was the control of their university by corrupt oligarchs—and not the interests of Wall St. or the U.S. State Department, or the comprehensive regime of counterinsurgency deployed against progressive movements everywhere as the U.S. and its allies attempted to eradicate anti-colonial, communist and national liberation movements across the Global South—is only possible if we’re narrowly focused on how these dynamics manifested within the North American university at the time.

Nevertheless, with the benefit of hindsight we can see that this shift in appearance, at least, of the primary antagonist—from a kind of special-interest cronyism to the rule of Wall St. itself—exactly coincides with the trend of neoliberalization and financialization in U.S. higher education. It should come as little surprise, then, that the strategic landscape BDS student organizers face today is largely shaped by the advancement of university financialization. Now more than ever, to analyze the tactic of divestment we must understand the university’s role as an investor, i.e. as a capital-accumulating institution.

Hedge funds that conduct classes

Here, “capital” doesn’t mean money; it means money and assets whose purpose it is to grow and yield returns (profit, interest, or rent) to whoever owns it. University endowments weren’t always “invested” with an eye towards growth—they were spent on university operations and replenished, through gifts and philanthropy, so as to keep the endowments’ value roughly constant. Around the 1970s that began to change, and U.S. universities became increasingly concerned with using their endowments as capital—as value that would accumulate over time, primarily as interest—through finance. This was the period of “stag-flation,” or the crisis of overaccumulation after thirty years of post-war growth. As profitable investment opportunities in commodity production became increasingly scarce, capital found an outlet in the financial system, and new types of financial instruments mushroomed into existence as corporations funneled their surplus into speculative assets and investments in the FIRE (finance, insurance, real estate) sector.

So, unlike in the 1960s, by the 80s university endowments were sufficiently financialized that the tactic of divestment could be taken up en masse by student activists against their universities, some twenty years after South Africans had begun to call for the economic isolation of South Africa—largely through sanctions and embargoes—as one prong in their struggle. For students in the United States, then, what mattered was less the greed of their university administrators and more the intransigence of the U.S. ruling class as a whole—which had no interest in economically isolating South Africa so long as it was profitable and served U.S. interests in the region—and the financial “business model” that administrators were pursuing. With universities’ core function and ability to reproduce themselves tethered to the movement of finance capital, they became essentially “hedge funds that conduct classes.”

The nature of the capitalist university necessarily puts its administrators into a position of antagonism with both its students and workers.

While plenty of university administrations have continued to indulge in the sort of shameless racketeering2 that the Columbia ‘68 students chronicled in their pamphlet—and the University of California is no exception—the important point is that even when they do not try to embezzle for their own private gain, the nature of the capitalist university necessarily puts its administrators (regents, trustees, chancellors, etc.) into a position of antagonism with both its students and workers. This structural antagonism goes some way towards explaining the ferocity with which universities attempt to suppress the BDS movement. To complete the picture we must look to the underlying process of capitalist development in which the university’s “bottom line” is embedded—a worldwide process of accumulation where the U.S.-Israel “special relationship” plays a crucial role.

For the United States it is unthinkable to accept Palestinian sovereignty and thus lose its proxy state in the Levant. This would mean the vaporization of actual and potential value chains—in the form of high-tech development and exchange, real estate, and access to strategic resources—that have been carefully cultivated by Western imperialists since 1948. The decision to aid and abet the holocaust in Gaza, despite the risk of Israel triggering a regional war, is rational from the perspective of capital. Were an independent Palestinian state allowed to exist, it could lead to a regional pole of economic sovereignty, which must be avoided at all costs—the entire pattern of accumulation in the imperial core depends on forced underdevelopment and depressed wages in the periphery, unrestricted mobility of capital, and the neutralization of peripheral or semi-peripheral powers that could challenge Western domination.

For university administrators, it is likewise unthinkable to step even one toe out of line with this ruling-class consensus, enforced for the past half-century by the vicious disciplining of dissent at any level of American media, academia and politics. What other political issue would have led UC President Michael Drake—just weeks after the Bay Area recorded another surge in COVID cases—to effectively ban masking in public spaces on campus, in a hysterical effort to contain pro-Palestine protests at his university? Even if Board of Regents Chair Richard Leib did not parrot despicable, racist anti-Palestinian propaganda, is it conceivable that the Regents would ever meet calls for divestment with anything but repression? The individual beliefs of this or that spineless university official hardly change the fact that, unless the decision is all but taken out of their hands, their ceding a single inch to the pro-Palestine movement would constitute political, career, and business suicide. To bring this much force to bear—to force their hand—is precisely the task of our movement.

Organizing for divestment in the belly of the beast

Forty years after the South African anti-apartheid struggle and wave of related divestment campaigns, the financialization of American universities is in its advanced stage. One simple illustration of this is the fact that university investments are now overwhelmingly held through financial instruments like index funds, mutual funds, commingled funds, etc.—that is, highly mediated forms of investment. Today the University of California would (mostly) not directly hold shares of companies doing business in South Africa; it does not directly own shares of almost anything. When it comes to Israel, with a few exceptions the UC does not invest in the bomb-makers and apartheid-profiteers directly; it lets professionals like BlackRock do it on its behalf.

Of course, this does not mean that the university is unconcerned with or uninvolved in the investment process. For example, indirectly holding equity in a company entitles an investor to proxy votes in the company’s governance, which the UC Investments Office is more than happy to use. The UC used its proxy voting power in Elbit Systems Ltd. in April, 2024—with the noble goal, one assumes, of instituting “responsible” management practices as it rakes in its proceeds from the slaughter of Palestinian civilians.

So, what practical lessons must we draw from this in our organizing? First, universities’ financial ties to the Israeli occupation (and to weapons manufacturers, and to anything else, for that matter) are both more opaque and more pervasive than ever before.

Second, university administrators can and will attempt to absolve themselves of any responsibility for their investments. They didn’t decide that the ethnic cleansing of Palestine is good for business, the market did! They will claim they cannot force index funds and asset managers to divest from genocide, which is partly true and partly false: it’s true that, though there do exist specialized funds which exclude weapons manufacturers,3 no public index fund currently exists that screens out companies, say, with operations in Israel. However, universities can do “direct” indexing (i.e. directly buying stocks in proportions corresponding to an index) or request “customized” index funds, which allow the investor to adjust and exclude companies essentially by hand. In fact, the UC worked with MSCI to create a fossil fuel-excluding index fund, which is now available not just to the UC but as a public, off-the-shelf index fund. Mutual and commingled funds, in which the university is just one of several client-investors and cannot unilaterally compel a change in policy, are indeed trickier. In this case universities could adopt a kind of “short-selling” policy towards divestment, wherein they would offset any indirect exposure they have in an offending company by shorting an equivalent amount of that company’s stock.4 As for separately managed accounts or SMAs, in which an external firm acts as manager but the investor retains direct ownership of assets, universities have full discretion over which securities to purchase or screen out. This is precisely the UC’s current divestment policy with respect to companies that operate in Sudan.

Third, university investment committees have had time to put up defenses with which to insulate themselves from student interference. Here’s a simple example: the UC Berkeley Foundation, the entity that manages Berkeley’s endowment, has official divestment guidelines in place. These state (emphasis added) that “divestment-related actions may include … divestment of direct investment in the equity and debt securities of a company, [and] in the case of commingled funds, discussions with the fund managers.” Here divesting commingled funds entails nothing more than a “discussion,” and non-commingled indirect holdings, such as index and mutual funds, are not even mentioned. Only for direct investments does “divestment” imply anything of substance. So, as indirect investments make up most of the portfolio, the official divestment process is thereby neutralized: even if all the layers of committees, advisors and trustees voted to “divest,” the amount of money actually changing course could be very meager.

Fourth, appeals to morality fall on deaf ears. The carnage in Gaza is what our ruling class has decided will be normal. Taking a single step towards divestment is simply not conceivable to our university administrators; they will ignore, stall, or retaliate at every opportunity. The only way divestment will happen is if they have no other plausible choice; if they feel the university will cease functioning unless they give in.

Not just banks

While maintaining a kind of side hustle in education, as a functional bank the university’s primary duty is to ensure growth: a portfolio with good year-over-year returns, expanding campuses and buildings, healthy income from real estate, and so on. Demonstrating that the university has good growth prospects independent of public funding is vital to secure further investments from financiers and industry partners, and to therefore ensure the university can survive future cuts to public support for higher education.

Of course, research and education are embedded in this self-reinforcing cycle. Prestige, growing student enrollment, high research output and incoming research grants, prestigious faculty recruitment, and partnerships with industry and national research labs are all excellent ways for universities to make themselves appealing to investors. For these and other reasons, administrators are certainly not indifferent to the teaching and research that take place in their university; they just care about them for reasons that are, typically, antagonistic to the interests of students, workers, and the community.

If “decolonizing the university” is to be anything more than a metaphor, this is what is demanded of us: an understanding that goes beyond trite condemnations of “militarism” or greed, and analyzes universities’ joint role as both investors and engines of accumulation.

In fact, insofar as universities produce teaching and research, they are qualitatively different from Goldman Sachs and BlackRock. Research and education are simultaneously those parts of the university which cannot be completely absorbed by finance and which contribute uniquely (non-financially) to the maintenance of U.S. hegemony. The products of academic labor fulfill a particular kind of ideological and technological function5 for U.S. imperialism and, concretely, for the Israeli occupation. This state of affairs is little-changed from what the anti-war movements of the 1960s and ‘70s charged American universities with: collaboration—by providing scientific research to the Pentagon and selling libelous, revisionist propaganda to the American public—with U.S. atrocities in Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, and Indonesia, to name a few.

Therefore, along with viewing universities as financial actors, we must understand (i) how their research output fits into the American imperial project and (ii) how as academic institutions they legitimate and provide cover for the Israeli occupation. A more detailed study of the function of research and knowledge production in the economy of the imperial core must be undertaken. If “decolonizing the university” is to be anything more than a metaphor, this is what is demanded of us: an understanding that goes beyond trite condemnations of “militarism” or greed, and analyzes universities’ joint role as both investors and engines of accumulation.

Upending the status quo

Despite the process of integration we have described above, the university remains imperfectly subsumed into capitalist production—viz. the fact that academic workers’ “boss” is also usually their mentor and that the former are expected to (and usually do!) work beyond what their contracts demand, out of passion for their discipline. This is a vestige of the more traditional master-apprentice academic relation, coexisting uneasily with the increasing precarity and downward mobility of academic labor (which therefore increasingly sees itself as “academic labor”). Likewise with the fight for divestment, universities are not to be viewed as businesses, pure and simple. Schools cannot control how their students spend their time as finely as employers can with their employees; indeed this is one reason why “student” movements have been historically common enough to warrant their own category. Moreover, universities are meant to provide a public good. Their subjection to the whims of finance capital notwithstanding, the mandate to “do right” by their community carries at least some weight, which cannot be said of asset management firms or tech giants. These contradictory qualities must be grasped both as brewing crises and, potentially, opportunities for our movement.

The Zionist entity has begun its collapse. Its economy is imploding, with investments in the Israeli tech sector drying up and a housing crisis (and shortage of super-exploited Palestinian labor to mend it) looming. Even on the ideological front, the Western propaganda machine is faltering, Israel’s barbarities and the imperialist media’s lies finally becoming too much to swallow. The cracks are indeed forming, but they do so only through struggle. For the organized solidarity movement in the Global North, the task is clear: support the Palestinian resistance, whatever form that takes—the strike, the streets, the disruption of Israeli weapons supplies. As I’ve attempted to argue here, the contest of power within the university offers one such pressure point. The internal contradictions of the university, where more than forty years of austerity and financialization have nearly gutted and co-opted its social function and replaced it with the hollow growth imperative of capital, simultaneously create its own opposition: mass uprisings of students watching their schools funnel their tuition toward genocide and a growing academic labor movement with the potential for radicalization. More concretely, organized academic workers will be relevant if we are willing to use the weapon that student movements in the past could not: the protected right to withhold labor. Narrow trade union consciousness won’t do here; if we are to play any sort of progressive, anti-systemic role in this struggle we must break with the worst traditions of Global North unionism (imperial collaboration and apologetics, national chauvinism, don’t-rock-the-boat business unionism). Anything less is tacit or explicit support for the status quo.

This is not to overstate the importance of the university in the broad movement for Palestinian emancipation—which is waged first and foremost, as in any anti-colonial struggle, by the armed Palestinian people and resistance forces allied against their oppressors—but it is to acknowledge the real conditions of turmoil latent in it. Here, to fight to divest and weaken the stranglehold of finance capital on our supposedly social institutions is to create (or intensify) a crisis for the ruling class, and to support the Palestinian national liberation struggle from within the imperial core. This article was only an attempt to sketch out the terrain in which our fight must continue. The current genocide will end, but the Palestinian resistance will not, and our movement’s task will remain unchanged until the occupation falls.

—

G. W. C. is a Physics student and organizer in Berkeley, California. He is a member of UAW 4811 and Science for the People. Thank you to C. W. for editing this article and for the helpful discussions throughout.

Notes

- The BDS Exploratory Committee was formed by academic workers in the winter of 2023–2024 to investigate the UC’s investments and devise a labor strategy to force its divestment from Israel. The committee’s report, “Who Rules the University of California?,” is due to be published soon. Its title takes inspiration from the Columbia ‘68 students’ pamphlet.

- Nor have the bankers and war profiteers left university management—far from it. Most high-level university administrators come from finance, politics and business, including the defense industry.

- In fact, divestment from the defense sector could in some sense be a “milder” ask than divestment from Israel. Anti-war sentiment has bubbled up with varying degrees of intensity in the past; universities divesting from weapons manufacturers might therefore be more easily taken by investors as indulgent administrations caving to their students’ hippie sensibilities, rather than a fundamental threat to the status quo. Divestment from Israel would signal a more profound shift in popular consciousness (and crisis for the current mode of accumulation). This in no way implies, of course, that divestment from the defense industry ought not to be part of our struggle, or that universities won’t fight tooth and nail against it.

- For example, if it has $X indirect exposure (through a mutual fund, say) in company Y, the university borrows $X worth of stock in Y from a third-party broker and then immediately sells it at market price. The university promises to rebuy this stock and return it to the broker at a later date, but by immediately shorting this stock the university has in effect “divested” by taking out $X from company Y’s stock (and thus lowering its price). Meanwhile, whenever the university’s indirect holdings in Y gain value the short loses the same amount of value, and vice versa. It’s not a particularly elegant approach, but it’s also not the inelegance that universities will object to, anyways.

- Including, but not limited to, the production of weaponizable research.