Review

Contingent and Structural Roots of Patriarchy

By Jensine Raihan

Volume 26, no. 1, Gender: Beyond Binaries

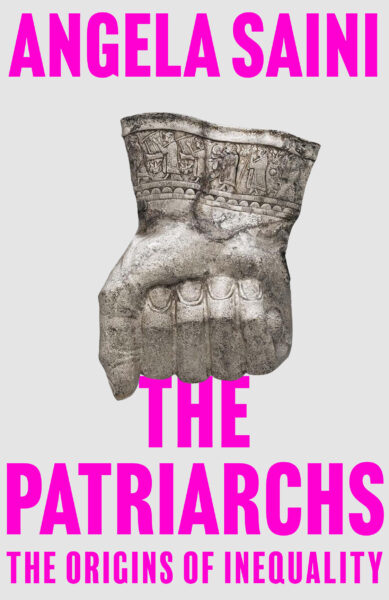

The origins of patriarchy have generally been thought to have commenced when violent nomadic men vanquished more “peaceful” societies.1 Angela Saini in The Patriarchs complicates this proposition that patriarchy was established by the sheer, brute force of violent men. Her book contends with this and a number of other commonly held beliefs about the nature of patriarchy that are broadly acknowledged both among male chauvinists as well as those invested in the destruction of patriarchy. She cites, for example, Christine Delphy and Michelle Rosaldo, both of whom point out that the widely accepted belief that patriarchy originated from the superior strength of vagabond men that destroyed supposed non-patriarchal societies is in fact a conjecture that uses modern culturally held beliefs about gender to explain their own genesis.2 In fact, Saini challenges pervading progressive thought that relies on culturally normative notions of gender in its reasoning of the foundations of patriarchy.

The origins of patriarchy have generally been thought to have commenced when violent nomadic men vanquished more “peaceful” societies.1 Angela Saini in The Patriarchs complicates this proposition that patriarchy was established by the sheer, brute force of violent men. Her book contends with this and a number of other commonly held beliefs about the nature of patriarchy that are broadly acknowledged both among male chauvinists as well as those invested in the destruction of patriarchy. She cites, for example, Christine Delphy and Michelle Rosaldo, both of whom point out that the widely accepted belief that patriarchy originated from the superior strength of vagabond men that destroyed supposed non-patriarchal societies is in fact a conjecture that uses modern culturally held beliefs about gender to explain their own genesis.2 In fact, Saini challenges pervading progressive thought that relies on culturally normative notions of gender in its reasoning of the foundations of patriarchy.

The Patriarchs is an ambitious project that seeks to understand how the widespread, yet heterogeneous, existence of patriarchy came to be. Saini inquires, if the experience of patriarchy is so universal, why does it take such diverse forms around the world? She answers this question through historical and anthropological findings that propel readers from one question to another across the globe stretching as far back as paleolithic times. Saini must unravel layers of myths and theories in order to arrive at a more stable hypothesis; in the end, she delivers a compelling investigation of what she shows are, in fact, the origins of patriarchies. Saini rejects the notion that there was a single moment in history in which women were decisively defeated and instead shows that domination by patriarchy requires daily reconstitution as it faces quotidian resistance. She joins other scholars like Massimilliano Tomba and Harry Harootunian, who argue that systems of oppression like patriarchy (for Saini) and capitalism (for the other two) do not spread in homogenous ways, but rather are responsive to local conditions, especially to the objective of the state, the condition of social struggle, and the general political terrain.3 Saini argues that women’s oppression and what we know as patriarchy really began to emerge in the written record once states and empires were forming. The state needed to ensure its survival through both defense and population growth.

A particular conceptualization of gender was used as a vehicle to serve the maintenance of the state. Saini believes that the state enforced gender roles in order to maintain itself through convincing women that their duty was to reproduce the state’s population and the duty of men was to defend it by serving in the military force. Since individuals’ gender expressions are in fact, diverse, the state needed to develop and compel particular performances of gender in order to maintain itself. To do this, the state developed a particular discursive narrative that crushed the legitimate existence of other forms of gender expression that threatened the existence of the state. She uses the distinctive gendered expectations in ancient Athens and Sparta that were formed due to the differing objectives of each state to showcase this theory. Whereas Sparta was focused on defense and as such had a particular kind of gendered expectation of women, namely to instill in their children and especially their sons the duty to defend the state, women in Athens, a city-state, were encouraged to adopt a subservient role of dependence to their husbands and reproduce children. Importantly, since many Athenian women were kidnapped from other communities, instilling women’s obedience to men was an important political move to curb rebellion. Using this example, Saini argues that the state has a formative role in normalizing particular ways of being, like how women and men perform gender and the kinds of social responsibilities they are obliged to. Although the structural influence of the state in reproducing social norms is undeniable, Saini’s argument on the decisive role of the state in cementing gender binaries overlooks the class-based nature of women’s oppression.

Her definition of patriarchy rejects a uniform sexual division of labor and instead emphasizes political, legal restrictions and typecast of particular genders (e.g., men as violent and women as nurturing) as features of patriarchy. As such, Saini largely ignores the central role women’s oppression plays in the capitalist mode of production and its reliance on a sexual division of labor to reproduce workers, and by extension to reproduce itself. Maria Mies in Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale, for example, argues that it was men’s monopoly over arms that cleared the way for a patriarchal organization of society; such a domination was motivated because those who had a monopoly over arms did not have their own means of subsistence and reproduction and so were compelled to subjugate others to fulfill this need.4 Mies’ theory does not point to a particular moment per se, though this theory is complementary to Saini’s own use of evidence of paleolithic warriors who migrated from the Eurasian steppes toward western Europe, and much later to South Asia in search of land and women because they were the younger descendants of their parents and so had no inheritance to their name. The records indicate that the migrants were overwhelmingly men and so this oddity compelled these men to reproduce with local women. It is also noted that these men came from a male-centered society that celebrated violence.5 In sum, although Saini’s approach of rejecting essentialized notions of men and women such as men being violent and women being nurturing is commendable and is effective in its argument that patriarchy is not innate, it is weak in its indictment of patriarchy and its particular European ontology, whose logic continues to maintain a monopoly of violence which serves the continuous subjugation of women’s reproductive capacities, diverse gender expressions, the environment, and postcolonial subjects through war, imperialism, and expropriation.6 As a result, one may be left to conclude that patriarchy is congruent for the formulation and defense of the state rather than a particular kind of ontology that uses a monopoly of violence to organize society (and therefore should be abolished).

The oppression of women and patriarchy generally is so widespread and dispersed that it lends credence to the chauvinistic notion of patriarchy as simply a consequence of greater male bodily strength. So goes the myth that there were once egalitarian, perhaps even matriarchal societies, that were vanquished due to the violent domination by men.7 Saini argues that such a historical narrative does not have sturdy evidence. Although new DNA analysis of paleolithic people points to a male dominated warrior society that migrated westward, and then much later to South Asia, from the Eurasian steppes and reproduced with local people, Saini believes that patriarchal norms cannot have been developed immediately through militaristic compulsion but must have taken thousands of years to take hold.8 She points to burial patterns of German graves in the middle of the third millennium BCE where there were no differences between women and men to suggest a lower social status among genders. This narrative of eastern men invading Europe and endangering local (white) women is still in vogue today and used to pass xenophobic legislation to “protect borders.” As such, she problematizes this narrative to suggest that patriarchal norms must have developed due to contingent local conditions and taken substantial time.

Biological strength and issues of inheritance are also commonly invoked to reason about the root causes of the development of patriarchy. These too she disputes by pointing to female dominated societies among bonobos who are slightly smaller than their male counterparts. Saini argues that it is not strength that is unequivocally valued among social species. Female bonobos, for example, create intimate social bonds with other females, even those they are not related to, which creates power relations that displace the possibility for individual males to dominate groups. The emergence of private property and the need for fathers to ensure that their resources get passed to their rightful heirs is also invoked as a reason for the advent of patriarchy.9 But as Saini shows, matrilineal societies endure even in societies with private property. She discusses the Nairs, “a powerful caste-based community” that dominated the Kerala region in India, where women to this day enjoy relatively higher privileges compared to the rest of the country. Nair communities were organized around a common female elder and women belonged to their natal home even after they had children. They enjoyed multiple partners and brothers raised their sisters’ children. In the nineteenth century, however, British colonizers believed such social organization was uncivilized and enacted legal reforms that elevated the status of the eldest men in these families. Instead of family disputes being handled in a shared manner, more power was legally given to the eldest men in the family. Eventually more Western models of family organization such as monogamy and smaller families became hegemonic and traditional organizations of matrilineality were seen through a colonial lens among locals as backward and embarrassing. However, Saini draws attention to the Khasi community in Meghalaya, India, which to this day has managed to maintain its matrilineal customs.

Saini contests the structuralist position of the progression of human civilization. According to the structuralist view, i.e. Morgan’s Ancient Society and Engels, primitive societies were matrilineal because it was the only way to track descendants with reliability.10 Once societies “advanced” with the emergence of private property, monogamy was enforced to ensure that inheritance gets passed down along patrilineal lines. Engels believed that with the destruction of private property, women’s emancipation is possible. Morgan and Engels both used contemporary indigenous people as a way to understand the past; i.e., instead of seeing Native people as their contemporaries, they saw them as living relics of the past. However, as Saini argues, this was contradictory as the very same Indigenous society that Morgan cites in his book, The Haudenosaunee Confederacy (otherwise known as the Iroquois), inspired the founders of the United States when they developed a representative republic from the first thirteen colonies.

The Haudenosaunee Confederacy were matrilineal and women wielded significant power including veto powers of wars. They enjoyed a level of economic agency and social freedom since they controlled the food production and were freely able to divorce. Saini argues that thinkers like Morgan and Engels had to go through mental gymnastics in order to reconfigure their contemporaries and pigeonhole them into “living skeletons.” She points out that they were only able to do so because implicit in their view was that Europe and Europeans were more advanced and Native Americans were savages because they were different despite their practice of advanced treatment of women and conceptualization of gender. In fact, Saini writes how the white suffragettes used Indigenous matrilineal organization as grounds for their own right for enfranchisement. Saini explains further that these suffragettes, however, did not return the favor when it came to the defense of Indigenous communities. Saini argues that the structuralist view gives a level of undue credence to the legitimacy of patriarchy even though its development was not inevitable but rather contingent. What Saini misses in her well-formulated critique, nevertheless, is that Morgan’s and Engels’ treatments of Indigenous people as relics of the past were themselves manifestations of their patriarchal ontology. Indigenous people were characterized as primitive, and therefore relics of the past, as a way to emphasize the supposed superior, advanced nature of European society and to legitimize the justification of the domination, subjugation and eventual quasi-eradication of American Indigenous communities and cultures. Indigenous people were relegated as part of nature and since civilization and man dominate nature (women similarly are designated as part of nature), they needed to be conquered. Since Saini’s treatment of patriarchy is not integrative as a theory of domination, this patriarchal manifestation could not be accounted for.

Saini shows that the direct and indirect influence of colonialism was a major player in the displacement of matrilineal societies—whether it was through legal reforms that advanced the political power of men in Kerala, Christian missionaries, or through European trading practices that displaced crafts trading dominated by American Indigenous women in favor of men. In some cases, men learned about alternative, patriarchal societies and advocated to organize society in tandem with those traditions. Saini effectively problematizes the notion that matrilineality is unusual and primitive, and encourages readers to consider the hegemonic discursive practice such a notion advances.

On the other side of the coin, Saini points to the significant shifts that state postcapitalist projects were able to achieve in the twentieth century that overtook capitalist countries. In these countries, the state provided daycare, cheap public laundries, canteens, and encouraged women to pursue careers in science, engineering, and mathematics. Women were encouraged to work, which allowed for economic independence. There were no expectations for women to cook dinner which allowed them a degree of liberty to pursue their careers. This occurred while in the United States women were encouraged to give up their jobs and become the ideal housewife. To demonstrate the marked advances that state postcapitalist projects were able to achieve, Saini compares Austria and Hungary. The countries share a border and have similar cultures, but Hungary adopted a number of socialist reforms that changed the condition of women, namely in regard to reaching gender parity among university students. Similarly, Saini highlights that in 2016 there was still a 23 percent gender wage gap in western Germany whereas in eastern Germany, it was only 6 percent.11 She argues that it was not market forces, economic development or an autonomous feminist movement that was able to achieve such drastic results in gender equality, but rather a redirection in the state’s objective. Saini is sure to mention that these projects did not mean that gendered division of labor was eliminated in the home. She is also keen to point out that top positions within the party in the USSR were dominated by men. Still, the transformation that these countries were able to achieve is significant. After the fall of the USSR and the surrounding postcapitalist projects, women saw a decline in their conditions. The argument and evidence that Saini illuminates here is considerable and an important contribution to the debate of the state. She writes,

That brief period of time was like hitting a reset button, beginning society again with new rules. Socialism proved that how the state was organized could have a profound impact on how people thought about themselves and each other, and it instituted that change perhaps more rapidly than any other regime has in history.12 Where it failed on gender equality was to forget that humans are cultural creatures, not automatons.” (173)

Throughout the chapter, Saini discusses how the USSR fell short in dismantling patriarchy, including sustaining gendered tropes that encouraged women to serve their social responsibility as mothers and caregivers, employing few female leaders among the party’s leadership, and paying female doctors lower wages than surgeons who were predominantly male. She believes the need for the reproduction of the state’s population and deeply held cultural beliefs about gender inhibited total dismantling of the patriarchy. However, Saini’s demonstration of the formative role the state can play in reshaping social relations is an important assertion for those invested in the project of liberation. Recent left movements have adopted anarchist trends that give up a strategy for winning state power, which is an extraordinary concession that renders liberation untenable.13 Saini highlights the compulsion to work required by many of the postcapitalist projects and a forced notion of gender promoted by these states, yet she is still able to point out the developmental role the state possesses in positive transformation of gender roles. To be sure, gendered division of labor in the home still remained in many of the states that lauded advanced gender relations suggesting that a top-down approach to shifting gender relations, though productive, is not sufficient.

Saini is able to further nuance the role of the state. She discusses the “gift” of women’s suffrage given by Mohammad Reza Shah, or more commonly known as simply “the Shah.” She argues that since women’s suffrage was granted paternalistically by decree to serve a particular political image rather than a democratic objective, it was precarious and was soon taken away due to the political terrain of Iran. That is, the franchise of women was not won through political struggle or a transformation of the state, which lent it to be precarious. Although Saini does not prescribe any formulation of “what is to be done,” her book still illuminates that a level of social struggle, as was developed in the victory of the October Revolution that led to the Soviet state, in tandem with a state whose objective is emancipation, is necessary for the destruction of patriarchy. Namely, Saini argues that the pursuit of democratic participation in political and economic power is essential for women’s emancipation along with a push in transforming cultural attitudes. She pays attention to the success of the state postcapitalist projects that were able to overtake capitalist nations in some aspects of gender relations.

Saini is able to poke a deflationary hole in the myth of the innate quality of patriarchy in a way that opens the door and inspires one to think about the horizon of freedom possible once we let go of our beliefs of what human nature is, which Saini illustrates is curated by the state. The Patriarchs delivers a complicated yet legible and elegantly written origin story of patriarchy that dispels commonly held beliefs about the nature of patriarchy. Saini joins an important tradition of scholars who highlight the contingent nature of oppression—a critical challenge to the fallacious argument, advanced by power, that the conditions of oppression whether it is male domination or greed is “just human nature.”

Without a doubt, The Patriarchs is an ambitious project that provides an important contribution to debates about gender, though it would be greatly advanced if it were to be in conversation with contemporary fascist and nationalist impulses in taking state power to reproduce gender relations. Why is there a resurgence of such movements in the current period? The Patriarchs additionally shies away from developing more profound theoretical understandings behind some of the attributes of patriarchy such as its affordance to men of particular rights to violence (shared of course by the state) and the function of reproductive labor and the reasons behind its privatization in society. Saini’s commitment to demonstrating the contingency of patriarchy lends the book to some pitfalls, including largely ignoring the profound economic reliance on women’s reproductive labor and the expropriation of working class women and trans people. When Saini insists that patriarchy takes many forms globally, she abdicates the longstanding feminist understanding of the continuous threat of violence experienced by all women but especially working class women and trans people.

The book relies on developing an accessible narrative from new scientific discoveries that focuses on the historical emergence of patriarchy rather than a deep theoretical interrogation of aspects of patriarchy as a whole, like that of violence and reproductive labor. It also relies on identifying anomalies to patriarchal customs as evidence for its argument that patriarchy was not inevitable. This is a reasonable and important move but falls short in developing a political economy account of the function of patriarchy, its use of violence, the role of reproductive labor and the reasons behind its resurgence globally. Nevertheless, The Patriarchs is an important contribution to debates about patriarchy and offers important lessons that challenges many of our assumptions about the inherent character of human beings.

The Patriarchs is a compelling book to read in our current time when we are seeing rapid rollbacks in access to reproductive and gender-affirming care and sex education.14 When Saini argues that gender is used as a vehicle for states to ensure its own reproduction, it reflects the infamous words of neo-Nazi David Lane who says, “We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children.”15 Florence Ashley and Blu Buchanan argue in their op-ed, “The Anti-Trans Panic is Rooted in White Supremacist Ideology”, that moves to restrict abortion access to ensure the reproduction of white children come from the same impulse that is blocking gender-affirming healthcare, eliminating black men from their communities through the criminalization of their lives, the sustenance of high maternal mortality rates among black women, stigmatizing reproduction by women of color through racist tropes like welfare queens, continuous sterilization of Black and Latine women, and continuous disenfranchisement of communities of color.16 That is, there is a current move to sustain majoritarian control by white people and eliminate communities of color from political participation and society generally.

Notes

- In her widely acclaimed book Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale in the International Division of Labor (1986), Maria Mies theorizes that it is the male monopoly over arms that provided the means for male domination over society, women, and nature. This pioneering theory argues that weapons, which are believed to be the first invention by men in particular, were really appropriative tools, not productive in and of itself, that allowed for the appropriation of productive goods like harvested food, women and other slaves. Mies argues that once agricultural production was formed, pastoral nomads used their monopoly over arms to pillage these societies and establish a new mode of production that “presupposes a means of coercion for the manipulation of animals and humans” and thereby establishing a class order that, among other hierarchical roles, subordinates women.

- Christine Delphy, Close to Home: A Materialist Analysis of Women’s Oppression, trans. and ed. Diana Leonard Hutchinson, 1984. (University of Massachusetts Press, 1984); Michelle Zimbalist Rosaldo, “The Use and Abuse of Anthropology: Reflections on Feminism and Cross-Cultural Understanding,” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 5, no. 3 (Spring 1980): 389–417. https://doi.org/10.1086/493727.

- Like Saini, Tomba and Harootunian contest a uniform progression of history. They argue that the international spread of capitalism is heterogeneous and this process of formal subsumption has within it many antagonisms. For Tomba, this does not mean that there are diverse capitalisms but rather that local economic forms get directed to the rationality of capitalism, but these local forms are still important in the local iteration and constitution of capitalism. Harootunian, along the same lines, argues that there is not one modernity that everyone experiences but places like the American south, and especially the conditions unveiled during the aftermaths of Hurricane Katrina, demonstrate the “noncontemporaneous contemporary” that exists in our contemporary world.

- Maria Mies, Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale: Women in the International Division of Labour (London and Atlantic Heights, NJ: Zed Books Ltd, 1986).

- David Reich, Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018).

- Along with Maria Mies, Cedric Robinson (1983) and Silvia Federici (2004) to name two among many have shown the particular ideology of destruction and violence to subjugate “others” (including Europe’s own women) coming out of Europe that served as a kind of genesis to the European strain of patriarchy, colonialism, capitalism, imperialism, etc.

- Ruth Mace, “How Did the Patriarchy Start–and Will Evolution Get Rid of It?” The Conversation, September 20, 2022, https://theconversation.com/how-did-the-patriarchy-start-and-will-evolution-get-rid-of-it-189648.

- Reich, “Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past”.

- Mace, “Patriarchy”.

- Lewis Henry Morgan. Ancient Society: Or Researches in the Lines of Human Progress from Savagery through Barbarism to Civilization, (New York: Henry Holt & Company, 1877); Friedrich Engels, The Origins of the Family, Private Property, and the State (1884).

- Michaela Fuchs, et al. “IAB Discussion Paper 201911: Why Do Women Earn More Than Men in Some Regions? Explaining Regional Differences in the Gender Pay Gap in Germany,” Institute for Employment Research, Nuremberg, Germany, 2019.

- Although Saini discusses the USSR and surrounding state projects as “state socialism,” this is contested and can be better understood as postcapitalist societies.

- “Mapping Attacks on LGBTQ Rights in U.S. State Legislatures,” American Civil Liberties Union, accessed August 25, 2023, https://www.aclu.org/legislative-attacks-on-lgbtq-rights.

- “Mapping Attacks on LGBTQ Rights in U.S. State Legislatures,” American Civil Liberties Union, accessed August 25, 2023, https://www.aclu.org/legislative-attacks-on-lgbtq-rights.

- “David Lane,” Southern Poverty Law Center, accessed June 12, 2023, https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/individual/david-lane.

- Florence Ashley and Blu Buchanan, “The Anti-Trans Panic Is Rooted in White Supremacist Ideology,” Truthout, May 19, 2023, https://truthout.org/articles/the-anti-trans-panic-is-rooted-in-white-supremacist-ideology/.