The Science of Woman, Life, Freedom: Jineolojî

By Targol Mesbah

Volume 26, no. 1, Gender: Beyond Binaries

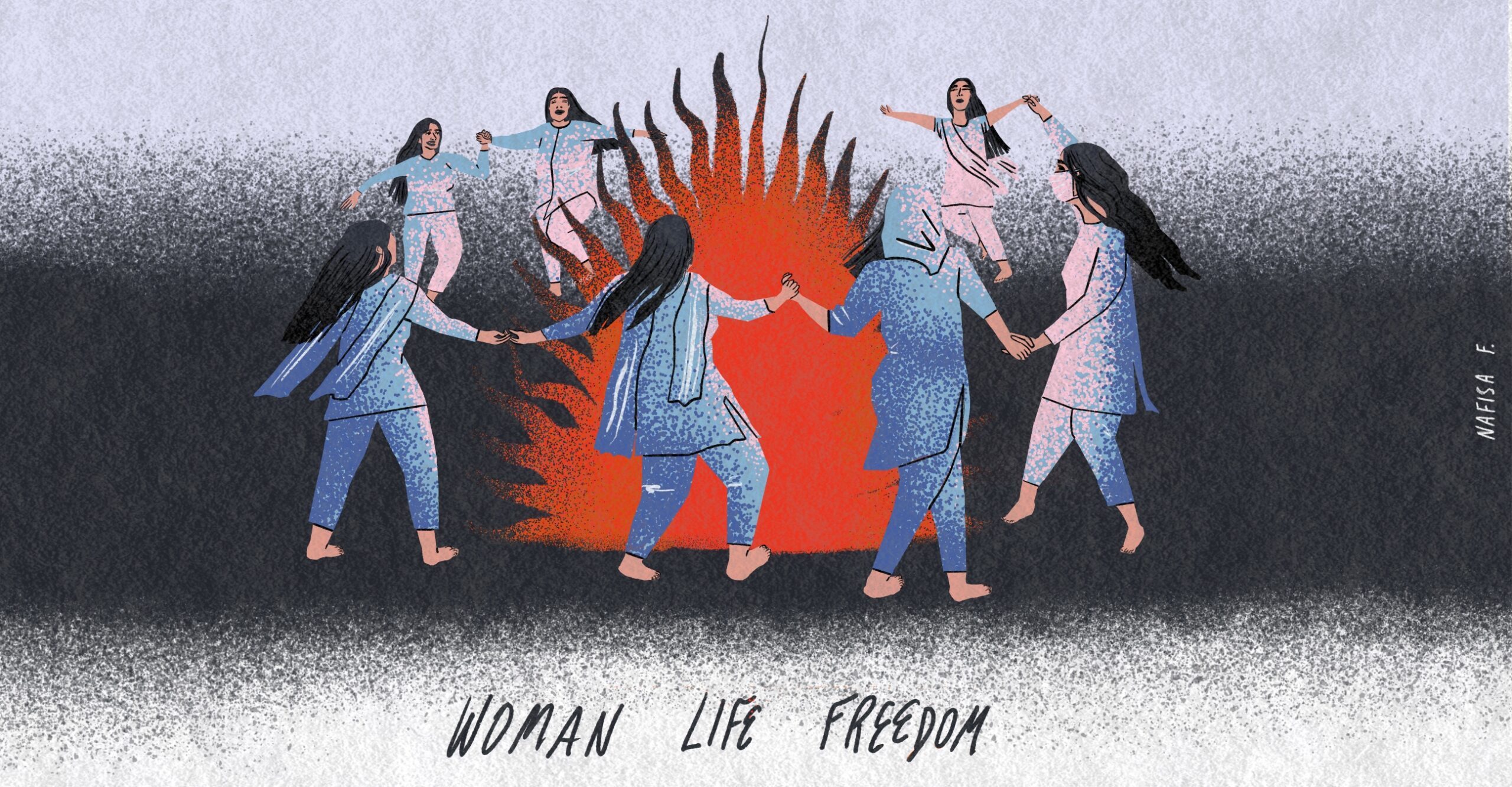

The current revolutionary movement sidelines the western liberal democratic discourse on the need to save Muslim women and is calling for a total reorganization of the social fabric of life

In the Kurdish language, jin means woman and shares the same root with jiyan, or life. As a “science of woman,” Jineolojî engages every aspect of the reproduction of life itself. It is rooted in the Kurdish freedom movement and seeks to challenge and transform patriarchal, capitalist, and colonial systems of oppression. Jineolojî is considered a science because it involves a systematic study and analysis of women’s history, empirical experiences of women’s autonomous organizing, as well as their contributions to various theoretical and practical traditions in service of the liberation of women, understood as the liberation of all of society. As a critical framework, Jineolojî critiques the primacy of scientific positivism in reducing complex social phenomena to measurable and quantifiable data, ignoring the contradictory, contextual, intuitive, and subjective aspects of human experience. Jineolojî argues that this reductionist approach fails to capture the nuances and diversity of women’s lives, struggles, and knowledge, which are often marginalized or made invisible.

The term Jineolojî was first proposed in 2008 by the movement’s leading figure, Abdullah Öcalan, and informed by years of women’s organizing within the Kurdish freedom movement.4 Öcalan founded the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in the 1970s and has been a political prisoner in the Turkish island prison of Imrali since 1999. Under Öcalan’s leadership, the PKK experienced a paradigm shift between the mid 1990s to 2005, transforming from a Marxist-Leninist organization seeking an independent Kurdish state to a non-state-based movement for a confederate network of local and regional self-governing zones. His writings have been taken up by horizontalists, anarchists, indigenous communities, and others with affinities for a world based in mutual aid and reciprocity. In addition to offering a grounded praxis for autonomous organizing in this time of civilizational and planetary crisis,5 Öcalan’s historical analysis of the state’s emergence in the ancient city-state of Sumer in Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq) is consequential for Jineolojî and revolutionary movements today. According to Öcalan, the rise of the state was accompanied by the development of a hierarchical social order, with men assuming positions of power and authority over women. Religious practices helped to provide a framework for social cohesion and to legitimize the patriarchal state’s control of resources, while the subjugation of women was seen as a necessary means of controlling reproductive labor.6

More specifically, according to Öcalan, woman was the first colony. All other forms of domination, including colonialism and capitalism, replicate this original relation of domination. The fundamental connection between woman and free life is the basic premise of Jineolojî as a science of woman. Given that patriarchy exercises control over the detailed arrangement of everyday life, every element of life colonized by patriarchy would have to unravel to free woman, and as a result, all life. While recognizing the proximity of woman to life, Jineolojî simultaneously rejects a biologically determined definition of woman. The category of woman is understood as a social phenomenon and the science of woman is a continuous process of collectively rearticulating a conception of woman within the social, not as a detached form of knowledge, but as a science, method, and knowledge for liberation. While building on the historical contributions of feminist critiques of patriarchy, Jineolojî proposes a new epistemology. Put differently, the open question of the meaning of woman is informed by the material analysis of women’s lived experiences in struggle for freedom and in a different context from western debates between biological determinism and social constructivism. Reimagining gender roles is an ongoing process and different in each context. It is not possible or desirable to define gender within this relational, collective, and internationalist science of woman and life. What is consistent is a nonessentialist and transformative relation to gender and patriarchy. Jineolojî’s historical and relational approach moves beyond binaries without necessarily using nonbinary as a gender category. Within the dynamics of an internationalist science that nonetheless emerges from the Kurdish freedom movement, new discussions continue to emerge and connect different lived experiences of gender in struggle.7

In The Kurdish Women’s Movement: History, Theory, Practice (2022), Dilar Dirik describes the shift from a Marxist-Leninist struggle for a Kurdish state to democratic confederalism as one of “feminizing revolution,” in part because the nation-state is seen as a fundamentally patriarchal form of arranging social, political, and economic relations.8 In contrast, democratic confederalism as practiced in Rojava, for example, is based on a number of assemblies, councils, committees, and academies. At the core of the council system are the neighborhood assemblies, which serve as the foundation for larger units of governance spanning from villages and city neighborhoods to canton and regional levels. One of the most significant achievements of the Rojava Revolution has been the establishment of autonomous women’s councils. These councils are responsible for ensuring that women’s rights are respected and that women are represented in all levels of government and decision-making. In addition to equal gender participation, each level of governance has its own women’s council with the power to veto any decision that may adversely affect women.

The paradigm of democratic confederalism also advocates for a different perspective on revolutionary change, where the reorganization of social life is not seen as an immediate and complete rupture with the past. Instead, it is viewed as an ongoing struggle, spanning a prolonged period, aimed at establishing new and enduring social relations that permeate all aspects of everyday life. In this context, the role of academies is crucial for autonomous education that disrupts the patterns of patriarchal and capitalist subjectivities. The Jineolojî Academy, for example, is part of the University of Rojava and develops specific curricula and popular education programs outside the university. These programs have been an important site of unlearning internalized patriarchal norms and practices.

Jineolojî is a collective science of theorizing, analyzing, and practicing different emancipatory ways of knowing the world. A network of Jineolojî academies, committees, research centers, and conferences weaves together increasingly international participation from the four regions of Kurdistan to Belgium, Germany, France, and Sweden. Jineolojî, a quarterly journal of science and theory, has been published since 2016 out of Northern Kurdistan in Turkey. While the print publication is in the Turkish language, the Jineolojî website publishes online articles and videos in Arabic, Farsi, English, and other languages. The journal has also released an English language special edition. A shortened summary version of the book Introduction to Jineolojî has also been translated into English. Still, English language sources remain limited.9

the open question of the meaning of woman is informed by the material analysis of women’s lived experiences in struggle for freedom and in a different context from western debates between biological determinism and social constructivism

The science of woman runs through every aspect of life seeking to free itself from the patriarchal state and capitalist exploitation of humans and the earth. It is concerned with the preservation and promotion of traditional knowledge, as well as the development of new knowledge and perspectives that reflect the experiences of women in struggle. Some “areas of action” for research include ethics-aesthetics, economy, demography, ecology, history-herstory, health, education, and politics.10 The women’s village of Jinwar in Rojava, for example, is a project of the Jineolojî Academy where women and children live a communal life based on the principles of ecological sustainability and decentralized communal decision-making. Jinwar is a place of refuge for women of different ethnicities and language backgrounds who were widowed during the war with ISIS, or who otherwise left their families to participate in the building of the women’s commune. The thirty homes in this settlement were built with traditional mud bricks. There is a communal kitchen, a medical center that uses plant medicine grown in the village, gardens of fruit trees and vegetables, fields of wheat, and a bakery famous in the region for its delicious bread. Residents of Jinwar participate in regular meetings and assemblies, where they discuss and make decisions about issues affecting the village. Artworks throughout the village conjure the ancient mythological figure of Shahmaran, a nonbinary woman-serpent who is the keeper of the healing knowledge of the earth and herbal medicine. There is also an academy where residents learn about Jineolojî.11

Within the broader context of Jineolojî and democratic confederalism, it becomes clear that we cannot untangle the women-led uprising in Iran from economic, ethnic, and social concerns that affect the whole of society even as women’s oppression anchors all other forms of state domination. Revolutionary struggles are usually met with violence. The situation in Iran is intensifying with recent widespread release of poison gas in high schools across the country, likely to terrorize youth against participating in the direct actions celebrating their collective autonomy through song and dance.12 Jineolojî can help us see the creative revolutionary current of the women’s uprising in Iran and to prevent its containment within liberal feminist or colonial state politics.

What are the lessons of Jineolojî for Iran and for revolutionary struggles on and for the planet? This new and emergent science is collective, decentralized, and international, encouraging women everywhere to research, theorize, and share the recuperation of their own histories, local knowledges, and forms of autonomous organizing that has always existed, even if relegated to the shadows. In the Kurdistan province of Iran, where Jina Amini was from, there is a rich history of women’s autonomous organizing, including the Women’s Council of Sanandaj who created the first health clinics and libraries in 1979 to serve the local needs of the population.13 There are many other historical and living examples of such organizing from below, and Jineolojî asks us to collectively analyze and theorize these struggles and resistances. It is a science in-the-making and runs through all life.

—

Targol Mesbah teaches critical thinking and media studies in the Anthropology and Social Change department at the California Institute of Integral Studies. She was born and raised in Tehran, Iran and currently lives between Oakland and Los Angeles. She is an adherent to the Sixth Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle.

Notes

- Jineolojî Committee Europe, “What is Jineolojî?” Jineolojî: A Quarterly Journal of Science and Theory, special edition for English readers, https://jineoloji.org/en/2018/12/14/what-is-jineoloji/.

- b9AcE (@b9AcE), “From Funeral of Kurdish woman Mahsa Amini, from Saqqez in Rojhelat Kurdistan/NW Iran, murdered by ‘morality’ police of Tehran. ‘Jin! Jiyan! Azadi!’ (Women! Life! Freedom!) the classic feminist slogan of Kurdish liberation movement,” Twitter, September 17, 2017, https://twitter.com/b9ace/status/1571060404482342913.

- Eleonora Gea Piccardi and Stefania Barca, “Jin-jiyan-azadi: Matristic Culture and Democratic Confederalism in Rojava,” Sustainability Science 17 (2022): 1273–85.

- Abdullah Öcalan, Sociology of Freedom: Manifesto of the Democratic Civilization, Volume III (Oakland: PM Press, 2020); Dilar Dirik, The Kurdish Women’s Movement: History, Theory, Practice (London: Pluto Press, 2022).

- Influenced by social ecologist Murray Bookchin, Öcalan sees the degradation of the earth’s ecosystem as pivotal to how hierarchy works within capitalist modernity. See Murray Bookchin, The Ecology of Freedom: The Emergence and Dissolution of Hierarchy (Oakland: AK Press, 2005).

- Abdullah Öcalan, Prison Writings: The Roots of Civilisation, trans. Klaus Happel (London: Pluto Press, 2007); Joost Jongerden, “Gender Equality and Radical Democracy: Contractions and Conflicts in Relation to the ‘New Paradigm’ within the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK),” Anatoli 8 (2017): 233–56.

- “Open Letter to the Public: About the Article ‘Beyond Feminism? Jineolojî and the Kurdish Women’s Freedom Movement,” May 26, 2021, https://jineoloji.org/en/2021/05/10/open-letter-to-the-public/.

- Dilar Dirik, The Kurdish Women’s Movement.

- Jineolojî: A Quarterly Journal of Science and Theory, special edition for English readers, March 2020.

- Jineolojî Committee Europe, “Jineolojî,” Mezopotamien Verlag und Vertriebs, no. 2 (2018): https://jineoloji.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Jineolojî-English-v2-Final.pdf.

- Personal observations during my visit to Jinwar in June 2019 where I met with members of the Jineolojî Academy.

- Michele Catanzaro, “Suspected Iran Schoolgirl Poisonings: What Scientists Know,” Nature 615, 574 (2023): https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-00754-2.

- Fatemeh Karimi, Genre et Militantisme au Kurdistan D’Iran: Les femmes kurdes du Koomala 1979–1991 (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2022); Dancing for Change, directed by Shahrzad Arshadi (2015).