The Metabolism of Naval Power

Watermills in Long Nineteenth Century Ontario

By Johannes Chan

Volume 25, no. 3, Killing in the Name Of

Watermills in long nineteenth century Ontario were integral to the colonial project of Canada, converting swathes of forest into vehicles of British naval power. In doing so, watermills were not only technologies central to a large-scale project of deforestation but also radically transformed river ecosystems, bringing local salmon species—on which Indigenous nations like the Anishinaabe relied—to the point of extinction. This environmental violence enabled both land and water dispossession, directly resulting in present-day Anishinaabeg grievances and disputes with the colonial state.

The result of this dispossession was a rapid accumulation of wealth and power by a class of colonial insiders including land surveyors, colonial administrators, and merchant millers. Some became reputable scientists and others high-ranking government officials.1 Several not only profited from the environmental violence mills entailed, but also gained from the dispossession and enslavement of Black and Indigenous people along the Cobechenonk river, also called the Humber River.2 Capital accumulation in Toronto cannot be understood outside this context of watermill development and the attendant fish population collapses, deforestation, colonial militarization, and slavery that the milling economy depended upon. This history illuminates how past environmental exploitation around Toronto was a direct result of British imperialism’s global military and commercial ambitions, and helps contextualize ongoing Indigenous and anti-colonial struggles over energy infrastructure, water, land, and self-determination.

Colonial Deforestation and Fish Decline

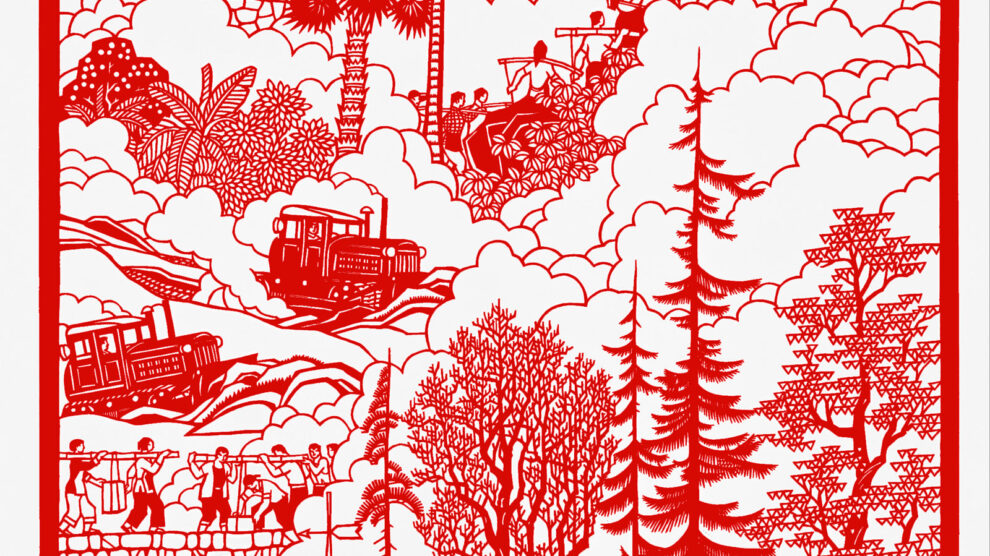

Between the 1787 Toronto Purchase from the Mississaugas and the year 1910 when Niagara Falls began delivering electricity to neighboring cities and towns, watermills proliferated along rivers throughout Ontario.3 Numbering almost seven hundred by 1851, they processed commodities like lumber, grain, minerals, and textiles. Colonial sawmills in particular precipitated two related and significant environmental transformations in Upper Canada; deforestation and the collapse of fish populations.4 Samuel Wilmot, a land surveyor for the Royal Navy and later a founding figure of Canadian fish hatcheries, straddled both these ecological changes in his career. The forests he surveyed were transformed by sawmills into lumber for Navy ships. Watermills constructed for capitalist production and British imperial ambitions facilitated the rapid denuding of forests and rivers, Indigenous dispossession, and increased colonial domination over nature.

Early nineteenth century land surveyors like Wilmot observed almost uninterrupted forest cover around the Missinihe (Credit River) watershed near Toronto. But by 1850, tree cover dropped to 67 percent and reached 9.5 percent by 1911.5 The Anishinaabeg ethnobotanist Jonathan Ferrier referred to this process of clear-cutting in Ontario as a “genocide by sawmills.”6 The rich forest ecosystems that once served as important foraging and hunting territory for the Anishinaabe and Haudenosaunee were replaced by large settler farms growing commodity monocrops for export.

Environmental transformations in Upper Canada mirrored what was also occurring back in the metropole. Engels in The Condition of the Working Class in England drew on experiences of family textile mills along Manchester waterways to detail the many miseries of working-class life. As these mills processed cotton from American slave plantations, Engels documented the concurrent environmental degradation they produced.7 During the nineteenth century, both metropole and colony witnessed the environmental toll capitalist development takes on river ecosystems and laboring bodies.

However, as Richard Lewontin pointed out, environmental change is a universal characteristic of all organisms that both produce and destroy conditions conducive to their existence.8 Watermills were also not invented by European colonial powers, with likely origins in Asian antiquity.9 What made colonial transformations of Ontario’s environment distinctive was the role capitalist development played in concert with British imperial and military interests. The British imperial state, like Thucydides, conceived of forests as a lumber source for military ships and justification for conquest.10 Deputy Surveyor Samuel Wilmot arrived at the Missinihe in 1806 to mark off the boundaries of the Mississauga’s Reserve and was instructed to “note Timber . . . Pine & Oak for the Royal Navy.”11 The sawmills that eventually processed this military timber would then drastically alter river ecosystems and fish populations.

Fisheries science in Canada developed in the interest of colonial systems of power and is best understood in that context.12 Wilmot became integral to this history after observing salmon numbers declining in the creek running through his farm in the 1850s. He later became a pisciculturist and received government funding for experimental research projects to restore fish populations in rivers he himself played a vital role in depleting.13

Jurisdiction of waterways around Toronto today falls under colonial state power, despite remaining unceded by the Mississaugas of the Credit who have an ongoing title claim to all waterways within their traditional territory.14 Colonialism in Upper Canada involved the conquest and repurposing of Indigenous land and resources for capitalist production and military vessels, resulting in the rapid decline of both fish and forest cover. Wilmot is memorialized as a figure who restored fish populations in Ontario, but colonial resource management projects like his were established to regulate forest and river ecosystems that colonial watermills themselves disassembled. The cumulative impact of this environmental history continues to structure the ongoing oppression of Indigenous nations today.15

Environmental Violence is Colonial Violence

Cree Métis scholar Zoe Todd sees fish as more-than-human actors who bore witness to the environmental violence done to Indigenous waterways.16 Sawmills both destroyed fish populations and processed military lumber, making them sites where environmental and imperial violence converged. Sawmill dams blocked fish migration, waterwheels injured and killed fish, and large volumes of sawdust proved toxic to fish and humans alike. The colonial state knew about the consequences of watermills but continued to subsidize their construction, even establishing state sawmills to supply military shipyards. The military violence of the British empire relied materially upon the environmental violence committed upon Toronto rivers.

The Cobechenonk river was an important spawning ground in the eighteenth century, abundant in aquatic life. The Mississaugas of the Credit depended upon salmon returning to the Cobechenonk and Missinihe each year for their livelihoods.17 An important turning point occurred in 1791 when Governor John Graves Simcoe declared watermills a central pillar of colonial policy. He made state-provisioned materials available for mill construction and considered watermills both “universally necessary” and “a great inducement to the settlement of lands.”18 Salmon populations on the Cobechenonk and Missinihe dwindled in subsequent decades, reaching extinction by the 1850s.19

Administrators were not unaware of how watermills affected rivers. A colonial land surveyor noted in 1796 “a great quantity of salmon as well as other fish destroyed by the wheels of [a] sawmill.”20 Similarly, the colonial administrator Peter Russell recommended the use of wicker stops “to prevent the salmon from being . . . cut to pieces by the wheel,” and that “free passage shall be left for the salmon and other fish to ascend and descend the River.”21 Despite Russell’s professed concern for fish, it appears he made little progress towards realizing his recommendations, as the same issues were still being raised decades later.22 Instead of taking effective measures to protect fish, a month after Russell was appointed to oversee government mills, he established a military shipyard on the banks of the Cobechenonk in Toronto and directed the King’s Mill on the river to begin processing lumber for the new Royal Navy shipyard.23

Beyond obstructing migration, sawdust from these mills also proved toxic to fish, and anglers blamed sawmill refuse on dwindling salmon numbers.24. The Anishinaabe also noticed this decline and requested their fishery be protected.25 The effects were not limited to fish, however. The Mississauga leader, Peter Jones, noted an outbreak of cholera in 1832 among an Anishinaabeg community along the Cobechenonk, and medical scientists in subsequent decades began trying to connect sawdust pollution with cholera outbreaks in Upper Canada.26 Sawdust exposure is now recognized as a potential carcinogen and in the 1970s became the subject of organized labor grievances by Pacific Northwest forestry workers.27

The environmental violence that occurred under Russell’s supervision of mills and imperial shipyards was only one aspect of this period’s colonial violence. Russell himself was also a slave owner in Toronto.28

Slavery on the Cobechenonk

“Antipatros,” Marx noted, “a Greek poet of the time of Cicero, hailed the invention of the water-wheel for grinding corn, an invention that is the elementary form of all machinery, as the giver of freedom to female slaves, and the bringer back of the golden age.”29 Though watermills are often associated with declines in slavery, the construction of watermills along the Cobechenonk remained for some time coupled to the enslavement of Black and Indigenous people.30

Governor Simcoe, though a self-professed abolitionist, brought Russell into his administration in 1796, a year before Simcoe left for the Caribbean to help suppress the Haitian Revolution.31 Slave owners in the administration like Russell seriously obstructed anti-slavery legislation from passing. Russell enslaved three children named Amy, Jupiter, and Milly, along with their mother Peggy Pompadour. The Pompadours engaged in tactics of resistance, including escape attempts and acts of refusal, but faced serious repercussions including prison sentences. Amy Pompadour would be one of the last legally enslaved persons in Upper Canada.32 Her life after release was characterized largely by poverty. She died in 1865 as an inmate of a Victorian workhouse known as the Toronto House of Industry, suffering conditions proximate to those of her slave years.33 Amy’s owners were not alone as enslavers among the Cobechenonk milling elite.

John Scarlett, whose family became wealthy millers and lumber merchants, arrived at the Cobechenonk with a slave named James who Scarlett had purchased in Antigua for £144.34 Scarlett’s son Samuel is credited as the only merchant miller in the Cobechenonk watershed to attempt reforestation efforts through a tree nursery in 1857. However, this would prove insufficient to stop the watershed’s deforestation. Large-scale lumbering operations overseen by the Scarlett family were responsible for denuding the Humber valley by 1860.35

Perhaps the most notorious slave owner on the Cobechenonk was James (Jacques) Bâby. The Bâby family enslaved at least eighteen Black and Indigenous people including an Indigenous woman named Marie Louise, and her children Rosalie, Louis, Catherine, Augustin, and Basile.36 Bâby arrived on the Cobechenonk in 1815 as Inspector General and had acquired fifteen hundred acres on the river’s east bank by the 1820s.37 His estate was situated atop the Haudenosaunee village Teiaiagon—an area now known as Bâby Point.38 The Bâby family operated mills but were better known as one of the most powerful landlord families in Upper Canada, amassing many thousands of acres across the colony.

Slavery was an important facet of Toronto’s violent colonial history. The Cobechenonk’s slavers included colonial administrators, lumber merchant millers, and powerful landlords, who profited not only from the burgeoning watermill economy of Upper Canada, but also from the enslavement of Black and Indigenous persons. Affluent settler families accumulated large amounts of wealth during this period through various forms of dispossession. The Fishers, one such family, were influential merchant-millers who were close friends of the Bâby family and made their wealth along the Cobechenonk by servicing empire for generations.39

Colonial Accumulation by Indigenous Dispossession

Thomas Fisher arrived at the Cobechenonk in 1821 to lease the King’s Mill and its timber reserve. In 1834, he purchased the mill-site from the government and sold it in 1835 for a profit.40 David Harvey called this process of privatization “accumulation by dispossession,” where wealth is concentrated through the dispossession of the public.41 However, preceding this dispossession of the public, an earlier layer of Indigenous dispossession occurred, something the Yellowhead Institute calls the “cumulative impact” of “land alienation and ecological destruction.”42 Generations of the Fisher family would continue this process of accumulation by the dispossession of colonized peoples.

Thomas Fisher supplied the Royal Navy with lumber clear-cut from Anishinaabeg land and his son helped put down the Métis Northwest Resistance with the Boulton’s Scouts militia. Fisher’s grandsons were engineers who designed military communications equipment used by Israel in the Six-Day War, U.S. military intervention in Vietnam, the militarization of South Asia, as well as in later fossil fuel extraction projects.43 This accumulation of wealth enabled the Fishers to amass a large collection of rare books now found in the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library at the University of Toronto. The Fisher Library houses a copy of Shakespeare’s First Folio and various prized collections including a vast archive of radical political material known as the Robert S. Kenny Collection.44 But its principal eponym remains a man whose family loyally served the cause of the empire for generations. The Cobechenonk’s milling history has become inscribed into the name of Canada’s largest publicly accessible repository of rare books. This testifies to how colonial institutions like the University of Toronto have directly benefited from this generational history of riverine dispossession.

Watermills, though not uniquely colonial technologies, became key infrastructures underlying naval expansion, funded by the colonial state in Upper Canada to establish an increased settler presence. These mills metabolized forests and swift river currents into vessels of naval military power with global reach. The nineteenth century milling economy of Toronto and the capital accumulation it facilitated, depended upon both colonial militarism and processes of Black and Indigenous dispossession—including large-scale deforestation, the collapse of local fish populations, and enslaved labor. This history of dispossession has persistent consequences that continue to structure the ongoing colonial project of Canada today. Yet, Indigenous resistance against colonialism also continues, from Anishinaabeg Water Walkers organizing against water pollution in the Great Lakes region to Wet’suwet’en struggles against pipelines crossing the Wedzin Kwa river.45 Water defense remains among the most active sites of struggle for Indigenous nations today.

—

Johannes Chan is a PhD student in Science and Technology Studies at York University researching the environmental history of watermills in long nineteenth century Ontario and their relation to British colonialism and empire.

Notes

- A.B. McCullough, “WILMOT, SAMUEL,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography (University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003).

- Adrienne Shadd, Afua Cooper, and Karolyn Smardz Frost, The Underground Railroad: Next Stop, Toronto (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2022).

- R.N. Beattie, “The Impact of Hydro on Ontario,” in Profiles of a Province: Studies in the History of Ontario. (Toronto: Ontario Historical Society, 1967).

- Arthur Doughty, “Notes on History of Flour Milling in Canada,” November 24, 1936, John Ross Robertson Manuscript Collection, Folder for Alfred H. Bailey, Marilyn and Charles Baillie Special Collections Centre, Toronto Reference Library.

- V.B. Blake, Credit Valley Conservation Report 1956 (Toronto: Dept. of Planning and Development, 1956).

- Jonathan Ferrier, “Natives in ‘Animosh’: The Land of the ‘Dog’, ‘Eramosa’ Township,” http://mncfn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Ferrier-PPT-Credit-meeting-final-low-res.pdf.

- Friedrich Engels, The Condition of the Working Class in England (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1987); Eric J. Hobsbawm, The Age of Revolution 1789-1848, (New York: Vintage Books, 1996).

- Richard Lewontin, Biology as Ideology: The Doctrine of DNA (Concord, ON: Anansi, 1991).

- Joseph Needham, Science and Civilization in China, Volume. 4, Part. 2: Mechanical Engineering (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1965).

- Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009).

- Samuel Wilmot, “Diary of Samuel Wilmot,” 1806, Microfilm, MS 7438, Archives of Ontario.

- Jennifer J. Silver et al., “Fish, People, and Systems of Power: Understanding and Disrupting Feedback between Colonialism and Fisheries Science,” The American Naturalist 200, no. 1 (2022): 168–80.

- McCullough, “WILMOT, SAMUEL.”

- Joan Holmes & Associates, “Aboriginal Title Claim to Waters within the Traditional Lands of the Mississaugas of the New Credit,” 2015, https://mncfn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/MNC-Aboriginal-Title-Report.pdf.

- Yellowhead Institute, “Land Back” (2019): 30, http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep32601.

- Zoe Todd, “Refracting Colonialism in Canada: Fish Tales, Text, and Insistent Public Grief,” in Coloniality, Ontology, and the Question of the Posthuman, 1st ed. (Routledge, 2018), 131–46.

- Kathleen Lizars, The Valley of the Humber 1615-1913 (Toronto: William Briggs, 1913).

- Doughty, “Notes on History of Flour Milling in Canada.”

- Donald Smith, Sacred Feathers: The Reverend Peter Jones (Kahkewaquonaby) and the Mississauga Indians, Second Edition, (University of Toronto Press, 2000).

- Augustus Jones, “Letter to Acting Surveyor-General D.W. Smith on July 7, 1796,” July 7, 1796, Microfilm, MS 7433, Archives of Ontario.

- Peter Russell, The Correspondence of the Honourable Peter Russell (Toronto: The Society, 1932), 58.

- Lizars, The Valley of the Humber.

- Sidney T. Fisher, The Merchant-Millers of the Humber Valley: A Study of the Early Economy of Canada, (Toronto: NC Press, 1985).

- Lizars, The Valley of the Humber; Thomas William Magrath, Authentic Letters from Upper Canada, (Dublin: Wm. Curry, 1833), 292.

- Peter Jones, Life and Journals of Kah-Ke-Wa-Quo-Na-By (Rev. Peter Jones), Wesleyan Missionary, CIHM/ICMH Digital Series; No. 35351 (Toronto: A. Green, 1860), 199.

- Jones, Life and Journals, 352; Randy Boswell, “Cholera, the ‘Sawdust Menace,’ and the River Doctor: How Fear of an Epidemic Triggered Canada’s First ‘Pollution’ Controversy,” Histoire Sociale 49, no. 100 (2016): 503–42.

- Erik Loomis, Empire of Timber: Labor Unions and the Pacific Northwest Forests, Studies in Environment and History (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2016).

- Shadd et al., The Underground Railroad.

- Marx, Capital: Volume 1.

- Terry Reynolds, Stronger Than a Hundred Men: A History of the Vertical Water Wheel, (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003).

- Edith Firth, “RUSSELL, PETER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography (University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003). Donald B. Smith, “Simcoe in Haiti,” Horizon Canada, no. 112 (1987).

- Robert E. Denison, A history of the Denison family in Canada, 1792 to 1910, (1910), 12.

- Shadd et al., The Underground Railroad.

- Lewis Butler, “Antigua Slave Deed for John Scarlett,” 1809, http://archive.freerangephotography.co.uk/D1118/index.html.

- Fisher, The Merchant-Millers.

- Camal Pirbhai and Camille Turner, House of Bâby (Lenticular Print, 2021), https://www.camalandcamille.com/house-of-baby. Marcel Trudel, Canada’s Forgotten Slaves: Two Hundred Years of Bondage, (Montreal: Véhicule Press, 2013).

- John Clarke, “BABY, JAMES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, 2003.

- Jesse Thistle, “‘We Are Children of the River’: Toronto’s Lost Métis History,” Revue YOUR Review (York Online Undergraduate Research), 3 (October 2017): 11–28.

- Fisher, The Merchant-Millers.

- Fisher, The Merchant-Millers.

- David Harvey, The New Imperialism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003).

- Yellowhead Institute, “Land Back,” 30.

- Fisher, The Merchant-Millers.

- Anne Dondertman and Sean Purdy, “The Robert S. Kenny Collection on Communism and Radicalism at the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto,” Labor History 39, no. 4 (1998): 397–405.

- Kyle Whyte and Chris Cuomo, “Ethics of Caring in Environmental Ethics: Indigenous and Feminist Philosophies,” in The Oxford Handbook of Environmental Ethics (Oxford: University of Oxford Press, 2015): 234-247. Brandi Morin, “DEFENDING THE SACRED,” Cultural Survival Quarterly, 46, no. 2 (2022): 24–25.