December 6, 2025

The Paradox of Hope: When Science Forgets the Body

A Personal Essay on Medicine, Vulnerability, and the Limits of Progress

By Mihaela Răileanu

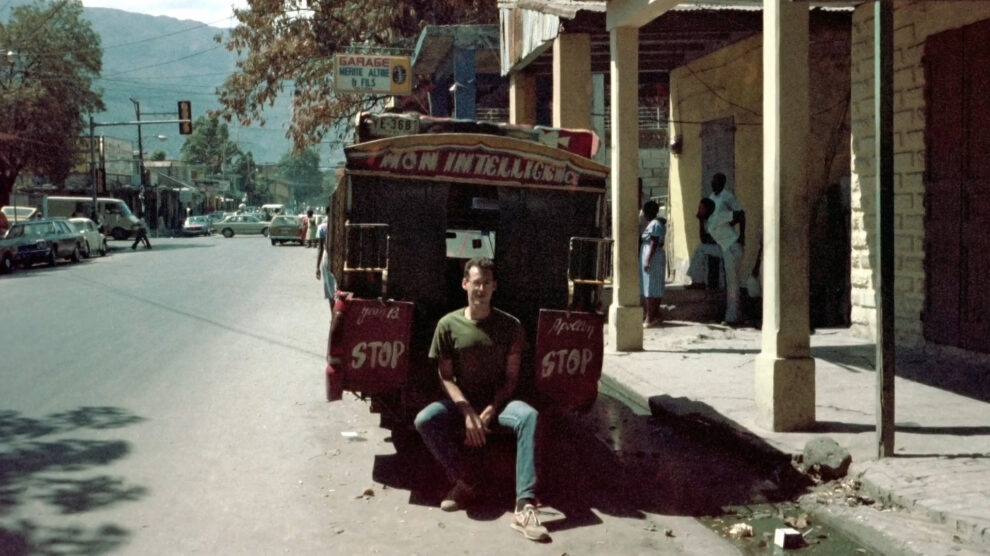

In Romania, where healthcare oscillates between underfunded public hospitals and costly private clinics, illness quickly becomes a social diagnosis. This is a story about what happens when medicine meets the limits of care—set in contemporary Romania, yet recognizable far beyond its borders.

May 5, 2024. Easter morning.

I woke up and realized I could barely see with my left eye. The world looked blurred, as if behind a thick fog. At first, I thought it was something temporary. That day was bright and full of guests, the air smelled of spring and new beginnings. Ironically, I felt wonderful. I laughed, I told stories, I made plans.

A few weeks earlier, I had quit a stressful job and finally felt I could breathe again. I wanted to write, to draw, to read the stack of books I had postponed for months. But my plans were about to be put on hold.

By Wednesday, I had learned how fragile the word ”temporary” could be. My left eye didn’t recover, not with more sleep, not with rest, not with giving up screens.

Still, in those first few days, I wasn’t afraid. I truly believed everything could be healed. And that no illness could ever silence my creative energy.

The Maze of Medicine

After the Easter break, the nightmare began. It’s hard to say what was worse: the neurological diagnosis or the endless pilgrimage between private clinics, medical offices, nurses, receptions, and long white corridors. The overwhelming feeling was that I had entered a maze with no exit.

That first Wednesday, I still hoped that after a short consultation I would return home relieved, maybe with a prescription. I did return home—poorer, but with no answers. The private clinic I went to didn’t even have the equipment for a simple eye ultrasound. They politely sent me to a public hospital—“the doctor is going on vacation, just send the results on WhatsApp”—and advised me to bring a bottle of water, “because you might be waiting all day.”

In Romania, the distinction between private clinics and public hospitals is often blurred, even for the patients. The system is a mix of public institutions, private providers, individual practices, and ambiguous “workarounds” that force people to pay for services that, on paper, should be free.

Public hospitals are funded by the state and covered by the National Health Insurance House (CNAS). In theory, they offer free care to insured citizens. In practice, however, they are often underfunded, crowded, poorly equipped, and plagued by delays, understaffing, and sometimes even informal payments. By ‘informal payments’ I mean under-the-table cash expected by some doctors or nurses—a remnant of the post-communist healthcare culture. It is worth saying that in Romania, health insurance is universal and state-funded; private care is paid separately and accessed mostly by those who can afford out-of-pocket costs.

Private clinics look modern and offer quick, clean, polite service, but they’re not equipped for emergencies or complex interventions. Patients routinely pay out-of-pocket for consultations and tests, even when insured.

The confusion comes when these two systems intersect. Many people go to private clinics for faster diagnostics, only to be referred back to the state system for actual treatment. That means paying twice: once with money, once with time and stress.

For some, “better” means you don’t have to wait. For others, it means being treated with basic dignity. In the private sector, you get efficiency, hygiene, and a smile. In the public sector, you might find skilled doctors, ICU units, and critical care infrastructure, but also chaos, overcrowding, and missing supplies.

Doctors often work in both systems. Some examine you privately and then help you “get in” to a state hospital. Some private clinics even have contracts with the public insurance system—but it is rarely clear what’s covered and what isn’t.

Imagine going to a sleek private clinic where you are treated kindly and told what you need, but then you’re sent to an overstretched public hospital for treatment. You can’t choose your doctor. You may not find a bed. You might have to bring your own medicine. That’s how the Romanian system often works—in fragments, with gaps filled by guesswork, goodwill, or grief.

Scared to death, I chose another private clinic, a better one. The next morning, at the first hour, I was there. They did the ultrasound flawlessly. But the problem wasn’t in my eye. It was in my brain.

When a doctor tells you something you don’t want to hear, words lose their meaning. I looked at him, but couldn’t really hear. “There are treatments,” he said softly. I didn’t know if it was a promise or a statement. He sent me to the public hospital: “You need an MRI as soon as possible.”

I began to realize that what I was facing wasn’t just personal misfortune. It was the ordinary experience of being sick in Romania. Behind every delayed test or confusing referral stood larger problems that no single doctor could fix.

Romania’s public healthcare system suffers from chronic underfunding. For years, the country has allocated one of the smallest health budgets in the EU (as a share of GDP). Many hospitals are over fifty years old, operating with outdated infrastructure and unsafe electrical systems, sometimes leading to fatal fires. As widely reported by BBC, Reuters, and other international outlets at the time, fatal fires at hospitals such as Piatra Neamț and Matei Balș exposed severe infrastructure failures in Romania’s public healthcare system.[1] Salaries for doctors have increased recently, but many support roles (nurses, aides, orderlies) remain understaffed and underpaid. Preventive care and family medicine are severely underfinanced, which means most patients arrive at the hospital only when their illness has become serious or irreversible.

Beyond underfunding, the system is entangled in bureaucracy and opaque decision-making. Family doctors often spend hours filling out repetitive forms rather than seeing patients. For example, family doctors must fill out several overlapping electronic reports for the same patient visit—one for CNAS reimbursement, one for the national registry, one for internal clinic administration. Funding programs is slow, inconsistent, or blocked in committees. Hospital managers are frequently appointed through political connections, with little or no training in health administration.

At the same time, many hospitals lack essential equipment—no MRI machines, no ventilators, no protective gear— and patients are often sent across counties for basic investigations. (Romania had only 0.4 MRI units per 100 000 inhabitants in 2019, the lowest in the EU.)[2] The lack of proper infection control protocols has made hospital-acquired infections a dangerous and ignored reality.

Finally, the divide between public and private healthcare has grown into a structural split. Many doctors work in both sectors and informally redirect patients from public hospitals to private clinics for faster care. Public insurance funds are sometimes used to subsidize private institutions, creating tension and perceptions of favoritism. Access to treatment, then, is often dictated by wealth: those who can pay go straight to care, while others are lost in queues and administrative limbo.

If this is what it took to reach a diagnosis in the capital city, with access to private clinics, research skills, and institutional literacy, I can only imagine what happens to someone with the same symptoms in a remote rural village where there is no MRI machine, no specialist, and often, no one to even notice the patient’s decline.

More than that, in post-communist Romania, illness is rarely just a medical issue. For many elderly or vulnerable people, the hospital becomes the last place where they are still “seen” by someone. Once, families were central to caregiving in Romanian culture. Caring for parents, grandparents, and the ill was part of a larger, intergenerational structure of support. But post-communist transition, massive migration, and the erosion of local solidarity have created a harsh new reality: many sick or aging people are now left completely alone.

Some patients remain in hospital beds for months, not because they need intensive care, but because no one comes to take them home. Others die with no one by their side, and it’s often the nurses or doctors who make arrangements for burial. Bureaucracy compounds this abandonment: people lose access to care because of missing paperwork, expired IDs, unclear insurance status, or simply because there’s no coherent system for long-term or palliative care.

For an American reader, the healthcare system may be familiar as a space of inequality or economic exclusion. But in Romania, illness is also the collapse of the social net itself. Being sick doesn’t just cost money. It can isolate you entirely. Without family, without institutional support, people become invisible. They are passed between clinics and wards, carried by ambulances from one place to another, with no continuity or real care—just a system trying to manage “cases,” not lives.

It’s also a struggle with the system: with waiting, with bureaucracy, with the feeling that your life depends on a form or a signature. Here, even after decades of reform, an MRI remains a luxury, costing nearly half the minimum monthly wage, in a country where that wage is barely seven hundred dollars. If you want it done for free, you face endless paperwork and absurd appointments: tests at two in the morning and endless lines.

At the Emergency Hospital

The emergency hospital I arrived at felt like a movie with the sound turned up too loud: stretchers, ambulances, people crying, hurried staff everywhere.

On one stretcher, an old woman had been brought in again by ambulance. I overheard a nurse saying the woman’s son didn’t want to keep her at home. In Romania, illness isn’t just a medical condition. It’s also a form of social abandonment.

I waited for hours. A young doctor expressed surprise that I had no children. I didn’t have the energy to explain that it wasn’t mandatory—or relevant. I felt sick.

They did a CT scan, not an MRI. There wasn’t a working machine. They wanted to admit me for a lumbar puncture. I was terrified and refused. I only wanted treatment. “It’s calculated by body weight,” they said, bored. After nine hours without food or water, I went home. Exhausted, and mostly emptied of any trust.

The next morning, I paid for the MRI—of course—and a few days later, finally, I saw a neurologist. He ran test after test, more than fifty in total. The verdict came by WhatsApp: “Take folic acid for three months and we’ll see.” Folic acid? What about my eye? What about my brain?

That’s when I broke. I had lost vision in one eye, my savings, my patience, and my sleep. But I kept searching for a doctor. A better one, for my life. And one day I found a doctor who actually listened, examined me carefully, and gave me the right diagnosis. It was already too late for my eye, but not for the rest of me.

Medicine didn’t heal me. It only stopped me from falling further. It took months to enter a treatment program— months in which I felt like an object dropped between worlds: too sick to live normally, too alive to be saved. Because sometimes, in Romania, it’s not the illness that kills you. It’s the system. And the system is made of the very people who are supposed to treat you.

We are taught to trust systems—medical, digital, bureaucratic—until the moment they fail us. Illness exposes how fragile that trust is, how quickly it turns into dependence, and how dependence erodes dignity. Medicine is not only about bodies, but also about the silent politics of trust.

The Illusion of Progress

We live in a world that never stops talking about medical miracles: gene therapies, surgical robots, artificial intelligence that diagnoses faster and better than doctors. Press releases are written, conferences are held, documentaries are filmed about the future of medicine.

And yet, in Romania, a simple MRI is a luxury. For most people, progress isn’t a fact; it’s a story told to someone else—a technological fiction they will never touch.

I don’t know if it’s the fault of the system, the government, or a world that has learned to mistake technology for ethics. But what’s clear is the rupture. Science promises salvation, but forgets the living body of the patient.

In real hospitals, no one talks about innovation. They talk about waiting lists. Not about medical algorithms, but about prescriptions paid out of pocket. Not about hope, but about the exhaustion of people waiting hours for a consultation.

The harsh truth is that cutting-edge medicine coexists with anonymous suffering, sometimes just a few miles apart. Progress exists, yes, but it’s an island fenced off by money and bureaucracy. Most patients don’t live in the age of innovation. They live in the age of waiting.

We no longer speak of medical progress. We speak of the illusion of progress, a story told by those who can afford it, while the rest of the world still hopes for an MRI.

The gap between innovation and care is not unique to Romania. Even in wealthy countries, patients face different kinds of inequality—in insurance, in access, in the price of survival. We live in a world where a robot can perform heart surgery, yet millions cannot afford a basic blood test.

The Paradox of Hope

Hope is sometimes like a muscle. You train it without realizing, against exhaustion, against despair. You hope not because it’s logical, but because your body needs continuity. Hope becomes a biological reflex of resistance when science can no longer help.

A sick body isn’t just vulnerable, it’s divided between fear and trust, between what it knows and what it refuses to believe. You learn to live with your own fragility, to negotiate its limits. You learn that illness isn’t simply the absence of health. It’s a reconfiguration of meaning. That you are no longer who you were, but you still exist.

Hope is not optimism. It’s not faith. It’s a form of extreme lucidity, a discipline of breathing, a silent pact with time. It’s what keeps you whole when everything else falls apart: the body, the routine, the trust in people, in the system, in progress. There are moments when science forgets that it treats living beings, not mechanisms. In those moments, hope becomes the last remaining human space—a quiet resistance to the inhuman.

And maybe that’s why, despite every statistic, despite every failure, we keep hoping. Not because we know it will get better. But because, against all evidence, we still choose to live. When you write while ill, language itself becomes physical, a way to measure pain, to keep order when the body fails.

Toward a Human Science

I am a political scientist, a climate security researcher, and a writer. I don’t reject science; on the contrary, I hold it in deep gratitude. It is proof of human progress, of our capacity to overcome limits and to save lives. Every step forward in science has been made through effort, courage, and hope. Many of us—myself included—are alive because of that collective achievement.

But what’s increasingly missing is not innovation, it’s empathy. I wish science would always remember that it treats living people, not cases, not statistics, not data. The patient is not a testing ground, but the very center of the medical act. That is where medicine begins, and that is where it should end: when the patient goes home, if not cured, at least made whole again.

A truly human science begins where efficiency ends, in the quiet, imperfect encounter between one body and another. Not in a headline, not in a breakthrough, not in a patent, but in the long pause between pain and response. Between the exhaustion of illness and the promise of science lies a fragile thread that keeps us human: not data, not speed, not certainty — but something older, and more stubborn. Hope is not a side effect. It’s the core mechanism. The final diagnostic. The thing left pulsing when everything else has gone silent.

—

Mihaela Răileanu, PhD, is a writer and a political scientist. Her work explores power, ideology, and cultural narratives through both academic research and literary storytelling. She teaches, publishes internationally, and creates interdisciplinary projects on myth, politics, and future humanity.

Notes

[1] Luiza Ilie, “Fire kills 10 at Romanian COVID-19 Hospital,” Reuters, November 14, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/fire-kills-10-romanian-covid-19-hospital-2020-11-14/; “Covid: Romania Hospital Blaze Kills at Least 10 Infected Patients,” BBC, November 14, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-54947530.

[2] “Availability of CT and MRI Units in Hospitals,” Eurostat, last modified July 2, 2021, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/ddn-20210702-2.