Under the Influence of Lewontin: Volume One

A Collage of Reflections

July 23, 2021

Friends and colleagues of Dick Lewontin are sharing their stories and reflections. Contact us to include your tribute in the Lewontin Memorial Collection.

Contents

The NYT Does It Again —John Vandemeer

The Mystery of Isadore Nabi —Dick Clapp

Too Esoteric for Dick —Michael Friedman

Third Time’s the Charm —Stuart Newman

Thank You, Dick —Vinton Thompson

Just Another Human —Alan Goodman

The NYT Does It Again

John Vandemeer

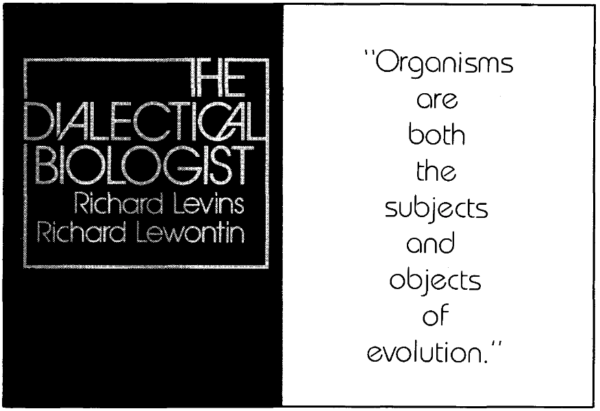

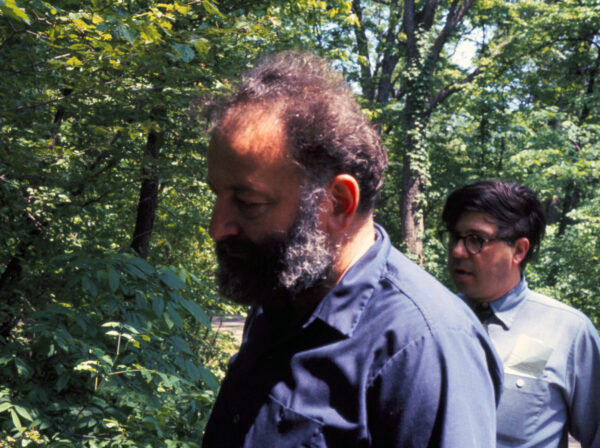

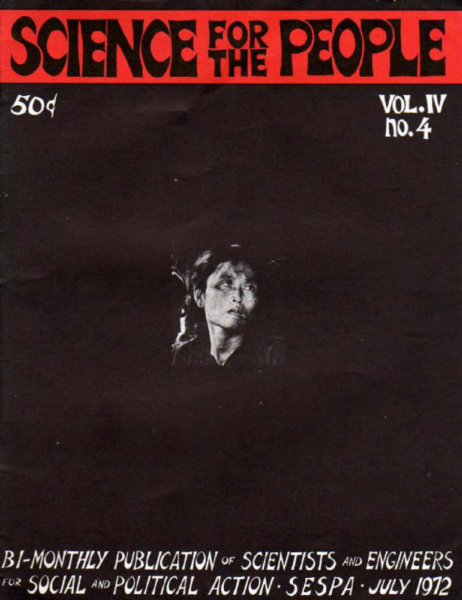

In light of The New York Times omitting some of Dick’s really important contributions, especially regarding the political aspects of his work (and simply ignoring his long association with Dick Levins), it seems to me that Science for the People magazine ought to take up the slack here. Lewontin was the one who detailed the lies of the agricultural research establishment regarding the inbred/hybrid method of corn “improvement.” He was a long-standing opponent of the industrial agricultural system, a long term member of both Science for the People and the New World Agriculture and Ecology Group, an active participant in Science for Vietnam, and contributed vital support to the Black Panthers in Chicago. Much of all that political activity was in conjunction with Dick Levins, who I would argue was a major influence on him. Their book, The Dialectical Biologist, is still a classic; and their hilarious “collaboration” with Isadore Nabi reflects something of their commitment to fun, even when doing science or politics.

The Mystery of Isadore Nabi

Dick Clapp

In the March/April 1986 Issue of the Science for the People magazine, Michael Filisky reviewed Dick Lewontin and Dick Levins’s book The Dialectical Biologist. Here is an excerpt:

“On Analysis” contains both the heaviest and the lightest reading in the book. One essay, ‘Dialectics and Reductionism in Ecology,’ includes pages of equations that sent me back to my textbooks. . . . As a reward for working through this essay, the reader can enjoy “Isadore Nabi on the Tendencies of Motion,” which is both a parody of a turgid scientific paper (conclusions: plants grow up, apples fall down, London is sinking, and drowning men move upward 3/7 of the time and downward 4/7 of the time); and an exchange of letters to the editor of Nature questioning the identity of the paper’s author, one Isadore Nabi. Is this really a pseudonym for Lewontin and others, or, as listed on page 3165 of American Men and Women of Science, a distinguished scientist from someplace called Cochabamba University?

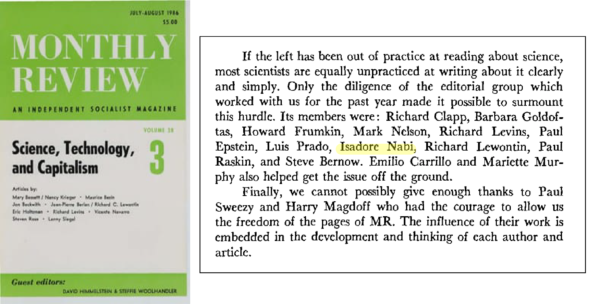

Later that year, Monthly Review published a special issue titled “Science, Technology and Capitalism” that was assembled by an editorial group that included Dick Lewontin, Dick Levins, and several others, including me. One of the articles in the Monthly Review special issue was by Lewontin and a co-author on the topic of hybrid corn; another was by Levins on the need for “a science of our own.” The editorial group was called together by David Himmelstein and Steffie Woolhandler, who was also on the editorial board of Science for the People at the time. According to the introduction, the editorial group also included Isadore Nabi, although I can attest that there was no such person in our meetings. It was a way of continuing the clever ruse that Lewontin and Levins had begun in their book published the previous year. So, although they were prodigious intellectuals, they both had a playful sense of humor. I considered it a deep privilege to have known and learned from them over the years.

Too Esoteric for Dick

Michael Friedman

I was sad to hear of Richard’s passing. Together with Dick Levins and Steve Gould (both of whom I knew considerably better), he inspired me to go back for graduate studies in evolutionary biology and really deepened my understanding of the political nature of science. I had read some of their work back in the early 70s, when I encountered the magazines of the old Science for the People in a student organization office. I initially met the three of them through my work in Nicaragua in the 1980s and then as staff coordinator for the New York Brecht Forum, of which all three were on the advisory board. Most recently, I discussed the esoteric concept of bacterial “species” with Richard in a couple of emails. He basically scratched his head… He will be missed!

Third Time’s the Charm

Stuart Newman

(Except reproduced from the Center for Genetics and Society with permission)

Although my first two encounters with Dick were at a distance, we wound up in the same department at the University of Chicago, when as a postdoctoral fellow I moved from chemistry to theoretical biology and was drawn into the emerging field of complex systems biology that Dick was helping to forge. We also worked together to organize the University of Chicago chapter of Science for the People, joined in this by Dick Levins, the anatomists Michael Goldberger, Marion Murray, and Len Radinsky, and the mathematician Mel Rothenberg.

We also wound up, by almost pure coincidence, at the same department during the same year at University of Sussex in the UK, Dick as a sabbatical visitor and me as a visiting research associate. There we and our families, Americans abroad, became close friends. Notwithstanding our differences in age and accomplishments, Dick took me on as a colleague and comrade, serving as a model for a life as a scientist-activist to which I continue to aspire. His death on July 4, which followed by three days that of his wife of 73 years Mary Jane, is a personal loss, and one that leaves an empty space in world science.

Thank You, Dick

Vinton Thompson

Ironically, it was E. O. Wilson who first sent me to Dick Lewontin. I waylaid Wilson senior year at Harvard, asking where I could best become an evolutionary biologist, a field to which his undergraduate course had recruited me. He told me to go to the University of Chicago, where Lewontin was creating a terrific program. Dick, he observed, would grab you by the tie and not let go in his enthusiasm. So, with concurring opinions from Steve Gould (my advisor) and Ernst Mayr, I was off to Chicago, slightly delayed by an application held hostage in a student-occupied administration building.

I arrived in fall 1969. Dick Lewontin had brought Dick Levins, a Columbia grad school colleague, to Chicago, rescuing Levins from a de facto blacklist exile in Puerto Rico. Together they anchored a wonderful introductory series in population biology. They were both, in their individual ways, gifted lecturers. Great ecologists like Monte Lloyd and Dan Janzen rounded out the syllabus. It was intellectually exciting. Lewontin, with his colleague Jack Hubby, was publishing his path-breaking molecular measurements of genetic diversity, making for a population biology golden age, at least from my perspective.

But, by this time, the ongoing Vietnam War loomed over everything. Dick Lewontin was not only a brilliant scientist, he was a committed social activist. He and Dick Levins were the faculty glue for a developing Science for the People chapter, which included grad and undergrad students and some people with no direct university affiliation. Dick was fearless. He not only resigned from the National Academy of Sciences to protest complicity in the war effort, he also announced that our Science for the People group would give scientific aid to the Vietnamese, a program that became the Science for Vietnam Project. Needless to say, public commitment by American scientists to give support to the other side got a lot of press, and a lot of FBI attention.

In the midst of this, I was an impoverished grad student with a life to lead. Though he was not my advisor, Dick gave me critical help and support, a testament to a part of his character that was not on public display. First, he helped me get resources to set up my thesis project. I never met the eminent population geneticist Theodosius Dobzhansky in person, but I was in the room when Dick called him to ask if I might get some materials one of Dobzhansky’s students had used. Later, when my initial three-year graduate fellowship expired, Dick came up with Ford Foundation money to carry my last two years. When I went on the job market, Dick, by then at Harvard, wrote letters of recommendation. When I needed a sabbatical placement to finish projects for tenure at a teaching university, Dick hosted me for eight months at his lab in the Museum of Comparative Zoology. Later, when I became president of a small minority-serving college, Dick gave unsolicited contributions to help the cause.

Dick was unforgettable: really smart, combative, very generous, supportive at critical moments, a fighter for all the right causes. Two last reminiscences: He was on my oral prelim exam committee, the gateway to being allowed to proceed with a PhD thesis. In that somewhat formal and definitely stressful context, I still remember Dick balancing a piece of chalk on his lip as I was trying to expound credibly on my proposed project. It was, I suppose, his way of lightening up. Much later, the last time I visited Dick and his wife Mary Jane in Cambridge, I heard a bit from them about a recent partial reconciliation with Ed Wilson. I was glad for both, and ever so lucky that Ed Wilson sent me to Dick Lewontin in the first place.

Just Another Human

Alan Goodman

In the spring of 2001, I was walking down Brattle Street near Harvard Square and encountered Dick and his wife Mary Jane, walking hand in hand. Dick recognized me immediately. I remember him calling out “Hi Alan!” He introduced me to his wife, and asked me what I was doing in Cambridge. I had no idea how he knew who I was.

Few years before, he and Dick Levins had written the foreword to my edited work, Building a New Biocultural Synthesis: Political Economic Perspectives in Biological Anthropology (with Tom Leatherman, 1998, Michigan). We corresponded scientifically but never personally; our discussion was mostly about the apportionment of human variation—this had been so ever since my graduate training in the early 1980s. We might have met only once in person, but I cannot remember the context. I was in Cambridge to work on Race: The Power of an Illusion (2003, California Newsreel), a documentary that ended up with both of us taking part independently. His amiability and memory took me by surprise.

A decade later, in 2012, he told me that he and Mary Jane were beginning to spend most of their days at their home in Marlboro, VT. Marlboro was just over an hour from my house, and I visited him whenever he could receive me. In addition to basking in his humanity and friendship, I had an ulterior motive: I wanted to start a biographical project on him. I was aware of his advancing age, and perhaps his declining memory. I asked if he was willing to write an autobiography or if someone was documenting his life. “Why me?” That’s all he said. But he didn’t exactly say no.

Thus, I began documenting his days in Rochester, Chicago, Cambridge, the early days of Science for the People, and lots more. He loved to talk about his mentors, collaborators, and students. In the process, I ended up learning so much more about other people than about Dick himself! And even more interesting was that he often reversed our roles and became the interviewer instead. He was very curious and inquisitive about my work, my laboratory, my teaching, and my life as a scientist from a different generation.

Then, Mary Jane’s health began to decline, first with a knee replacement in 2014, and he soon made the decision to permanently move back to Cambridge. From there, I was never able to complete my project and I lost my opportunity to tell the story of this loving, brilliant, yet humble human being who lived and breathed for others.

Dick died three days after Mary Jane. All his life, he always had others in his thoughts. So, he will always be in ours.