September 2, 2025

On Research Strikes: Lessons from Scripps Institution of Oceanography

By Jessica Ng, Cassandra Henderson, and Anjali Narayanan

This essay is part of the online edition of Organize the Lab: Theory and Practice.

THE fall 2022 University of California (UC) strike was among the first major labor actions taken by STEM graduate student researchers. Among existing accounts of the strike, however, little attention has been paid to the unique potential and challenges of striking research labor in particular.1 What does it mean for researchers to go on strike? What lessons can be drawn from this strike for other unionizing researchers?

Here we convey our experiences from the 2022 strike at Scripps Institution of Oceanography (SIO), a research-focused department with nearly 250 PhD students at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD). We analyze the strike through both our experience as current and former graduate student workers and organizers (Section 1) and a wider survey reflecting on the strike (Section 2.a). We show that collective decision-making and a strong sense of community helped sustain our strike, and we demonstrate our organizing success as it manifested in higher-than-average sustained strike participation and double the average wage concession post-strike, albeit after a long and difficult contract implementation campaign.2

We also analyze the limits of what a picket-oriented academic research strike can achieve. To address this problem, we have conducted a quantitative workers’ self-inquiry into the role of grad student research labor (Section 2.b).3 We show that research labor strikes are powerful but face several challenges, including the need for workers to understand the technical aspects of the research process well enough to strike research labor without damaging careers, identifying and supporting the minority of workers who are strategically placed to have disproportionate impact, simultaneously organizing the majority of workers who are almost entirely self-managed, and reconciling the long and sporadic timelines of research product deliveries with potentially long-lasting strikes.

Based on our analyses, we urge STEM unionists to focus on building localized groups of workers equipped with collective self-assessments and decision making, to use those collectives to power-map their labs, and to arm the collective with a plan of action derived from the material conditions of their labs.

1. The Fall 2022 SIO Strike

The SIO department offers a useful case study for conducting and analyzing an academic research strike. It bears a few distinctive characteristics:

- SIO is geographically separated from the rest of UCSD campus by a 15 minute shuttle ride or 40 minute walk up a steep hill. The physical distance meant that our engagement with the rest of UCSD was limited; as such, we developed activities, community, and strike strategy within our own department. Our isolation also insulated us from the strife that shaped strike debates elsewhere.

- Research at SIO is highly varied between and within research groups. Some labs prepare instruments and take them out to field sites or on months-long research cruises once or a few times a year before analyzing the data on a computer for the rest of the year. Some work with live biological samples; others chemically analyze ice, water, or rock samples. Some rely more on professional staff researchers than graduate students or postdocs, and they vary in the amount of research grant support.

- The department has a “woke” undercurrent within a mainstream “surfer bro” culture. A handful of workers at SIO were already involved in activism that is ideologically consistent with labor organizing: anti-racism, climate justice, tenant organizing, and solidarity with migrants and Indigenous people. Some of these activists were frustrated with the lack of engagement from our peers and focused on off-campus efforts prior to the strike.

Before the strike, a modest number of workers at SIO were active union organizers by collecting cards to form a then-new union of graduate student researchers.4 As the strike approached, the department organizing committee grew from around 5 to 15 out of 250 PhD students, and organizers started engaging coworkers in conversations about the possibility of striking. Already questions emerged which would later come to the fore: how would workers have leverage when they primarily do work for their own dissertation? How long would the strike take? As organizers, we addressed these concerns to the best of our ability, yet we did not thoroughly investigate the specifics of research labor withholding. Much of our planning instead focused on logistics: where to draw picket lines, whether the pickets would stop cars from passing altogether or just delay them, how many people would show up on the first day.5

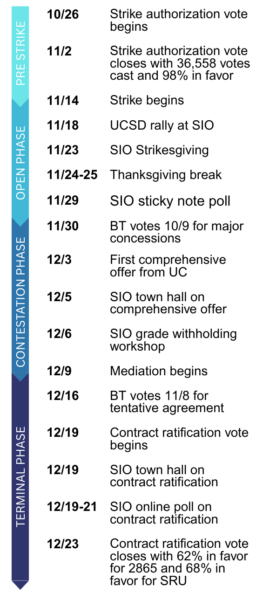

The overwhelmingly positive strike authorization vote in late October 2022 started to bring masses of SIO workers into the campus labor movement, and when the strike began on November 14, the energy was exhilarating: over a hundred SIO workers blocked all five entrances to our satellite campus on the first day. During the first few weeks of the strike, characterized as the open phase in other analyses, we focused our energy on maintaining picket lines and empowering workers beyond established organizers to take ownership of the strike.6 Every day, workers decided how many picket lines to maintain and where during morning and lunchtime huddles, and our Slack channel became a key site for coordinating activities and supplies. Workers who had never attended a union meeting picked up the megaphone to lead chants and bravely liaised with angry drivers delayed from accessing our campus coffee shop. Beyond the picket line, we attended to different interests and physical abilities with a variety of activities, including monitoring our check-in table, reaching out to remote workers, and beautifying the campus with chalk messages and art. A few days in, a “union skeptic” showed up with dozens of homemade pulled pork sandwiches for his hungry picketing coworkers. This generous act inspired us to organize daily lunches with rotating cooks and raise SIO strike lunch funds by designing and selling stickers. At the end of the first week, we hosted a large rally that drew hundreds of strikers down to SIO from the main UCSD campus. The next week, we gathered for a “Strikesgiving” sharing circle with space to learn about the university’s colonial relationship with the Kumeyaay people and for each of the 40 attendees to express their personal feelings on the strike. Through this proliferation of activities, we quickly gained experience, confidence, and a sense of community.

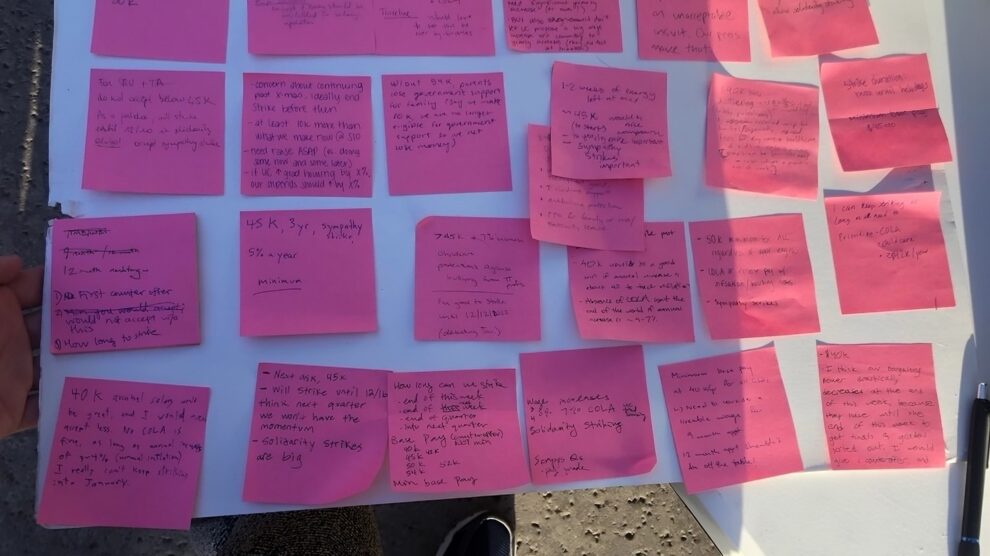

As we worked to sustain the strike, we also—crucially, in retrospect—experimented with mechanisms for internal department-level debate and decision-making. In the third week of the strike, as bargaining turned to major economic demands, the campus organizing committee prompted department stewards to evaluate what workers were most willing to fight for among the initial bargaining demands.7 At SIO, we held an impromptu discussion and poll during lunch using sticky notes, followed by a more structured but still informal poll on the SIO union Slack.8 Following this initial prompt, our daily huddles evolved from picket logistics to deeper questions of strategy and power as we connected our activity on the ground to our ability to win ambitious demands. We were developing a culture of sharing opinions openly and engaging collegially in difficult discussions about contractual demands—a practice that would soon prove essential.

Just one night after the sticky note poll, a narrow majority of our statewide bargaining team voted to drastically reduce the minimum pay demand, among other major changes from our initial position. Across the UCs, two main strike theories emerged in the ensuing contestation phase: (1) optics-based—a strategy which relied on the public perception of actions such as rallies and pickets with large physical attendance by strikers and supporters, and (2) labor-based—a strategy which emphasized the economic impact of labor-withholding over its visible manifestation.9 According to the optics-based theory, our strike was losing power as picket numbers dwindled. According to the labor-based theory, the leverage of withholding teaching and research was still growing as grading deadlines approached and missed research accumulated, and this leverage had yet to be assessed by calculating withheld grades and research deliverables.

At SIO, we debated these different conceptions of strike power during our lunchtime huddles. Some workers found the labor-withholding theory compelling and argued for withholding strategic research while continuing dissertation work to prolong the strike; others were skeptical that such a distinction could be made. While research withholding was complex, grading withholding exerted more straightforward power, and so we began to assess and map it among graduate teaching assistants. Keenly aware of the strikebreaking power of faculty to pressure their advisees, we made several attempts to solicit support from faculty, including a series of meetings, an informational session led by striking workers, individual emails to all faculty teaching classes, and an open letter.10 These efforts yielded mixed results, some partial successes, and much frustration. Robust debates over strike power and strategy across the UCs compelled our statewide bargaining team to reject the first comprehensive offer from the UC administration.

Soon after, on December 9, 2022, our bargaining team entered voluntary mediation with the university, fearing an impasse. We thus entered the terminal stage of our strike. As SIO lost strikers to exhaustion, a multi-lab research trip, and a major geoscience conference, we experimented with optics-based actions to sustain the spectacle, such as marching through campus with megaphones, blasting music outside seminars, and decorating a concrete wall with chalk messages expressing how a fair contract would improve our lives. Meanwhile, we attempted to win strike support at the geoscience conference, with the two dozen attendees disseminating buttons and displaying QR codes on their posters and presentation slides. Despite these efforts, with the holidays, finals, and grading deadlines nearing, workers at SIO were growing anxious about the possibility of continuing the strike into the new year.

On December 16, our bargaining team narrowly voted to approve a tentative agreement with the university, initiating a statewide member ratification vote. At SIO, we held a town hall over Zoom to discuss the merits and shortcomings of the tentative agreement and debated the ratification vote in our Slack channel. Many SIO workers’ assessment of the tentative agreement hinged on the interpretation of a specific clause: whether graduate student researchers would all be appointed at a standard 50% full-time equivalent, or whether they could be arbitrarily appointed at lower percentages as before, a device used by university departments to pay graduate student workers lower wages. At stake was a raise of about $8k versus a few hundred dollars. Union staff assured workers that ambiguity in the appointment clause was beneficial and that we would easily win a grievance over it. Many workers were uncertain, yet felt disempowered to contest this interpretation or fight for more concrete contractual language.11

Along with the merits of the proposed contract, workers weighed our strike power and ability to win more. We conducted an anonymous online poll based on interest expressed at the town hall to assess both of these factors. In our department of around 250 workers, we received 91 responses in two days. Of the respondents, 87% (equivalent to 32% of the department) reported withholding some amount of labor in week 6, with 36% of respondents (13% of the department) withholding all labor. While lower than the beginning of the strike, this participation was strong for a STEM department in week 6. Respondents rated our strike power at an average of 2.3 out of 5, and 42% of respondents (around 15% of the department) said they would continue withholding labor in the event of a no vote. Satisfaction with the researcher contract averaged 3.4 out of 5 and the teaching assistant contract averaged 2.9 out of 5, with 70% of respondents who had not yet voted saying they would take the majority consensus into consideration in their vote. On the whole, SIO workers felt we were losing power and were unmotivated to keep striking despite moderate dissatisfaction with the proposed contracts, while their interest in the majority consensus indicated that they valued collective assessments.12 On December 24, 2022, the statewide vote closed in favor of ratifying the tentative agreement, ending the strike.13

2.a. Strike Reflection Survey

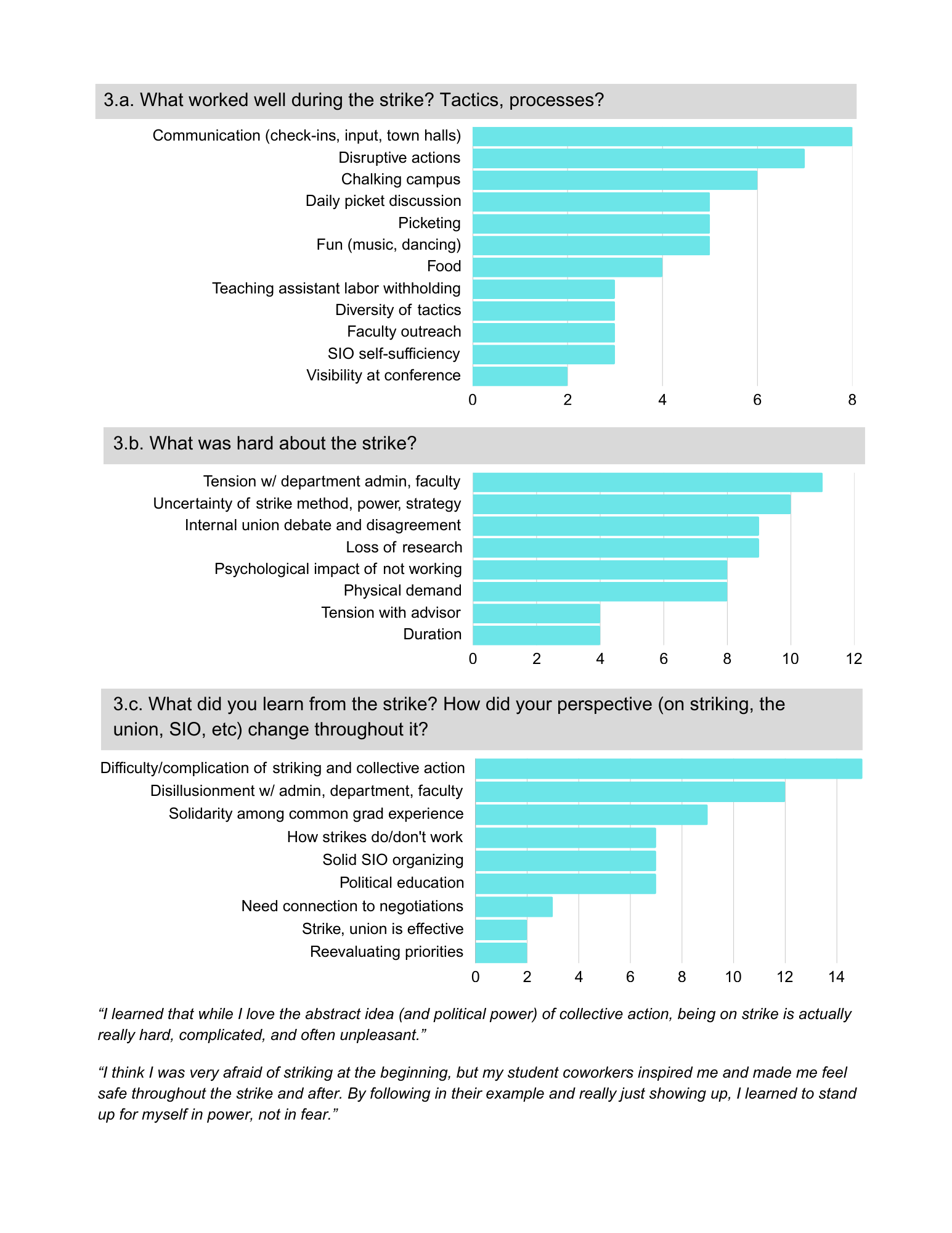

We surveyed workers on their experience of the strike six months after the strike to synthesize and document its lessons. We invited all SIO graduate student workers to respond to 10 free response questions via a Google form, with targeted outreach to dedicated strikers. We received 26 written responses and conducted an in-person interview with three participants for a total of 29 responses. We categorized the responses for each question into common themes and plotted the frequency of responses with more than one occurrence in Figure 3.

Overall, respondents thought that strike organizing at SIO was well-coordinated and built a strong sense of community. Respondents frequently praised the internal communication and deliberation within our department (8 responses, Fig. 3a), including daily lunchtime discussions, regular town halls, genuine openness to members’ input and ideas, and various feedback mechanisms such as slack polls and surveys. In contrast, some noted that union structures for participation, communication, and decision-making beyond our department were unclear, contributing to the difficulty of a contentious ratification debate. “I didn’t feel very connected to the negotiations,” said one respondent, “which is understandable, but I think making the hoi polloi feel like they’re more included in that aspect could help with keeping enthusiasm high.” Another respondent reflected, “[I] didn’t really have [a] strong opinion on the union as a whole, but for SIO, my respect for lots of my fellow students and friends went sky high. In general, I thought the SIO strike was quite organized and effective.”

Despite our organizational strength, we faced many serious challenges (Fig. 3b), with 15 respondents commenting that they learned about some difficult or complicated aspect of striking (Fig. 3c). Withholding labor—i.e., simply not working—was difficult in and of itself, with both a psychological toll (8 responses, Fig. 3b) and the material loss of research progress (9 responses). “It was very difficult to put my research on pause,” said one respondent, while another emphasized, “I love my research.” The emotional toll extended to teaching assistants: “It was really tough being a [teaching assistant] and feeling like the strike would hurt my students.” Loss of research strained relationships between graduate student workers and their faculty advisors, as 4 respondents indicated (Fig. 3b). “I ended up not getting some permits for an experiment,” said one respondent; “I think it did end up being the straw that broke the camel’s back in terms of my tumultuous relationship with my former advisor.” Besides individual advising relationships, faculty and administrators as a group were a common source of tension and disappointment (11 responses, Fig. 3b; 12 responses, Fig. 3c). One respondent said, “almost getting hit [by] professors… was pretty hard to come to terms with. I genuinely couldn’t believe the ability of these professors to not empathize since they were graduate students too.”

A few respondents noted that we were underprepared for a long-term research strike (4 responses, Fig. 3b). “Initially, I was expecting the strike to end in a few days because I believed the university would be stressed about us striking,” said one respondent, echoing the initial expectations of the authors, union leadership, and union staff. Multiple respondents remarked on the difficulty of “[k]eeping the strike spirit up” and “keeping enthusiasm high.” One noted, “I think by the end of week 2, a lot of people were showing physical and mental fatigue (as much as we didn’t want to admit it), and thinking of ways to prolong the strike got tougher and tougher as days went on.” Notably, only one respondent mentioned “potential financial insecurity” of striking this long, as the university did not withhold pay during the strike.14

The unexpected duration of the strike revealed unresolved questions of leverage and strategy. Many respondents commented on the lack of clarity on how to strike for themselves and their coworkers (10 responses, Fig. 3b). Without a robust analysis of our power and plan for how to withhold it effectively, workers were left to navigate these questions in real time on their own. One respondent revealed, “I did full withholding of labor for the first 3 weeks. Striking was mentally, emotionally, and physically exhausting, so I couldn’t do my research work during that time. So I got burnt out on striking, and went fully back to work (no striking) for the other 3 weeks.” Another respondent found “[d]ifferent expectations from different people” to be challenging: “Some students didn’t participate at all – should I be annoyed? Some thought I didn’t do enough – are they right?” The ambiguity of our strike’s strength is reflected in disparate responses to the question about lessons learned, with one noting, “I feel that academic workers are particularly poorly positioned due to the nature of our work,” while another concluded, “looking back I realized we had more power than I had thought and that the university has so many tactics for trying to keep us from using that power.” Notably, while 3 respondents mentioned that withholding teaching assistant labor was effective, no respondents brought up research labor-withholding as a tactic that worked well (Fig. 3a).

The uncertainty of whether we were strong or weak, whether we could win more or not, wore on many respondents as the strike dragged on, compounding the practical challenges of striking. “It was tough to have the uncertainty of standing out there every day and not knowing when it would end or if we would gain anything,” said one respondent. They continued, “It was stressful to have tensions so high and feeling like every decision I made was going to have some huge impact and that every decision had to be justified and balanced between competing goals.” Another respondent said, “Things weren’t moving at the table and that was a difficult moment to grasp and to accept. It produced angst for I think everyone every day. Are we getting power or are we losing power? Are we wielding it effectively or do we even have it at all?”

Reflecting on the strategic dilemmas we faced, many workers recognized the need to better understand the relationship between our research and the university. One longtime organizer raised these questions: “What exactly are we producing with our labor? How is it produced? Where, when, why and for who? What leverage do we hold and how could it be utilized? Where is the money? What is it doing? Why?” We turn to these questions in the next section.

2.b. Research Labor Survey

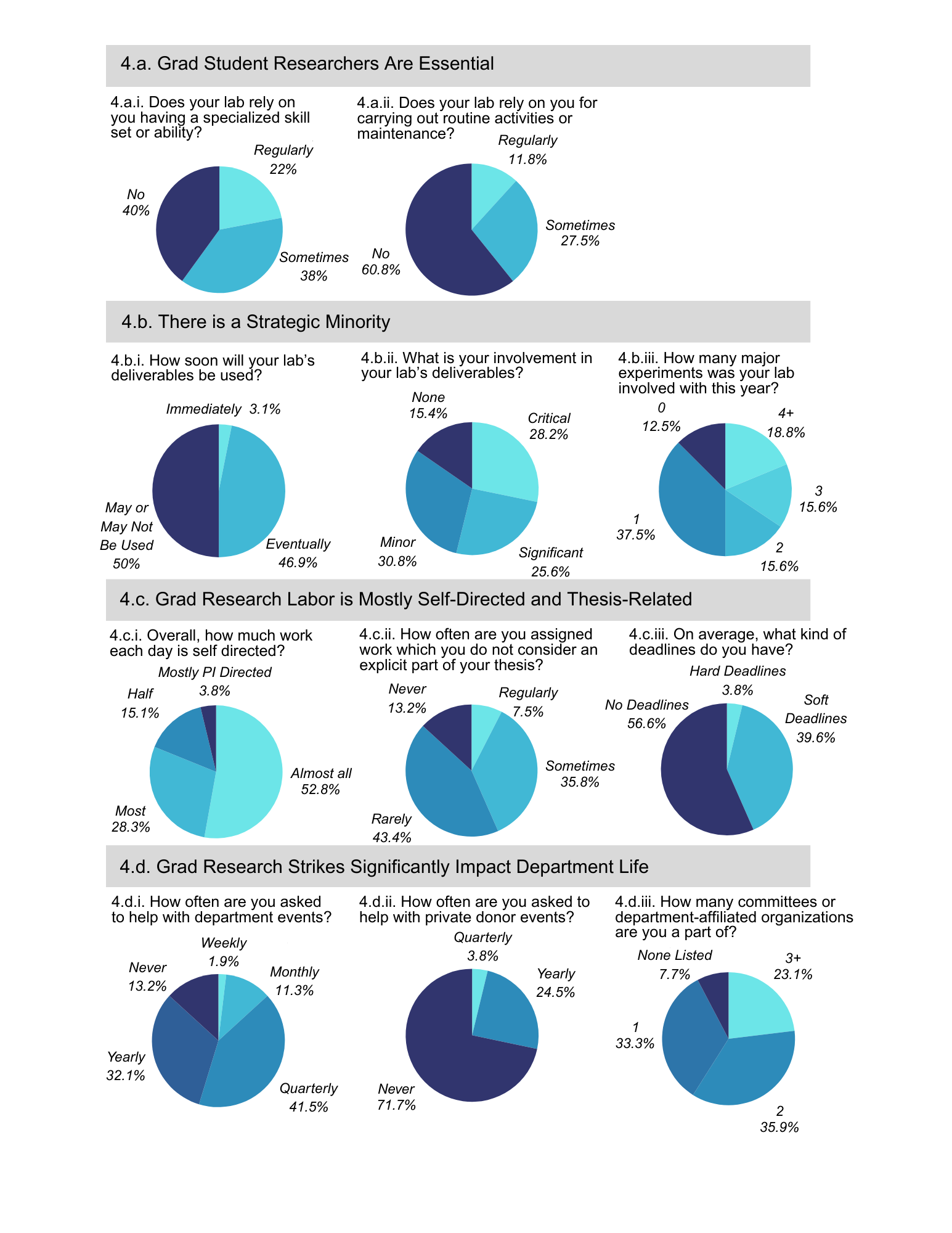

The strike raised a number of questions about research labor strikes, which we aimed to answer with a worker inquiry into how graduate student research labor functions within our department. The inquiry was based on a 34-question survey for graduate student researchers at SIO distributed via email. We contend that the 54 respondents covering all 8-program subfields in the 250-person department provide a sufficiently representative sample to draw meaningful conclusions. A summary of key results is presented in Figure 4.15

The survey shows that graduate researchers are essential to lab operations: 40% of graduate student workers we surveyed are relied on for regular lab work, and 60% have at least some specialized skills their lab needs (Fig. 4a.). A small minority of graduate workers (<10%) carry a disproportionately large amount of disruptive power (Fig. 4b.). Two statistics indicate this: first, almost all labs (nearly 90%) have major experiments yearly, ranging from one major experiment (most common) to four. These experiments can cost millions of dollars and involve dozens of personnel. As these experiments typically last days to weeks, only a few graduate students at any given time are part of labs with active experiments. Second, lab deliverables are rarely time sensitive: only 2% of grad workers surveyed are making time-sensitive deliverables, though 75% are involved in making deliverables of some kind, the majority of which are important (or at least will be used), but are not time sensitive or synchronous.

The survey also reveals a possible source of feelings of self-sabotage when striking (Fig. 4c). 80% of workers surveyed are mostly self-directed in their work. Almost all workers (>95%) are typically working on time-insensitive tasks, and a vast majority (>90%) are primarily working on thesis-related work.

Another key result is that strikes can impact department life significantly (Fig. 4d.). A majority of workers surveyed are regularly involved in department events (87%) and organizations (86%). The physical presence or absence of graduate student workers is substantial, with a majority of respondents working in offices (77%) and/or labs (25%) on campus.

Finally, almost half (45% of respondents) of graduate student workers spend weeks or months per year doing field work, mostly outside San Diego county. For SIO and similar departments, future strike planners should take note and brainstorm ways for workers to participate from the field.

3. Discussion

The laboratory is not the factory floor, and the strategic questions we face as academic workers require a theory of strike power that is specific to our labor. The above surveys provide some preliminary data towards the elaboration of such a theory. From our experience and data, we propose the following 6 strategic positions:

(1) Research strike power is wielded primarily through labor-withholding, as opposed to the symbolic power of picketing. The data presented demonstrate that graduate student researchers are essential workers, but our labor-withholding during the 2022 strike was at best irregular and certainly not strategic or targeted. Workers split time between walking the picket line and picking up precisely the most essential research labor, making sure experiments ran on time. At the same time, their primary concerns from the picket line involved doubts about the efficacy of picketing and the lack of a strike plan.

Our approach to the strike at SIO primarily focused on the logistics of picketing. During strike planning, we spent our energy deciding where picket lines would be drawn, ensuring enough people showed up, ensuring enough signs, bullhorns, snacks and activities would be there, etc. We found ourselves in strange conversations in which we tried to convince workers who said they would scab to still come out to the picket line. When numbers dwindled, organizers brainstormed new tactics to maintain the spectacle, such as marching through campus and consolidating picket lines in key areas. While this strategy maximized visible participation in the strike and helped cultivate community, it was also very energy-intensive to maintain and eventually became demoralizing as turnout dwindled. We believe labor-withholding has the potential to exert power differently, and even grow in power as the strike continues and the effects of withheld research accumulate over time. Time spent walking the line or organizing logistics could instead be used to assess what research is being withheld and to recruit more workers to withhold labor. This strategic orientation—towards labor-withholding instead of picketing—underlies the next 3 positions.

Box 1. How much was our strike worth?

Power is hard to quantify, but a dollar figure may illustrate what was “left on the table” by the picket-optics approach. The settlement of the strike left the wages promised by union staff and leadership largely unimplemented for most graduate student researchers at UCSD, including at SIO. Our raises from this 6-week-long picket-based strike were not impressive until after a grueling department-level contract enforcement campaign that took 6 months, a grievance, multiple mass protests, smaller distributed protests, and considerable repression of union activists. In the end, we succeeded in achieving a more complete implementation of the contract than other departments. The collective wages at stake in this struggle totaled an impressive $1 million per year, or about 30% raises. In comparison, the 2022 budget of SIO was close to $1 million per day. These diverging scales of both money and time suggest that an effective disruption to research on an institutional scale could constitute more effective leverage than the picket-oriented 2022 strike.

(2) Strike power is unevenly distributed based on details of the research process, often placing a select few workers in strategic positions for labor disruption. This is reflected in the data: graduate workers self-reported being essential workers in their labs, but major experiments in a given lab (e.g. field campaigns, research cruises, etc) happen only a few times a year at SIO. In some cases, a few key grad workers are responsible for critical deliverables (e.g. data, tools, reports, forecasts, etc), or one worker operates an instrument that’s critical for many others. These high-leverage workers have to weigh the impacts of labor action collective research outcomes and other workers’ careers. Such workers are frequently under tremendous pressure from their advisors to prevent potentially very costly disruptions to research; on the other hand, their coworkers in the same lab might feel virtually no pressure at all. During the 2022 strike we saw these high-leverage workers rescue their experiments, lacking sufficient practical guidance from our union on how to effectively strike this labor.

The takeaway is that unionists need to identify high-leverage workers and organize them. We suggest addressing the challenges we’ve outlined by:

- Identifying such workers via intentional power mapping well before the strike and supporting them in making a plan to strike, which may be time consuming and require technical knowledge of their work. See Table 1 for an example power mapping questionnaire.

- Supporting these high-leverage workers to disperse risk when they face pressure from faculty and lab managers. Indeed it may take an entire lab collectively deciding to strike a product or experiment before the strategic workers will feel confident doing it.

Table 1: Research Power Mapping Survey (Example from BUGWU)

- Describe your official work assignment and the labors involved.

- Besides your official tasks, what else do you do for your department or PI?

- What does the cycle of your work look like throughout the year? E.g. do you do extended fieldwork, travel for conferences during a certain season, or travel during the summer?

- What sort of impact will the withholding of your labor have on the university?

- Who else shares in this leverage? Who could undercut it if they do not withhold labor with you or even taking up your responsibilities? A postdoc? A lab scientist?

- Within your department, what grad student-involved work does the university care about the most?

- Who might retaliate against you for exerting your leverage? How?

- Who can protect you from that retaliation? How?

- What are your worst fears about striking? If that were to happen, what could we do about that collectively?

- Who can you talk to to strategize around these questions together?

(3) Whether striking is perceived as effective or “self-sabotage” depends on how the union responds to the fact that most graduate student researchers are self-directed but essential lab workers. Our data show that most workers in our department are close to 100% self-directed, working mostly on their thesis as opposed to, for example, splitting time 50/50 between their own thesis and PI-directed work for unrelated projects. As a result, workers on the picket line were very concerned that striking only affected their own progress and not the university. A worker remarked on the 2022 strike that “unlike auto workers who aren’t personally invested in whether the car is finished or not, we have the problem of privatized losses and socialised success. If your experiment fails, you’re a bad grad student, your career is over. But principal investigators (faculty) always have multiple experiments going.”

But most graduate workers are essential to their labs, and striking thesis related work is deeply impactful, causing significant financial disruption in the short term. The university’s own statements, as explained in Box 2, support this view.

Box 2. The Cost of Research Strikes to the University, According to the University

The UCSD Executive Vice Chancellor explicitly outlined the damages from the 2022 research strike in an injunction filing during the 2024 strike (emphasis added):16

19. UCSD has approximately 2000 UAW members who are Graduate Student Researchers (GSRs). These UAW members support the research of faculty and other Principal Investigators. Lack of GSR support will delay important projects, impacting research progress, UCSD’s financial outlook, and potential [sic] endanger future sources of funding. 20. The University’s School of Biological Sciences provides a good example. The approximately 100 labs rely on 185 UAW members with specific and extensive training… In invertebrate genetics, with generation times of days, experiments involve multi-generation breeding schemes that cannot be paused… UAW members in these labs cannot be replaced. If they walk off the jobs, their work would be lost… This could cost the University millions of dollars in lost resources. 21. Delay [sic] in results also risk [sic] funding sources. Many funders have only 1 to 3 deadlines per year for any given funding scheme… Delays in experiments due to UAW members withholding labor will impact the data UCSD has available to submit to these proposals. For example, faculty in UCSD’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography experienced some of the consequences outlined above during the last UAW strike in 2022 and 2023. Then, samples in the Geochemistry Facility were not processed on time due to UAW members withholding their work. This delayed research results and grant proposal submissions up to a year. 23. Faculty at the University’s Shiley Eye Institute provide additional examples of the negative effects a UAW work stoppage will have on research. Some faculty plan to use data from UAW members’ projects in the coming weeks and months for upcoming grant proposals. A strike will delay the completion of these projects by 4-12 months and place the grant funding at risk. We propose that unions put forward an orientation to striking that emphasizes: This two-part narrative can address both the holistic experience of striking (e.g. the identity of being a scientist on strike) and its immediate strategic effectiveness. (4) To address the reality that most research labor is tied to personal advancement in academia, research strike tactics should be flexible and strategic, maximizing leverage while preserving career progress. It’s not uncommon for entire PhD theses or postdoc positions to be oriented around a single experiment, whose failure would mean the lack of publishable data and potentially disastrous career prospects. We propose a two-part solution to this problem: Relatedly, preventing faculty from acting as strike-breakers is also essential for organizing labor actions at the lab level. This is surely one of the biggest hurdles to effective research strikes, and we do not have a definitive solution. We experimented with a flexible approach to research striking during the 2024 UAW 4811 Strike for Palestine.17 A research group at SIO that monitors coastal ecosystems maintains a camera system which continuously uploads images of the ecosystem to a database accessible to both members of that lab and the funding agency. This system relies on a few graduate workers to switch out the camera batteries regularly, and when someone forgot to change them out once, there was a few days’ data gap in the record where the cameras went offline. The funding agency noticed and responded with an angry email, though gaps are common (e.g., from fog). In the lead-up to the spring 2024 strike, it was discussed that a short delay (2-3 days) could be created in the battery change, after which a worker could return to work and replace the batteries. This would create a noticeable gap in the data, but not cause any serious damage to the research. In a one-on-one conversation with the worker responsible for that data, an organizer proposed that all members of the lab could take collective responsibility for the delay, using that opportunity to forward the strike demands to the funding agency itself. Ultimately this worker couldn’t be individually convinced to strike the research product, and for lack of time we did not organize a meeting of all UAW workers in the lab to make a collective decision. In retrospect, a collective deliberation with immediate coworkers could have provided greater safety and confidence for this kind of labor action. (5) Strike power is maximized with a longer strike, which is necessary due to experiments being sporadic and the products of research being used on slow timelines. Other reasons to pursue long-haul strikes are presented in “Short of the Long Haul” and demonstrated, for example, by the 2024 Dartmouth graduate workers strike.18 However, missing from these accounts are the particular reasons why longer research strikes may be more effective than short, symbolic strikes. The data presented in Section 2b demonstrate that virtually all labs have a few major experiments or collaborations each year, that most research products are not used immediately, and that graduate student workers typically provide service work to the department once per quarter to once per year. All of these point to research strikes needing time to succeed. We believe the strike duration should be derived from the power mapping—not the other way around! That is, the material conditions (the nature of particular research) should determine the timeline and tactics (extended withholding of strategic aspects of research), rather than expecting the tactics (in our case, supermajority picketing) to determine the material conditions (leverage from picket turnout), which led to myths about peak power diminishing after the first enthusiastic week. Analyzing the particulars of a department and its research practices will yield the best strike plan. As for when to strike, different groups of workers in the union have different rhythms: experiments, deliverable deadlines, grading deadlines, key instructional work. An ideal strike should activate all of them. (6) Bottom-up organizational forms—collective deliberation and a sense of community—are crucial for sustaining a long strike. Our strike was fundamentally limited by lacking a real plan for withholding labor; nevertheless, by all accounts graduate student workers at SIO punched above our weight, as demonstrated by the higher strike participation at SIO in week 6 (around 32% of the department) compared to similar departments on the same campus. We also point to strong post-strike activism, as there was enough energy, organizing infrastructure, and sense of collectivity to continue fighting in the necessary contract enforcement struggle that followed, resulting in a more fully implemented contract at SIO than comparable departments.19

We argue that this difference can be explained through the strength of the bottom-up organization at SIO. Workers attested to the importance of collective decision-making as factors that kept them out on the picket line. They spoke highly of the lunches workers brought to their picketing coworkers and the sense of departmental community and solidarity many were experiencing for the first time, which cut across groups of workers that were usually separate. They cared about what campus and statewide union leadership and staff told them—but they also cared about a department-level cost-of-living survey run by their colleagues. Near the end of the strike, workers were interested in collective self-assessments of power in deciding whether to keep striking or take a deal. Moreover, collective decision-making alleviated some of the burden of individualistic determinations of strike effectiveness and instead emphasized the importance of collective power and leverage. Importantly, practicing collectivity helps minimize the default individualistic way of thinking when it comes to research labor withholding. Questions regarding individual impact by slowing or halting thesis research or boycotting seminars ultimately only inform how one individual relates to the strike. This is in opposition to the collective way of thinking that inherently expands the scope and impact of the strike. Reflections from SIO strikers speak to the formation of a collective decision-making body with collective knowledge at the department level. The collective understands what sort of union action is possible—whether for devising particular research withholding strategies or for considering disruptive actions—better than self-appointed “organizers.” Therefore, we recommend other unionists prioritize the development of a worker collective at the level of the department or similarly local cohesive unit, a space for collective thinking and decision making involving immediate coworkers with shared working conditions. This worker collective at its core would mean that members actively engage with one another to inform, learn from, motivate, and offer support to each other before making important decisions together. In some situations, such a collective does not emerge readily. Some departments must contend with toxic cultures, and some sectors of workers such as postdocs are hindered by short-term appointments and high turnover. We encourage organizers to start by both seeding social encounters among related workers, such as coffee hours, lunches, drinks, sports teams, craft circles, and other interest groups, and conducting departmental power mapping to gain some insight into what potential collectivization of power and responsibility could look like. Demystifying the concept of collectivity with concrete and specific examples determined through power mapping can help facilitate worker-to-worker engagement and motivate collective decision-making. In the lead-up to the strike, we saw union demands cohere with prior demands from workers, including SIO-specific demands around ending anti-Black racism, economic demands by the SIO Graduate Student Council, and climate justice demands by the Green New Deal at UCSD, which had a concentration of activists at SIO. Workers involved in these projects had a diverse set of opinions on the union: some were supportive or involved, others were skeptical. But relations were generally good, and this was a huge benefit. Operating in a bottom-up fashion promoted good relations, because decisions were transparently being made by groups of known coworkers in the department who supported the prior demands, and who kept the door open for new workers to bring their concerns or criticisms, and made considerable efforts to include them proactively (e.g., through one-on-ones gathering and addressing feedback and criticism). In departments where the relationships became problematic, it was the opposite case: the union was seen as trying to supplant other groups of workers (e.g., the student government), or as unwilling to answer to them. Needless to say, a bottom-up union has much greater capacity for transparency and inclusion of other grassroots groups of workers. We have analyzed our experiences of the 2022 UC-UAW strike at Scripps Institution of Oceanography with a strike reflection survey and research labor survey. From this, we proposed six strategic positions: Our strike made significant gains for workers at SIO. In fact, after an additional year of hellish contract enforcement struggles, the raises we won reversed nearly two decades of inflation and cost of living increases.20 However, the general trend of academic labor is towards more precarity and fewer job prospects, intensified under the current federal administration. In this historic moment, it is imperative that labor organizers in every industry—including academic research—improve our theory and practice. ♦ “A friend later told me (with regards to research and work), “it feels so insignificant”, and it’s really stuck with me. I think at one point I felt that too during our strike. The research that I was missing out on doing or the paper that was delayed, it all seemed so insignificant when compared to fighting against the UC to ensure we can afford basic needs while being in academia.” “I truly believe this is just the beginning of the labor movement in academia and because it is the beginning, I don’t think people can visualize the effects our efforts and movements will have on future academic workers and how this can incite a shift in the culture of academia.” We are grateful to our SIO comrades, with special thanks to Cody P for helping with the strike reflection survey analysis and Will S for helping develop and distribute the labor survey, as well as all survey respondents and those who joined us on the picket line in 2022 and 2024. The Scripps Graduate Student Council was instrumental in cohereing departmental solidarity and establishing a precedent of inquiry with its cost of living survey, as well as in distributing the research labor survey. Many UAW comrades contributed to survey design outside SIO, including Ray M, Conor O, Alex W, Rohan S, Patrick Y and Kate M. We are proud members and alumni of UAW 4811 (formerly SRU-UAW). We also thank our comrades who gave us feedback on an early draft of this piece, including Isabel K, Jack D, Charlotte B, and Hayden J. Finally we thank the editorial team at Science for the People, especially Gabriel W and Calvin W. Jessica Ng is a postdoc at Princeton University, member of PUPS-UAW, and paleoclimatologist turned interdisciplinary environmental studies scholar studying the impacts of lithium mining. Cassandra Henderson is a postdoc at the University of Washington, member of UAW-4121, and coastal physical oceanographer studying infragravity. Anjali Narayanan is a graduate student researcher at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego, member of UAW-4811, and bio-optical oceanographer studying the response of Arctic phytoplankton to climate change.

Box 3. Example of a Strategic Research Strike

Box 4. The Popular Front at SIO

Conclusions

Acknowledgements

—

Notes

.