Organize the Lab: Theory and Practice

Chapter 5

STEM Organizing in Waves: A Macro and Micro View

By Trent McDonald and Jewel Tomasula

For Colin Kluender (1995–2021),

Washington University Biophysics graduate worker and union organizer.

* * *

A specter is haunting labs—the specter of labor unions.

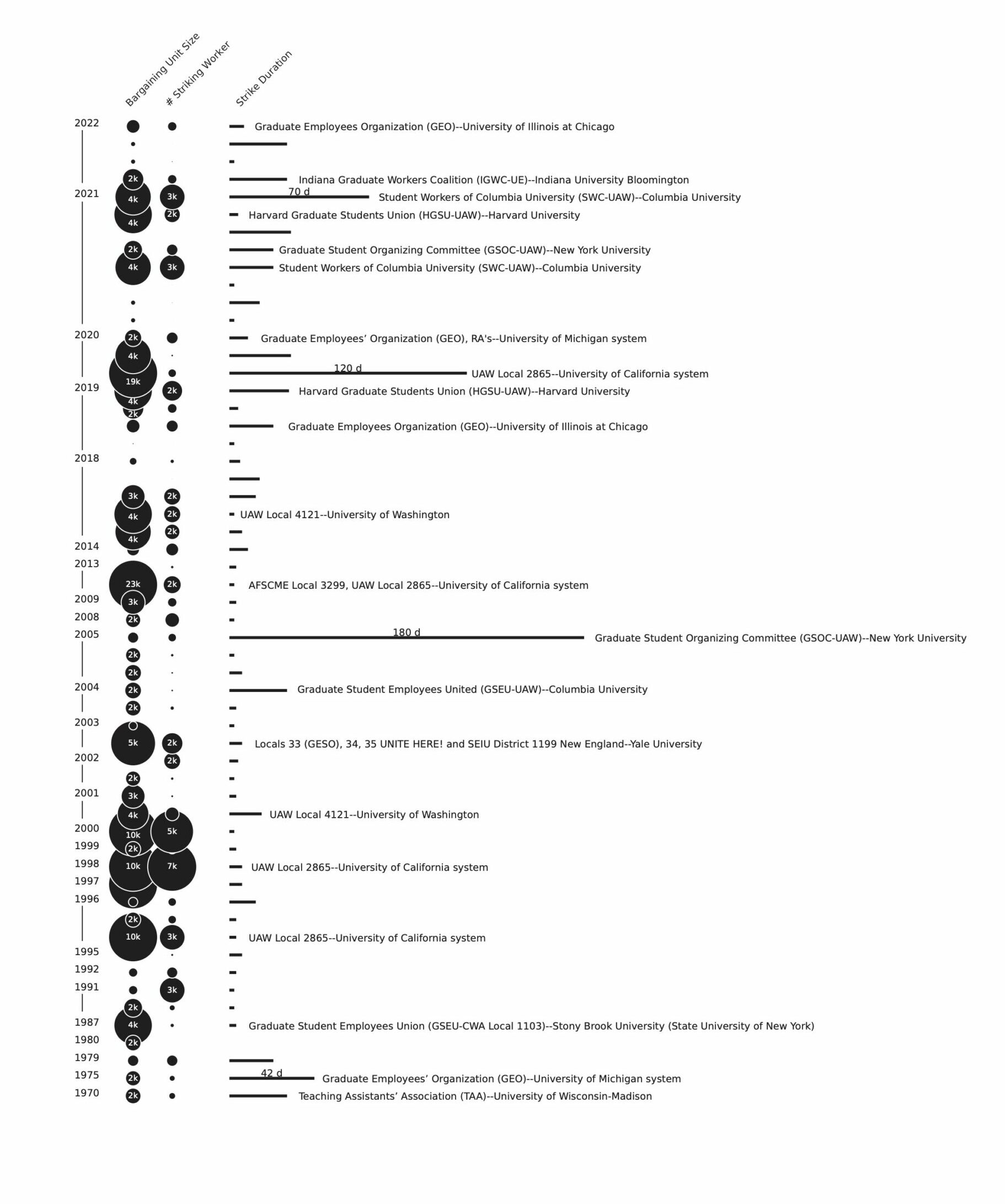

On the evening of December 8, 2021, history was made when the University of California system recognized that the majority-STEM UC Student Researchers United-United Auto Workers (SRU-UAW) had won the healthy support of 10,441 out of a total of 16,741 workers across ten campuses and the Lawrence Berkeley National Lab.1 SRU had previously filed their union authorization cards for union certification and recognition with the state Public Employee Relations Board in May. Yet the university administration refused full union recognition. They attempted to exclude some student workers from union coverage based on which funding source paid the workers.2

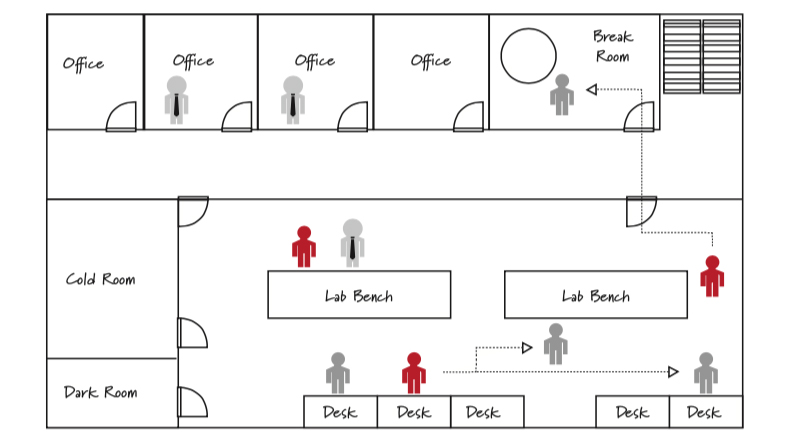

This response prompted union marches across the state, pressure on the university administration from California legislators, and an extraordinary strike vote. Out of 10,890 votes, with a 97.54 percent margin, 10,622 grad workers voted to authorize a union recognition strike; assuming the bargaining unit remained largely stable, this was also a high 65 percent voter turnout (see figure 1). SRU gained nearly two hundred more strike voters over the initial number of union supporters. Their commitment to demonstrating public declarations of union support through communications and marches are textbook examples of good worker organizing, as they show management how thoroughly the union has organized the workforce. The SRU workers drove the largest successful union recognition campaign by any union in the United States last year (one of the largest in decades), and the biggest single union recognition campaign ever for US campus workers (and, considering the size of US higher education, likely the largest in the world).3

Also having won a union recognition campaign was the Union of Pitt Faculty; 3,355 faculty members in affiliation with the United Steelworkers (USW) won 69 percent of the vote at one of the most federally grant-funded campuses, the University of Pittsburgh, after a half-decade-long campaign.4 And of last year’s three largest campus strikes—six thousand workers total across Harvard, Columbia, and New York University—STEM grad workers were loyal picket line marchers.5

In the first half of 2022, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a longstanding elite institution for STEM research, also had to contend with the MIT Graduate Student Union-United Electrical Workers (MIT GSU-UE). This large STEM workforce voted to unionize 1,785 to 912, a high turnout of 71 percent of the grad workers from the 3,823 eligible workers. This was the second largest successful union recognition campaign of the year so far, behind only the extraordinary Amazon Labor Union victory in New York for 8,235 workers.6 Two months later, UAW Local 4121 won a union certification vote 606 to 104, a 48 percent voter turnout, for 1,458 Research Scientists and Engineers at the University of Washington, capping off an extraordinary period for STEM worker organizing.7 To take a longer view, since the turn of the millennium, unions have organized over 40,000 STEM workers (and counting).

The STEM workers waging these union recognition and contract campaigns are among the greatest organizing successes in a country where as of last year, only 10.3 percent of workers are union members and 11.6 percent have union representation.8 Over 20 percent of the UAW’s storied membership have become campus workers, and the radical UE is also on a student worker organizing hot streak, indicative of the growing shift in the US economy away from industrial manufacturing.9

And, like the alleged conservatism of blue-collar workers, academic STEM workers get an undeserved bad rap through some of the counter-organizers among their ranks.10 These anti-union student workers loudly agitate against being “forced” into a union with underpaid humanities and social science workers.11 Anti-union STEM workers can, as always, point to data on the other side of their graduate and postdoctoral careers. In contrast to non-STEM workers who have an average yearly salary of $40,120, STEM workers receive a higher average pay of $95,420, and only 9.6 percent of them are union members.12 The bridge between STEM and humanities and social sciences work has always been challenging to build.

University administrators at places like Washington University and Penn State University rely on their union busting lawyers to shamefully double down on these workforce divisions across lines of discipline, nationality, race, gender, etc.13

The intrepid STEM organizer surely reads these lines and sighs at their familiarity. With all of the odds stacked against STEM workers organizing—-as with many other workers’ organizing—why are the more than 40,000 newly unionized workers bucking the trend?14 Are they merely a skewed data set?

Many graduate and postdoctoral worker unions have won impressive victories across several institutions.15 STEM workers with specialized skills, like all workers, take collective action when they see how their participation in union activity is necessary to secure their livelihoods and ensure their material well-being, among other deeply and widely felt issues. The technology industry, seen by many in academic STEM as insulated from the precarity of work in other non-technical fields, has recently been roiled by layoffs at Netflix, Alphabet, and the online trading platform Robinhood; and even biotech employment is unstable.16

If the predictions of a possible recession are realized in the coming year, government spending on science research could plummet, as it did following the 2001 dotcom bubble and the 2008 Great Recession.17 Even if it were true that a STEM degree provides a fortress against future economic precarity (it does not), there are many immediate concerns that STEM student workers could address through unionization. Wages and benefits like health insurance and retirement contributions are important, of course, but tearing down the exploitations of long lab hours; horrific sexual harassment; widespread bullying; racist, sexist, xenophobic hierarchies at work; and other indignities also matter enormously.18 The worsening mental healthcare crisis for student workers specifically remains a strong motivating force for worker organization.19 Organizers must know these issues and identify how people are already organized socially and productively. STEM workers will deploy those associations and affiliations to address insults, injuries, and injustices when asked.

Solidarity is always a motivating force, too. It is pertinent to always ask the question, “What would you change about the university or the city if you could?” Many STEM workers offer responses, “we object to humanities grad students’ salary/status/treatment being lower than ours.” An injury to one is indeed an injury to all. Replicating that question thousands of times across the nation, the solidarity of thousands of new, dedicated STEM union worker organizers becomes apparent.

The recent upsurge in STEM unionization, while extraordinary, is not unprecedented. A closer look into the history of the clash within the scientific management of scientific labor reveals an understudied past.20 The period from 1933 to 1945 saw a surge in private sector unionization, which was not only confined to industrial factories.21 White-collar workers, too, took notice that the terrain of labor relations had fundamentally changed from low to high worker empowerment and they built solidarity and coordinating capacity with manufacturing workers.22

Among the most notable of the new white-collar organizations was the Federation of Architects, Engineers, Chemists, and Technicians (FAECT), established in August 1933 out of the failures of the architect and engineer professional organizations to provide stable employment and fair wages during the Great Depression.23 In a little over a year, their national membership grew from five hundred to 6,500.

Taking inspiration from the blue-collar production workers’ movement from below against authoritarian workplace management, these architects and STEM workers built a militant union unafraid to boycott, picket, and strike for economic and social issues, including steady jobs with fair pay in the public and private sectors and the desegregation of hotel accommodations during an annual convention.23 The union also established the FAECT School for further professional education and was instrumental in passing the Housing Act of 1937, which won $450 million ($6.76 billion today) for the federal subsidization of local public housing agencies, helping their members work for the public good. FAECT’s socialist and communist leadership declared their commitment to assisting their fellow production workers’ fight for dignity and ending global fascism through active participation in the left-liberal Popular Front. During the 1940s, the union even earned a seat at the table coordinating the conversion of some factories to anti-fascist wartime production, an extraordinary breakthrough against traditional management rights.24 Upon joining the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO; autonomous from 1935 to 1955) labor federation alongside the UAW, UE, and USW in 1937, they coordinated organizing with blue-collar manufacturing workers in auto, electrical, and steel.

Unfortunately, the Second Red Scare took over many facets of American society, including the mainstream of the labor movement.25 Nuclear physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer and engineer Julius Rosenberg were FAECT members, inspiring Congressional investigation into and public backlash against the union.26 Cut off from their previous associational power and support from other unions, FAECT turned to waging defensive battles for survival instead of offensive struggles for new members. FAECT found a safer harbor through affiliation with the left-led United Office and Professional Workers of America (UOPWA) in 1946, which also waned under the force of anti-communist attacks.

The CIO’s ascendant anti-communist right wing, led by the USW’s Philip Murray and the UAW’s Walter Reuther, purged the progressive wing from the federation in 1949–1950, including the FAECT, UOPWA, and UE, for alleged communist domination.27 These policies ended further organizational growth, and white-collar unionism was set back for decades, until the larger (i.e., not specifically STEM) public sector union upsurge of 1959 to 1979, when 400,000 union members became 4 million.28 STEM teachers and municipal and state-employed scientists and engineers were active in these fights, but the unions they produced largely did not share the socially transformative view of unionization shared by the blue-collar and white-collar radicals of the 1930s.

FAECT’s UOPWA eventually joined District 65 of the Distributive, Processing, and Office Workers of America, which was affiliated with the UAW in 1979.29 District 65, mostly now UAW Local 2110 (which represents many New York white-collar campus workers), also lives on in UAW Local 2865, which represents the more than 19,000 non-research assistant student workers of the University of California system and who were instrumental in last year’s student researcher campaign. Although FAECT’s lifespan was a short thirteen years, past labor struggles live on.

Closer to the present, there was another moment of STEM worker militancy that could have dramatically reshaped the terrain of American white-collar work. The Society of Professional Engineering Employees in Aerospace (SPEEA), established in 1944, has been collectively bargaining with Boeing uninterrupted since 1946. Originally a plain-and-simple single employer union with a narrow focus on wages, benefits, and working conditions, SPEEA was bothered by the militant strikes of blue-collar Boeing workers in the International Association of Machinists (IAM) District Lodge 751, and the organization began changing as the twentieth century ended. SPEEA entered the mainstream of organized labor by affiliating with the International Federation of Professional and Technical Engineers (IFPTE) in 1999 to end jurisdictional attacks from the IAM and the Teamsters unions.30

This new institutional direction and Boeing’s intransigence at the bargaining table produced fireworks. In the spring of 2000, SPEEA waged and won the largest white-collar worker strike in US history—17,000 out of 22,000 union-covered workers walked out for forty days—at Boeing in the Seattle metro area.31 The engineers and technical workers picketed and chanted “No Nerds, No Birds,” winning their wage and healthcare demands and shifting the union consciousness of its somewhat skeptical membership. SPEEA followed the strike that summer by winning a 4,200 worker union recognition campaign in Wichita, Kansas (hardly a labor stronghold), one of the most impressive private sector organizing wins in the twenty-first century.32 The vote count was 1,924 to 1,859, a stunning 90 percent voter turnout. In the same period, the Communications Workers of America (CWA) had some organizing successes in tech with IBM workers and Microsoft contractors through a direct action pre-majority union model, but complete union recognition victories remained elusive.33

Following SPEEA’s successful organizing of the strike and for recognition in Wichita, the IAM District Lodge 751, then with 26,000 blue-collar Boeing workers, decided to take on the task of organizing 17,195 non-union white-collar Boeing workers, beating SPEEA to the ballot. They failed.34 And the IAM failed catastrophically: also on a high 90 percent voter turnout, workers voted down the union 13,142 to 2,329 in July 2001. This remains the largest twenty-first-century National Labor Relations Board election to this day. Boeing’s recent labor relations have only gotten worse: IAM’s Washington membership is back down to around 26,000 workers following a recent cutting of five thousand workers (20 percent of its membership), and the manufacturer opened up a plant in union-hostile Charleston, South Carolina, thus keeping the shops free of unions by shifting production from Northwest to Southeast.35 The inability for SPEEA, IAM, or CWA to win further union recognition campaigns was a sign that this window of opportunity for a STEM worker uprising was quickly shut. In the last few years, though, Apple workers have unionized, Microsoft surprisingly announced that they would be collaborative with unions, and CWA has ported the IBM and Microsoft organizing model into its present Google-focused Alphabet Workers Union affiliate, bringing us back to the present, where a strong strategy of thorough worker organization during this rare STEM worker upsurge can also produce shifts in power.36

Today, what does on-the-ground organizing of STEM workers look like? How might this wave grow to transform STEM workplaces and society at large? Graduate student workers are a powerful force in the latest resurgence of labor organizing; these STEM workers work two to five (or more) years in a position billed as “primarily educational” by higher education institution administrators. But in reality, the typical STEM graduate student functions as a full-time researcher, with expectations to work forty-plus hours per week to produce results that bring prestige and money to the institution.37 As STEM graduate workers toil away in the lab, their student statuses are unjustly used by institution administrators as justifications for compensation and benefits that fail to meet their material needs. The rhetorical tactic of employers is not new; SPEEA and FAECT had to fight claims that they were not workers because of their job titles, and their histories show the necessity of workplace militancy to win decent working conditions and progress toward a transformative vision to make gains beyond economics.

Tensions between the purported educational experience and the reality of graduate student work sparked recent labor organizing at Georgetown University, a religious, private institution in Washington, D.C. Here, graduate student workers in the Biology PhD program have been key members of the cross-departmental coalition that formed the graduate labor union, the Georgetown Alliance of Graduate Employees (GAGE), affiliated with the American Federation of Teachers (AFT). At the time of writing in spring 2022, 100 percent of the Biology PhD students are GAGE members, and Biology members have high participation rates at every union meeting and on each committee and council. This was not automatic nor immediate; it took hundreds of one-on-one conversations, ongoing recruitment, and organizers’ dedication to inclusivity and transparency for over nearly a decade.

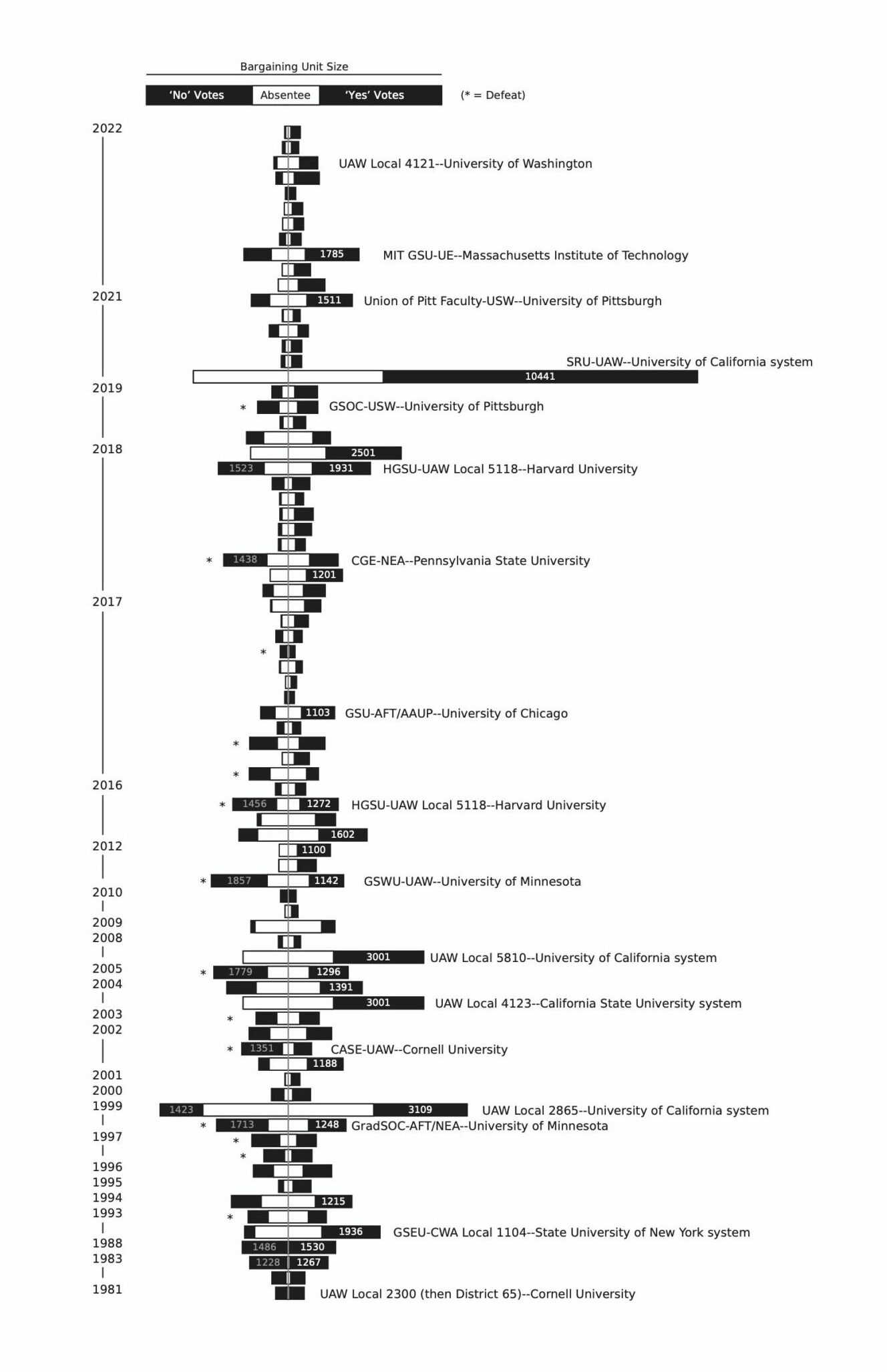

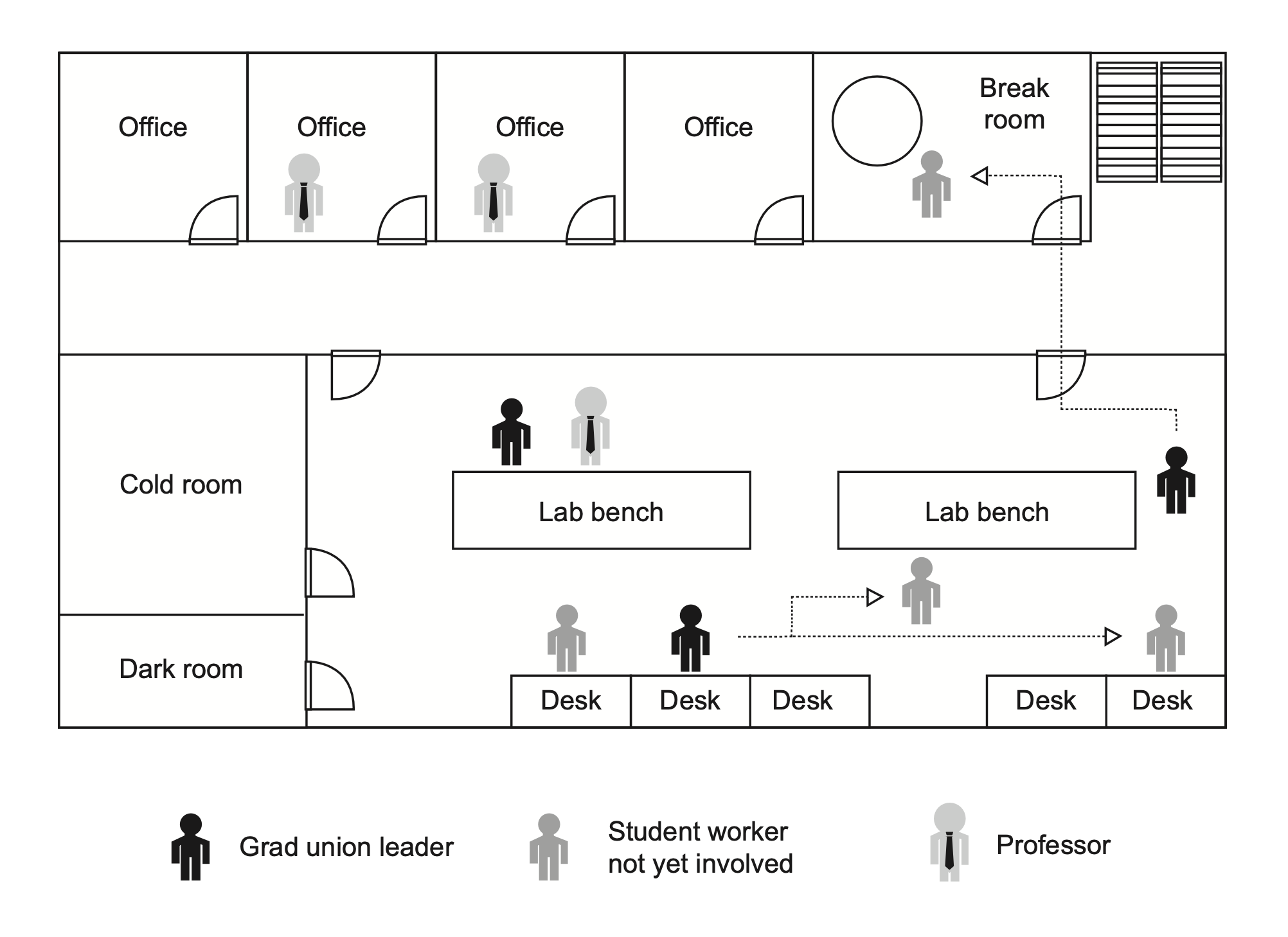

In the years leading up to the successful GAGE certification election in November 2018, only one or two Biology PhD workers were involved in organizing GAGE—-colleagues in humanities departments recruited them. To further grow membership in the Biology PhD program, the Biology worker organizers had to be empowered to take the lead, using organizing tools (workplace maps, wall charts, solidarity petitions, etc.; see figure 3 , volunteering to provide a GAGE update at every single Biology Organization of Graduate Students meeting, and most importantly, having one-on-one organizing conversations.38 Such conversations allowed space for fellow Biology graduate workers to share the issues that motivated them and to safely express any hesitation that held back their support or “stepping-up” involvement. In this one-on-one context, Biology organizers built a foundation of trust. They created a community that addressed the concerns of Biology PhD students with the broader GAGE organizing mission.

Issues that motivate GAGE members in the Georgetown Biology PhD program–compensation and benefits to live comfortably on; safe and fair working conditions; and a desire to make a scientific research career more accessible for the next generation, especially for those from historically excluded groups–are not unique. The drive to improve conditions for all by centering on the most vulnerable fellow student workers in Biology and other departments strongly motivated the Biology members to step up as organizers and committee members during GAGE’s first contract campaign. Then, in bargaining, Biology members saw their issues visibly and transparently discussed at the negotiations table, where the openness further encouraged high member participation. It was the collective effort of all to win, in the first contract, PhD stipend raises ranging from twelve to 14.5 percent, dental insurance, and a new Emergency Assistance Fund–the gains would be enjoyed by all.39

After the first contract wins, Biology workers have further spearheaded action on racial justice, housing justice workshops, and debt cancellation through GAGE.40 These emerging efforts to link GAGE to a broader vision for social transformation indicate that the new generation of student worker organizers is developing a movement akin to FAECT. Ultimately, Georgetown student workers will move on to other positions—such is the nature of students in graduate school—and take with them organizing skills and a commitment to solidarity with other workplaces. There, they are likely to be joined by alumni graduate organizers from higher education institutions across the country who are ready to continue the fight for just workplaces and an equitable society.

The current tide of STEM organizing shows no immediate signs of receding and presents a new and rare opportunity to reshape federal labor policy. The issues that motivate academic scientists to organize are also impacted by funding policies set forth by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Science Foundation (NSF), and Department of Energy (DOE). These policies can be targeted to improve labor conditions at higher education institutions in all departments. Broader public policy can also be changed through similar tactics to what we have been putting into action at our institutions: one-on-one conversations to engage the people impacted, democratically developing proposals, and mass mobilizing to pressure decision makers to adopt our proposals. Unionized scientists need to coordinate across institutions and the state to fight for better working conditions. The new Higher Education Labor United (HELU) coalition, composed of more than 110 organizations representing 550,000 plus workers, is the foundation upon which this work can grow.41

While the actions of the FAECT, UAW, UE, USW, SPEEA, CWA, AFT, etc., are extraordinary, they were done by ordinary people. For their victories to last, we must follow their examples and organize STEM workers massively, continuously.

Back to Contents

Notes

- Natalie Whitis, “Grad Student Researchers Win Battle for Union Recognition,” Synapse, December 16, 2021, https://synapse.ucsf.edu/articles/2021/12/16/grad-student-researchers-win-battle-union-recognition; Annelise Hanshaw, “UC Rejects One-Third of Student Researchers Union,” Santa Barbara News-Press, September 7, 2021, https://newspress.com/uc-rejects-one-third-of-student-researchers-union/.

- Typically university STEM workers are funded by a federal grant at the level of the individual (often called “fellows”) or the laboratory (often called research “associates” or “assistants”).

- The 65 percent figure was arrived at by dividing the number of votes cast by the number of eligible voters. Jonas Kaufman et al., “Breaking: 10,622 Student Researchers Vote to Authorize a Strike,” Student Researchers United, November 20, 2021, https://studentresearchersunited.org/breaking-10622-student -researchers-vote-to-authorize-a-strike- %f0%9f%a4%a0/; Trent McDonald, “Large (4,000+ Workers) US Union Recognition Campaign Data, 1990-2022,” Resources, WashU Undergraduate & Graduate Workers Union, accessed May 22, 2022, https://wugwu.org/resources/graduate-and-undergraduate-student-unions; Hannah Muniz, “How Many College Students Are in the U.S.?,” Best Colleges, March 22, 2022, https://www.bestcolleges.com/news/analysis/2021/03/22/how-many-college-students-in-the-us/; Phoebe Wall Howard, “UAW Gets More than 10,000 Signatures to Organize 10 University of California Campuses,” Detroit Free Press, May 24, 2021, https://www.freep.com/story/money/cars/2021/05/24/student-researchers-united-uaw-uc/5238888001/.

- Rebecca Johnson, et al., “Pitt faculty vote to form union by wide margin,” The Pitt News, October 19, 2021, https://pittnews.com/article/167927/featured/pitt-faculty-vote-to-form-union-by-wide-margin/.

- Trent McDonald, “Student Labor/Union Strike Data,” May 23, 2022, https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/ u/0/d/19uRwlUKq_NbVjUlxfbZimUGLq1lJnygfIpGW9VE1XUg/edit.

- Shelley Choi, “MIT graduate students vote to unionize, 66% in favor,” The Tech, April 8, 2022, https://thetech.com/2022/04/08/grad-students-unionize; Luis Feliz Leon, “Amazon Workers on Staten Island Clinch a Historic Victory,” Labor Notes, April 1, 2022, https://labornotes.org/2022/04/amazon-workers- staten-island-clinch- historic-victory.

- Admin, “‘Thrilled’ UW Researchers Vote Union YES!,” The Stand, June 10, 2022, https://www.thestand.org/?p=109065.

- “Union Members — 2021,” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, January 20, 2022, https://www.bls.gov/news. release/pdf/union2.pdf.

- Jimmy Settles, “Unions and the Fight for Civil Rights,” The Detroit Free Press, February 23, 2016, http://www.freep.com/story/opinion/contributors/2016/02/23/ unions-and-fight-civil-rights/80796098/; Trent McDonald and Jonah Furman, “Academic Workers Join Push for One Member, One Vote in the UAW,” Labor Notes, November 5, 2021, https://labornotes.org/blogs/2021/11/academic-workers-join-push- one-member-one-vote-uaw; Jane Slaughter, “United Electrical Workers Celebrate 75 Turbulent Years,” Labor Notes, September 30, 2011, https://labornotes.org/blogs/2011/09/united-electrical-workers-celebrate- 75-turbulent-years; Hannah Dourgarian, “K-swoc Files with the NLRB for Union Certification Election,” The Kenyon Collegian, October 21, 2021, https://kenyoncollegian.com/news/2021/10/k-swoc-files-with-nlrb-for- union-certification-election/; Gino Gutierrez, “UNM Grad Union Completes Card Count,” KSFR Santa Fe Public Radio, December 18, 2021, https://www.ksfr.org/post/unm-grad-union-completes-card-count #stream/0; Miranda Cyr, “State Certifies New Mexico State University Graduate Student Worker Union,” Las Cruces Sun-News, May 6, 2022, https://www.ksfr.org/post/unm-grad-union-completes- card-count#stream/0; Patrick McGerr, “IU Graduate Workers Submit Cards, Seek Union Election,” Herald Times, December 13, 2021, https://www.heraldtimesonline.com/story/news/local/2021/12/13/iu-graduate-workers-clear-hurdle- before-union-election/6477037001/.

- J.C. Pan, “There Is No Such Thing as a Conservative Workers’ Movement,” The Nation, September 11, 2020, https://newrepublic.com/article/159338/american-compass-conservative-workers-unions-labor; David Yaffe-Bellany, “GASO, an Anti-local 33 Group, Revives,” Yale Daily News, October 12, 2016, https://yaledaily news.com/blog/2016/10/12/135584/.

- Katherine Silliman, “Hesitation About Unionization,” The Chicago Maroon, October 16, 2017, https://www.chicagomaroon.com/article/2017/10/16/ graduate-students-skeptical-unionization-efforts/; namu, “What Are the Pros and Cons of Well Compensated STEM Graduate Students Joining a Union?,” Academia Stack Exchange, May 24, 2017, https://academia.stackexchange.com/questions/89955/what-are-the-pros- and-cons-of-well-compensated- stem-graduate-students-joining-a.

- “Employment in STEM occupations,” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, June 3, 2022, https://www.bls.gov/emp/tables/stem-employment.htm; “Union Members — 2021,” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

- Jake Bittle, “This University Suggested International Students Could Be Reported to ICE if They Unionized,” The Nation, October 5, 2017, https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/this-university- suggested-international-students-could-be-reported-to-ice-if-they-unionized/; Bill Schackner, “Is Fear over Visa Status Being Used to Derail Penn State Unionization Effort?,” The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 12, 2018, https://www.post-gazette.com/news/education/2018/04/12/Penn-State-University-graduate-students-international-students-visas-labor-Pennsylvania/stories/201804120153.

- Celine McNicholas, et al., “Unlawful: U.S. employers are charged with violating federal law in 41.5% of all union election campaigns,” Economic Policy Institute, December 11, 2019, https://www.epi.org/publication/ unlawful-employer-opposition-to-union-election-campaigns/.

- Harvard Graduate Students Union (HGSU), “After Two Years, We Have Secured Major Protections & a Solid Foundation for Our Union!,” June 2020, https://web.archive.org/web/20220113142149/https://harvardgrad union.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Contract-highlights-20200615.pdf; Georgetown Alliance of Graduate Employees (GAGE), “Workload and Time-off Policies,” https://www.wearegage.org/workload-time-off; UAW Local 5810, “UAW 5810 Victories Infographic,” May 2018, https://uaw5810.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/ UAW5810_VictoriesInfographic_0427.png; UAW Local 5810, “Compare How a Union Contract Improves the AR Experience,” June 2020, https://uaw5810.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/UAW_AR_Union_Contract _Improves_Experience_v4-1.pdf; UW Researchers United, “How a Union Contract Improves the Research Experience,” https://uwresearchersunited.org/union-contract/; UAW Local 2865, “Contract Highlights,” https://uaw2865.org/know-your-rights/contract-highlights/; Zukhra Kasimova, “International Student Workers Key to Chicago Grad Strike Victory,” Labor Notes, August 22, 2019, https://labornotes.org/2019/04/ international-student-workers-key-chicago-grad-strike-victory.

- Alexandra Jane, “Netflix Lays Off Women of Color as Stock Plummets,” The Root, April 30, 2022, https://www.theroot.com/netflix-lays-off-women-of-color-as-stock-plummets-1848864621; Alphabet Workers Union, “Google Employees Launch Petition Calling Foul as Google Cloud Support Announces Layoffs,” Alphabet Workers Union-CWA Local 1400, March 14, 2022, https://alphabetworkersunion.org/press/ releases/google-cloud-support-layoffs/; Christine Hall and Alex Wilhelm, “Robinhood to lay off 9% of full-time employees,” Tech Crunch, April 26, 2022, https://techcrunch.com/2022/04/26/robinhood-to-lay-off-9-of-full- time-employees/; Annalee Armstrong, “Fierce Biotech Layoff Tracker: Atreca culls workforce in reorganization; Athersys makes huge cuts,” Fierce Biotech, June 3, 2022, https://www.fiercebiotech.com/ biotech/fierce-biotech-layoff-tracker-2022.

- Matt Egan, “A major recession is coming, Deutsche Bank warns,” CNN Business, April 26, 2022, https://www.cnn.com/2022/04/26/economy/inflation-recession-economy-deutsche-bank/index.html; Daniel Kuehn, “The NIH funding crisis is really a biomedical research workforce crisis,” Urban Institute, May 6, 2015, https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/nih-funding-crisis-really-biomedical-research-workforce-crisis.

- Junyi Chu and Yanwei Wang, “International Student Workers Deserve Fair Treatment,” The Tech, November 18, 2021, https://thetech.com/2021/11/18/international-students-gsu; Ege Yumusak, “#MeToo’s Strike Test: The Harvard Graduate Student Union and the Limits of ‘Time’s Up’ Organizing,” The Drift, June 24, 2020, https://www.thedriftmag.com/metoos-strike-test/; Sherry E. Moss and Morteza Mahmoudi, “Stem the Bullying: An Empirical Investigation of Abusive Supervision in Academic Science,” eClinicalMedicine 40, (September 2021), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/ S2589537021004016; Meggan J. Lee et al., “‘If You Aren’t White, Asian, or Indian, You Aren’t an Engineer,’: Racial Microaggressions in STEM Education,” International Journal of STEM Education 7, (September 2020), https://stemeducationjournal .springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40594-020-00241-4; Cara Nixon, “STEM at OSU: Sexism Persists,” The Corvallis Advocate, January 16, 2021, https://www.corvallisadvocate .com/2021/stem-at-osu-women-still-harassed/; jayzmd, “American STEM Research: Rooted in Immigrant Exploitation,” Millennial Asian, December 30, 2017, https://millennialasian.com/2017/12/30/stem- exploitation/; Zipporah Osei, “Professor Resigns Amid Accusations That He Exploited Grad Students With ‘Modern Slavery,’” The Chronicle of Higher Education, January 16, 2019, https://www.chronicle.com/article/ professor-resigns-amid-accusations-that-he-exploited-grad-students-with-modern-slavery/.

- Chris Woolston, “The Mental Health of PhD Researchers Demands Urgent Attention,” Nature, November 13, 2019, https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-03489-1; Teresa M. Evans, et al., “Evidence for a Mental Health Crisis in Graduate Education,” Nature Biotechnology 36, (March 2018), https://www.nature.com/articles/ nbt.4089.

- Vincent Larivière, et al., “Investigating the division of scientific labor using the Contributor Roles Taxonomy (CRediT),” Quantitative Science Studies 2, no. 1 (April 2021), https://direct.mit.edu/qss/article/2/1/111/97558/Investigating-the-division-of-scientific-labor.

- Michael Goldfield and Cody R. Melcher, “Moments of Rupture: The 1930s and the Great Depression,” Convergence, November 9, 2021, https://convergencemag.com/articles/moments-of-rupture-the-1930s- and-the-great-depression/.

- Trent McDonald, “Why Sectoral Bargaining Matters for the Labor Movement,” Jacobin, July 4, 2021, https://jacobin.com/2021/07/sectoral-national-industry-wide-bargaining-contracts-us-unions.

- Robert Heifetz, “The Role of Professional and Technical Workers in Progressive Social Transformation,” Monthly Review, December 1, 2000, https://www.thefreelibrary.com/The+Role+of+Professional+and+ Technical+Workers+in+Progressive+Social…-a068647937; Jasmine Kerrissey and Judith Stepan-Norris, “Lessons from Manufacturing in the 1930s,” The Forge, March 24, 2022, https://forgeorganizing.org/article/lessons-manufacturing-1930s; Staughton Lynd, We Are All Leaders: The Alternative Unionism of the Early 1930s (University of Illinois Press, 1996); Barry Eidlin and Micah Uetricht, “The Problem of Workplace Democracy,” New Labor Forum 27, no. 1 (Winter 2018), https://www.jstor.org/stable/26420120; Eric Dirnbach, “Why Is the Workplace a Dictatorship?,” Organizing Work, September 12, 2019, https://organizing.work/2019/09/why-is-the-workplace-authoritarian/.

- Shannan Clark, The Making of the American Creative Class: New York’s Cultural Workers and Twentieth-Century Consumer Capitalism (Oxford University Press, 2020); Matt Bodie, “What If I Told You that Employer Power Is a Legal Construct?,” Worklaw Jotwell, November 26, 2021, https://worklaw.jotwell.com/what-if-i-told-you-that-employer-power-is-a-legal-construct/; “Union Rights – Management Rights – Recognition Clause,” UE Steward, February 2017, https://www.ueunion.org/ stwd_rcl.html; Mardges Bacon, “The Federation of Architects, Engineers, Chemists and Technicians (FAECT): The Politics and Social Practice of Labor,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 76, no. 4 (December 2017): 454–463, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26419049.

- Jeff Schuhrke, “To Build a Left-Wing Unionism, We Must Reckon With the AFL-CIO’s Imperialist Past,” In These Times, January 10, 2020, https://inthesetimes.com/article/left-wing-union-afl-cio-imperialism.

- Bacon, “The Federation of Architects, Engineers, Chemists and Technicians (FAECT).”

- Trent McDonald, “Left, Center & Right CIO Unions,” Resources, Graduate and Undergraduate Student Unions, accessed June 3, 2022, https://wugwu.org/resources/graduate-and-undergraduate-student-unions; Judith Stepan-Norris and Maurice Zeitlin, Left Out: Reds and America’s Industrial Unions (Cambridge University Press, 2003).

- Joe Burns, “For Inspiration, Look to the History of Public Worker Strikes,” Labor Notes, June 18, 2014, https://labornotes.org/2014/06/inspiration-look-history-public-worker-strikes.

- Lisa Phillips, “The Forgotten Union,” Jacobin, August 10, 2016, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2016/08/ unions-low-wage-service-sector-new-york-labor/; Tamiment Staff, “Guide to the United Automobile Workers of America, District 65 Records,” Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, July 1, 2019, http://dlib.nyu.edu/findingaids/html/tamwag/wag_006/bioghist.html.

- Ross Rieder, “SPEEA Union (Society of Professional Engineering Employees in Aerospace),” HistoryLink, March 30, 2020, https://www.historylink.org/File/2211.

- Ron Wanttaja, “The Boeing Strike: A Report from the Trenches,” AVweb, February 23, 2000, https://www.avweb.com/features/the-boeing-strike-a-report-from-the-trenches/; Sam Howe Verhovek, “Tentative Pact Made to End Boeing Strike,” New York Times, March 18, 2000, https://www.nytimes .com/2000/03/18/business/tentative-pact-made-to-end-boeing-strike.html.

- “Boeing Wichita Workers Narrowly Approve Retaining Union,” Puget Sound Business Journal, February 13, 2004, https://www.bizjournals.com/seattle/stories/2004/02/09/daily37.html.

- “IBM Employees and CWA Launch Alliance@IBM,” Communications Workers of America, October 1, 1999, https://cwa-union.org/news/entry/ibm_employees_and_cwa_launch_allianceibm; “WashTech Fights for ‘Permatemps’ on Three Fronts,” Communications Workers of America, March 1, 1999, https://cwa-union.org/news/entry/washtech_fights_for_permatemps_on_three_fronts; E. Tammy Kim, “Do Today’s Unions Have a Fighting Chance Against Corporate America?,” New York Times, February 17, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/17/magazine/unions-amazon.html.

- Nevin E. Adams, “Admin/Professional Boeing Workers Reject Union,” Plansponsor, July 23, 2001, https://www.plansponsor.com/adminprofessional-boeing-workers-reject-union/.

- Dominic Gates, “Boeing Job Cuts Will Fall Heavily on Engineers and Machinists,” Seattle Times, May 29, 2020, https://www.seattletimes.com/business/boeing-aerospace/boeing-job-cuts-will-fall-heavily-on- engineers-and-machinists/; David Wren, “Boeing’s North Charleston Workers Vote against Machinists Union Representation,” The Post and Courier, February 15, 2017, https://www.postandcourier.com/business/ boeings-north-charleston-workers-vote-against-machinists-union-representation/article_785f3b30-f3b3-11e6-b13e-b75e5147c25a.html; Eric M. Johnson, “Boeing to Move 78 Production to South Carolina in 2021,” Reuters, October 1, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/boeing-787-idUSKBN26N08Y.

- Katharine Schwab, “‘We’re the Ones Making Google the Money’: 2 Alphabet Union Workers on Why They Organized,” Fast Company, January 5, 2021, https://www.fastcompany.com/90590849/alphabet-workers- union-google-organizers; Laura Rosenblatt, “Microsoft President Says Employees ‘Will Never Need To’ Unionize,” Seattle Times, June 3, 2022, https://www.seattletimes.com/business/unprompted-microsoft -says-employees-will-never-need-to-unionize/; Amrita Khalid, “Apple Attempts to Appease Union Efforts with Scheduling Improvements,” Engadget, June 3, 2022, https://www.engadget.com/apple-unveils-new-rules-on- working-hours-for-retail- employees-003058468.html.

- Noam Scheiber, “Grad Students Win Right to Unionize in an Ivy League Case,” New York Times, August 23, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/24/business/graduate-students-clear-hurdle-in- effort-to-form-union.html; Marissa Knoll, “Graduate Students Do Real Work. Let Us Unionize,” Salon, December 8, 2019, https://www.salon.com/2019/12/08/graduate-students-do-real-work-let-us-unionize _partner/.

- Alexandra Bradbury et al., “Secrets of a Successful Organizer Handouts,” January 1, 2016, Labor Notes, https://labornotes.org/secrets/handouts; GAGE, “A Contract for the Whole Person,” Thrive Pledge, accessed August 1, 2022, https://www.wearegage.org/our-pledge.

- Jewel Tomasula and Daniel Solomon, “Contract Personalis: How Georgetown’s Graduate Workers Organized to Win,” The Forge, October 5, 2020, https://forgeorganizing.org/article/contract-personalis- how-georgetowns-graduate-workers-organized-win; GAGE, “Highlights of Our First Union Contract,” May 1, 2020, https://www.wearegage.org/contract-2020.

- GAGE, “GAGE Recap: Racial Justice,” EnGAGE!@AFT (blog), July 11, 2020, https://medium.com/engage-aft/gage- recap-racial-justice-4aca5ccfe6e3.

- Aimee Loiselle et al., “Higher Ed Labor Unites for Equity for All: Faculty, Staff and Students,” Convergence, April 2, 2022, https://convergencemag.com/articles/higher-ed-labor-unites-for-equity-for-all- faculty-staff- and-students/.