March 29, 2021

“Art for all! Science for all! Bread for all!”

Remembering Louise Michel on the 150th Anniversary of the Paris Commune

By Cliff Conner and Erik Wallenberg

150 years ago, on March 18, 1871, the poor and working class of Paris — referred to dismissively by contemporary French officialdom as “the vile multitude” — rose in rebellion. They disarmed the existing national guard and armed the citizens of the city instead. By March 28 they had raised the red flag over the city, declared Paris a Commune, elected a citywide government, and created a new 200,000-strong democratically-organized Parisian National Guard. They outlawed the death penalty and military conscription, and sent delegates to other cities to help establish similar governments of the people throughout France.

It was a revolt of a historically unprecedented character, which although unable to consolidate its revolutionary accomplishments, left behind an extremely rich legacy. As the first example in history of a working-class movement taking power, the Paris Commune was an inspiration for the great socialist revolutions of the twentieth century.

The Commune’s experiment in working class rule with no mayor or higher officials — just elected bodies — was recognized then and still today as a glimmer of how a different world might be organized.1 The Parisian workers movement of 1871 showed an awareness that the workers constituted a distinct social class with interests different from and opposed to the interests of the ruling capitalist class. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels hailed the Commune as the latest innovation in workers’ control, and working class movements have looked to the Paris Commune as an example to follow ever since.2

The social crisis that produced the Paris Commune grew out of a war between France and Prussia. In August 1870, the foolhardy Emperor Napoleon III ordered the French army to invade. On September 2, the emperor himself was captured, along with 100,000 French troops, by Bismarck’s army. His abject surrender opened the door to an invasion of France by the armies of the Prussian-led German Empire.

French resistance coalesced around a provisional “Government of National Defense” headed by Adolphe Thiers and other liberal republican opponents of the disgraced Emperor, but they proved lacking in the will to resist the German onslaught. The Paris Commune arose, first of all, to defend Paris — and by extension all of France — from Bismarck’s occupying army.

The Germans besieged Paris but failed to subdue the city. When the Paris Commune made clear its intention to continue the struggle for national independence, Thiers and Bismarck collaborated to crush the Commune. The French army had been greatly weakened by the conflict with the Germans, who held large numbers of surrendered French troops as prisoners. So Bismarck turned the imprisoned French troops over to Thiers, who immediately sent them to attack Paris.

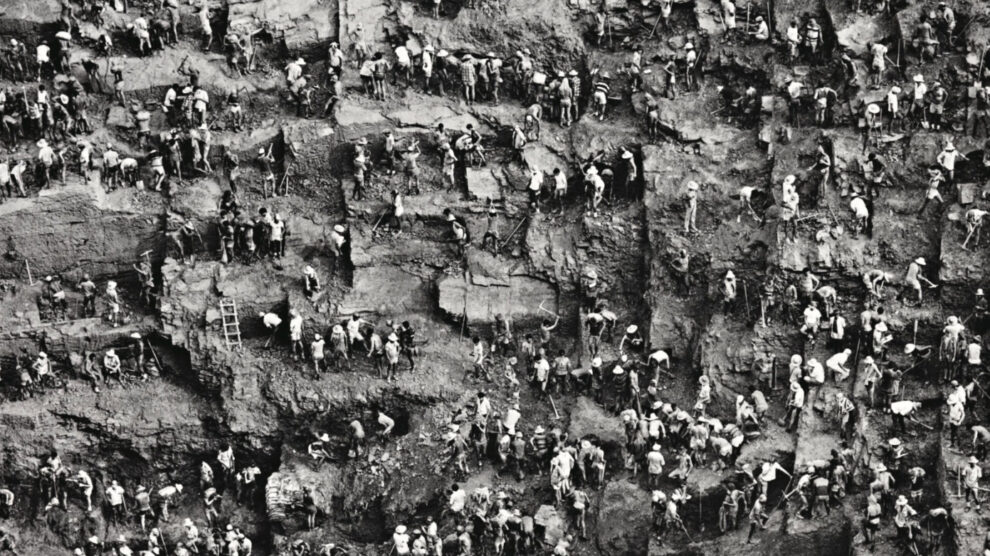

The Paris Commune withstood attacks from the Germans and the French ruling class for more than two months. Although the working men and women of Paris acquitted themselves with courage, dignity, and honor, they were butchered by French troops under the political and military command of odoriferous villains such as Adolphe Thiers and General Marquis Gallifet.

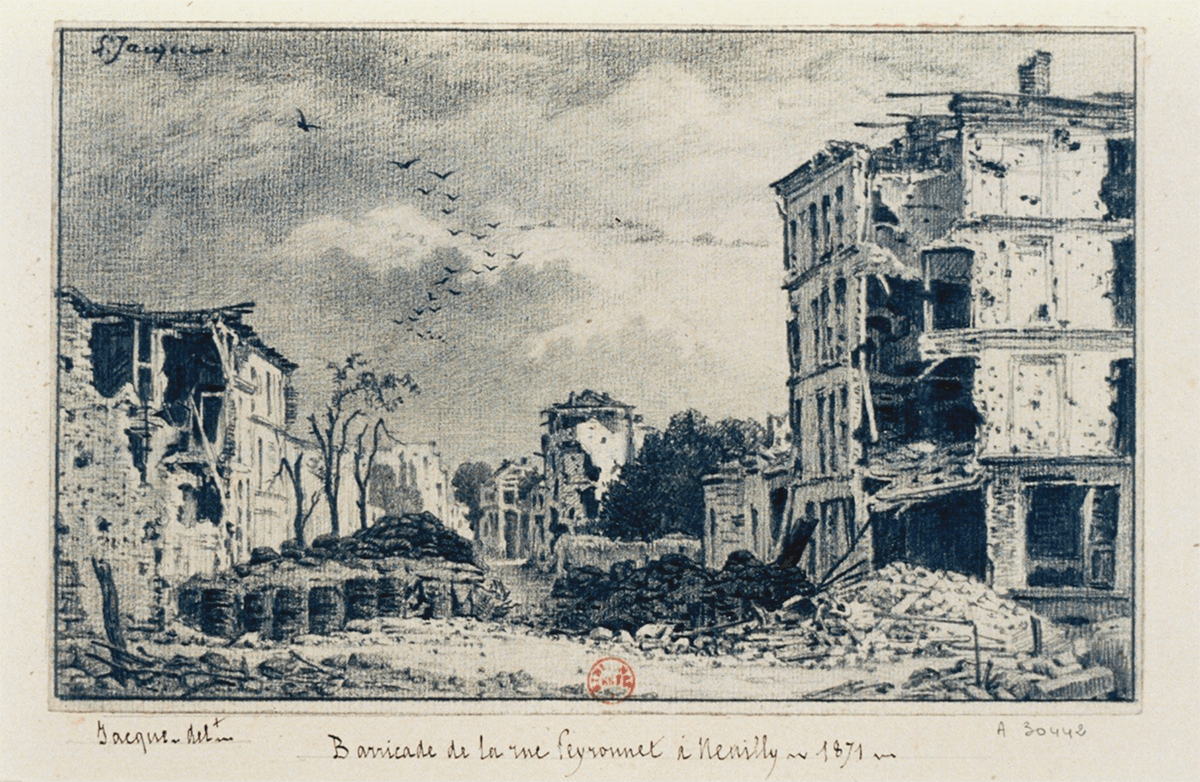

The Parisians did not back down, even when their assailants wore French uniforms. Thiers’ army broke through the city’s external defenses and entered Paris on May 21, 1871. The National Guard and Parisian civilians, men and women alike, fought courageously arrondissement by arrondissement and block by block, but eventually they were overwhelmed by superior military power and were forced to put down their arms. According to the ordinary rules of war of post-Enlightenment Europe, the disarmed combatants should have been accorded humane treatment, but the “republican” Thiers and his rightwing royalist allies instead unleashed a furious, vindictive massacre of the defenseless Parisian populace. An estimated 30,000 men, women, and children were cruelly slaughtered throughout the city over the ensuing days.

Louise Michel was one of the Commune’s most outstanding leaders. She was a member of the Vigilance Committee, a fierce fighter on the barricades, a spokeswoman for the uprising, and wrote extensively about her experience. Her memoir, The Red Virgin, written during several terms of imprisonment after the Commune’s defeat, provides an in-depth look into her life and political ideas. The title, at once a radical political and religious reference, casts Louise Michel as the mother of the Paris uprising, of anarchism and socialism, and of radical politics more generally. And at the same time, this name given to her by her admirers and collaborators was meant to claim her as a hero, a saint even, of the uprising.

This excerpt begins with her adolescent identification with tortured and mistreated animals. Michel shows us both how this imbued her with a desire to save them and to stop their suffering, and also helped her see the larger suffering of people in the world, in this case the peasants of the French countryside. Specifically, Michel notes how her opposition to the death penalty was born of witnessing the beheading of a goose. And while she shows great contempt for those people who are cruel to animals, she also identifies the way these same people are cruelly treated as the origin and reason for their callous abuse of their fellow creatures.

Animal cruelty in the brutality of factory farms and slaughterhouses has grown to a gargantuan scale since Louise Michel’s era. Beyond the mistreatment of animals for slaughter for food, or simply out of carelessness, Michel also called for an end to needless and inhumane experimentation on animals in the name of science. These cruelties continue today and remain driven by the same profit imperatives Michel discussed in her writing. While she was hopeful, certain even, that in the near future food would be available for all, we of course know that while scientific practices and advances might have made this possible, the economic and political system has squelched the possibility. In many ways, her insights are still valid in a world far from having reached the equality and justice she fought for.

Finally, beyond the plentitude of food made possible by science, Michel connects this call for a science to serve humanity with a call for a world where art is treated the same way. The world she is fighting for is a world where genius “will be developed, not snuffed out.”3 To her, “the privilege of knowledge is worse than the privilege of wealth,” and access to the arts is “a part of human rights.” On this, the 150th anniversary of the founding of the Paris Commune, we celebrate the life of Louise Michel, a fighter for a world where food, art, and science are for all, and for the good of all.

Excerpt from “Chapter 4: The Making of a Revolutionary” from the Memoirs of Louise Michel, The Red Virgin

Above everything else I am taken by the Revolution.4 It had to be that way. The wind that blew through the ruin where I was born, the old people who brought me up, the solitude and freedom of my childhood, the legends of the Haute-Marne, the scraps of knowledge gleaned from here and there — all that opened my ear to every harmony, my spirit to every illumination, my heart to both love and hate.5

Everything intermingled in a single song, a single dream, a single love: the Revolution.

As far back as I can remember, the origin of my revolt against the powerful was my horror at the tortures inflicted on animals. I used to wish animals could get revenge, that the dog could bite the man who was mercilessly beating him, that the horse bleeding under the whip could throw off the man tormenting him. But mute animals always submit to their fate.

In the Haute-Marne, the brooks and the lush fields shaded with willows are filled with frogs during summer. You can hear them in the beautiful evenings, sometimes an entire choir.

The peasants cut frogs in two, leaving the front part to creep along in the sun, eyes horribly popping out, front legs trembling as they try to flee under the ground. Able neither to live nor to die, the poor beasts try to bury themselves beneath the dust or mud. In the bright sunlight their soft, enormous eyes shine with reproach.

And geese being fattened: The peasants nail a goose’s webbed feet to the floor to keep it from moving around. Or horses, which men gore with bulls’ horns. Animals always submit, and the more ferocious a man is toward animals, the more that man cringes before the people who dominate him.

The peasants give little animals and birds to their children for playthings. In spring on the thresholds of peasants’ cottages you can see poor little birds opening their beaks to two or three-year-old urchins who stuff them innocently with dirt. They hold up fledglings by a foot to watch them flap little featherless wings trying to fly, or they drag puppies or kittens like wagons over stones and through brooks. When the beast bites the child, the father crushes it under his shoe.

When I was a child I saved many an animal. They filled up the crumbling Tomb, but it didn’t matter if I added another to the menagerie.6 At first I traded things with other children to get the nests of nightingales or linnets, but then the children came to understand that I raised the little creatures. Children are less cruel than people think; people just don’t bother to make them understand.

And then there are dogs and cats that have grown too old: I have seen them thrown live into crayfish holes. If the woman who was throwing the beasts in had fallen into the hole herself, I wouldn’t have reached out my hand to pull her out.

All of this happens without anyone really thinking about it. Labor crushes the parents; their fate grips them the way their child grips an animal. All around the globe people moan at the machine they are caught in, and everywhere the strong overwhelm the weak.

The dominant idea of an entire life can come from some random impression. When I was very small, I saw a decapitated goose. I was very little, I know, because I remember Nanette holding me by the hand to cross the hall.7 The goose was walking about stiffly, and where its head had been its neck was a bruised and bloody wound. It was a white goose with its feathers spattered with blood, and it walked like a drunkard while its head, thrown into a corner, lay on the floor with its eyes closed.

The sight of the headless goose had many consequences. One result was that the sight of meat thereafter nauseated me until I was eight or ten, and I needed a strong will and my grandmother’s arguments to overcome that nausea. The impression of the headless goose lies at the base of my pity for animals, and it also lies at the base of my horror at the death penalty. Some years after I saw the headless goose, a parricide was guillotined in a neighboring village, and at the time he was to die, the sensation of horror I felt for the man’s anguish was mixed with my remembrance of the goose’s torment.

The impression I had gotten from seeing the decapitated goose was kept vivid by stories of sufferings I heard at écrègnes. During the long winter evenings of the Haute-Marne, the women of each village met in a special house set aside for them known as the écrègnes. In their sessions, also called écrègnes, they would spin and knit and tell old stories like those about the Ghost-in-Flames, who dances through the fields in his fiery robe, and gossip about what was going on in various peoples’ homes…

My evenings at the village écrègnes added to the feeling of revolt that I have felt time and time again. The peasants sow and harvest the grain, but they do not always have bread. One woman told me how during a bad year — that is what they call a year when the monopolists starve the country — neither she, nor her husband, nor their four children were able to eat every day. Owning only the clothes on their backs, they had nothing more to sell. Merchants who had grain gave them no more credit, not even a few oats to make a little bread, and two of their children died — from hunger, they thought.

“You have to submit,” she said to me. “Everybody can’t eat bread every day.”

Her husband had wanted to kill the man who had refused them credit at 100 percent interest while their children were dying, but she stopped him. The two children who managed to survive went to work ultimately for the man whom her husband wanted to kill. The usurer hardly gave them any wages, but poor people, she said, “should submit to that which they cannot prevent.”

Her manner was calm when she told me that story. I had gone hot-eyed with rage, and I said to her, “You should have let your husband do what he wanted to do. He was right.”

I could imagine the poor little ones dying of hunger. She had made that picture of misery so distressing that I could feel it myself. I saw the husband in his torn shirt, his wooden shoes chafing his bare feet, going to beg at the evil usurer’s and returning sadly over the frozen roads with nothing. I saw him shaking his fists threateningly when his little ones were lying dead on a handful of straw. I saw his wife stopping him from avenging his own children and others. I saw the two surviving children growing up with this memory, and then going off to work for that man: the cowards.

I thought that if that usurer had come into the écrègnes at that moment I would have leaped at his throat to bite it, and I told her that. I was indignant at her believing everybody couldn’t have food every day. Such stupidity bewildered me.

“You mustn’t talk like that, little one,” the woman said. “It makes God cry.”

Have you ever seen sheep lift their throats to the knife? That woman had the mind of a ewe…

Meanwhile, the family property was bringing in so little that neither we nor my uncle, who cultivated half of it, was succeeding in making ends meet. Many similar years would follow, I felt. People couldn’t always help others, and indeed something more than charity was necessary if each person was always to have something to eat. As for the rich, I had little respect for them.

I know the full reality of heavy work on the land. I know the woes of the peasant. He is incessantly bent over land that is as harsh as a stepmother. For his labor all he gets is leftovers from his master, and he can get even less comfort from thought and dreams than we can. Heavy work bends both men and oxen over the furrows, keeping the slaughterhouse for worn-out beasts and the beggar’s sack for worn-out humans.

The land. That word is at the very bottom of my life. It was in the thick, illustrated Roman history from which my whole family on both sides had learned how to read. My grandmother had taught me to read from it, pointing out the letters with her large knitting needle. Reared in the country, I understood the agrarian revolts of old Rome, and I shed many tears on the pages of that book. The death of the Greeks oppressed me then as much as the gallows of Russia did later.

How misleading are the Georgics and Eclogues about the happiness of the fields.8 The descriptions of nature are true, but the description of the happiness of workers in the fields is a lie. People who know no better gaze at the flowers of the fields and the beautiful fresh grass and believe that the children who watch over the livestock play there. The little ones want grass only to stretch out in and sleep a little at noon. The shadow of the woods, the yellowing crops that the wind moves like waves — the peasant is too tired to find them beautiful. His work is heavy, his day is long, but he resigns himself, he always resigns himself, for his will is broken. Man is overworked like a beast. He is half dead and works for his exploiter without thinking. No peasants get rich by working the land; they only make money for people who already have too much.

Many men have told me, in words that echoed what the woman told me at the écrègne: “You must not say that, little one. It offends God.” That’s what they said to me when I told them that everyone has a right to everything there is on earth.

My pity for everything that suffers — more perhaps for the silent beast than for man — went far, and my revolt against social inequalities went still further. It grew, and it has continued to grow, through the battles and across the carnage. It dominates my grief, and it dominates my life. There was no way that I could have stopped myself from throwing my life to the Revolution.

I have often been accused of having more solicitude for animals than for people. It is certainly true that a sadness takes hold of me when men must destroy a beast to whom mercy cannot be shown without endangering others. You hold in your hands a being that wishes to live.

Once, near where I lived, on the hill down which vineyards sloped, men had surrounded a poor she-wolf that howled as she tried to hide her little ones within her paws. I begged mercy for her, but naturally it wasn’t granted.

The mercy that as a child I asked for the wolf, I wouldn’t ask now for the men who behave worse than wolves toward the human race. Whatever the pity that wrings the heart, harmful beings must disappear. At the death of those who, like the Russian czars, represent the slavery and death of a nation, I would now have no more emotion than I would have about removing a dangerous trap from the road. Such persons can be struck down without remorse. If the opportunity arose, I would always feel that way, as I did yesterday, as I will tomorrow.

I was accused of allowing my concern for animals to outweigh the problems of humans at the Perronnet barricade at Neuilly during the Commune, when I ran to help a cat in peril.9 I did that, yes, but I did not abandon my duty. The unfortunate beast was crouched in a corner that was being scoured by shells, and it was crying out like a human being. I went to find him, and it didn’t take a minute. I put him more or less in safety, and later someone even picked him up.

Another incident happened more recently. Some mice had appeared in my cell at Clermont. I had a pile of wool coverings my mother and friends had sent me, and I immediately used them to stuff up all the mouseholes. From behind one of my makeshift plugs during the night, however, I heard a poor little cry, a cry so plaintive that it would have taken a heart of stone not to open up the blocked hole. So I did, and the beast came out.

The mouse was either imprudent or a genius in knowing how to judge her world. From that moment on she came boldly up on my bed, carrying morsels of bread. She made fun of the gestures I made to get her to leave, and she used the underside of my pillow as a pantry and even worse.

She wasn’t in my cell when I was taken away, so I wasn’t able to put her in my pocket. I asked my neighbors in nearby cells to care for her, but I don’t know what happened to the poor beast.

Why should I be so sad over brutes, when reasoning beings are so unhappy? The answer is that everything fits together, from the bird whose brood is crushed to the humans whose nests are destroyed by war. The beast dies of hunger in his hole; man dies of it far away from his home. A beast’s heart is like a human heart, its brain like a human brain. It feels and understands. The heat and spark will always rise up. It can’t be crushed out.

Even in a gutter like a laboratory, a beast is sensitive both to caresses and to brutalities. More often it feels brutalities. People find it interesting to torture a poor animal to study mechanisms which are already well known and which fresh tortures cannot make known any better, because the pain being inflicted causes the animal’s organs to function abnormally. When one of its sides is dug into, someone turns it over to dig into the other. Sometimes, in spite of the bonds that immobilize it, the animal in its pain moves the delicate flesh on which someone is working. Then a threat or a blow teaches it that man is the king of animals. I have heard that during an eloquent demonstration a professor stuck his scalpel into the living animal as he would have into a pincushion, because he couldn’t gesture holding the scalpel in his hand. The animal was already being sacrificed, so additional pain made little difference. At Alfort, people did sixty-some operations on the same horse, operations that did no good, but made the beast suffer as it stood there trembling on its bloody hooves with their torn-off shoes.

All this useless suffering perpetrated in the name of science must end. It is as barren as the blood of the little children whose throats were cut by Gilles de Retz and other madmen at the beginning of modern chemistry.10 Ultimately, a science, not gold, came out of their crucibles and their search for the philosopher’s stone, but science came from the nature of the elements and not from the cruelties of experimenters.

New wonders will come from science, and change must come. Time raises up volcanoes under old continents, and time allows new feelings to grow. Soon there will be neither cruelty nor exploitation, and science will provide all humanity with enough food, with nourishing food.

I dream of the time when science will give everyone enough to eat. Instead of the putrefied flesh which we are accustomed to eating, perhaps science will give us chemical mixtures containing more iron and nutrients than the blood and meat we now absorb. The first bite might not flatter the palate as much as the food we now eat, but it will not be trichinated or rotten, and it will build stronger and purer bodies for men weakened by generations of famine or the excesses of their ancestors.

With the abundance of nourishing food in that future world, there must be art, too. In that coming era, the arts will be for everyone. The power of harmonious colors, the grandeur of sculpted marble — they will belong to the entire human race. Genius will be developed, not snuffed out. Ignorance has done enough harm. The privilege of knowledge is worse than the privilege of wealth. The arts are a part of human rights, and everybody needs them.

Neither music, nor marble, nor color, can by itself proclaim the Marseillaise of the new world. Who will sing out the Marseillaise of art? Who will tell of the thirst for knowledge, of the ecstasy of musical harmonies, of marble made flesh, of canvas palpitating like life? Art, like science and liberty, must be no less available than food.

Everyone must take up a torch to let the coming era walk in light. Art for all! Science for all! Bread for all!

—

Clifford D. Conner taught history of science at the School of Professional Studies, CUNY Graduate Center. He is the author of The Tragedy of American Science (Haymarket Books, 2020), A People’s History of Science (Bold Type Books, 2005), and Jean Paul Marat: Tribune of the French Revolution (Pluto Press, 2012).

Erik Wallenberg is a PhD candidate in the History Program at CUNY Graduate Center. His research is focused on the portrayal of environmental crises, politics, and science in activist theater. He has taught classes in environmental history, global history, and environmental justice at Brooklyn College and the University of Vermont and is Acquisitions Editor at Science for the People.

References

- A major weakness of the Commune’s revolutionary legacy was the exclusion of women from its elected leadership. Women could not vote or hold office. That did not, however, prevent women from playing crucial de facto leadership roles, or Louise Michel from becoming the Commune’s most iconic leader.

- In retrospect, the leadership of the Paris Commune is often associated with Marxism, but in fact Marxists were a distinct minority within it. Among the Commune’s leaders, including Louise Michel, far more were admirers of Louis-Auguste Blanqui, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, and Mikhail Bakunin than were partisans of Karl Marx.

- Nearly 100 years later, evolutionary biologist and Science for the People member Dr. Stephen Jay Gould uttered a similar sentiment: “I am, somehow, less interested in the weight and convolutions of Einstein’s brain than in the near certainty that people of equal talent have lived and died in cotton fields and sweatshops.”

- Translation from The Anarchist Library. Translated by Bullitt Lowry and Elizabeth Ellington Gunter. https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/louise-michel-the-red-virgin?v=1563328039#toc5. Footnotes added by Cliff Conner and Erik Wallenberg for clarity and context.

- The Haute-Marne is the department in northeastern France where Louise Michel was born and grew up.

- Tomb is Michel’s nickname for the half-ruined manor house where she had grown up: “the ruin where I was born.”

- Nanette was one of two close childhood friends whom Michel describes as “two remarkably intelligent young women who had never left the district.” She deliberately avoids giving the family names “of persons whom I lost sight of long ago, to spare them the disagreeable surprise of being accused of conniving with revolutionaries.”

- Georgics and Eclogues: Poems about rural life by the Roman poet Virgil.

- The Commune’s defenders built many barricades to slow their enemies’ advance. This one blocked rue Perronet in Neuilly-sur-Seine in Paris’s 17th arrondissement.

- a.k.a. Gilles de Rais, also, “the original Bluebeard,” a fifteenth-century French alchemist tried and convicted of Satanism and murdering children.