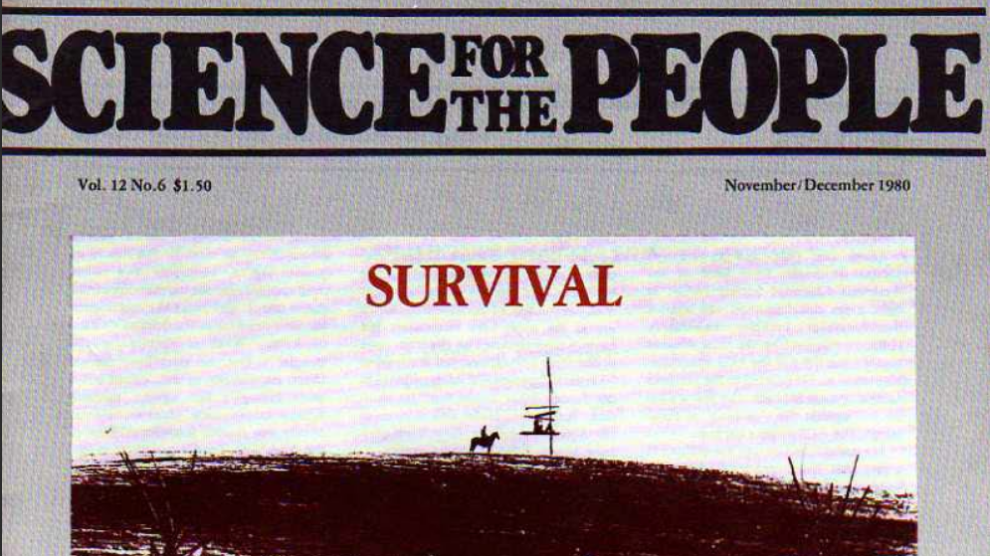

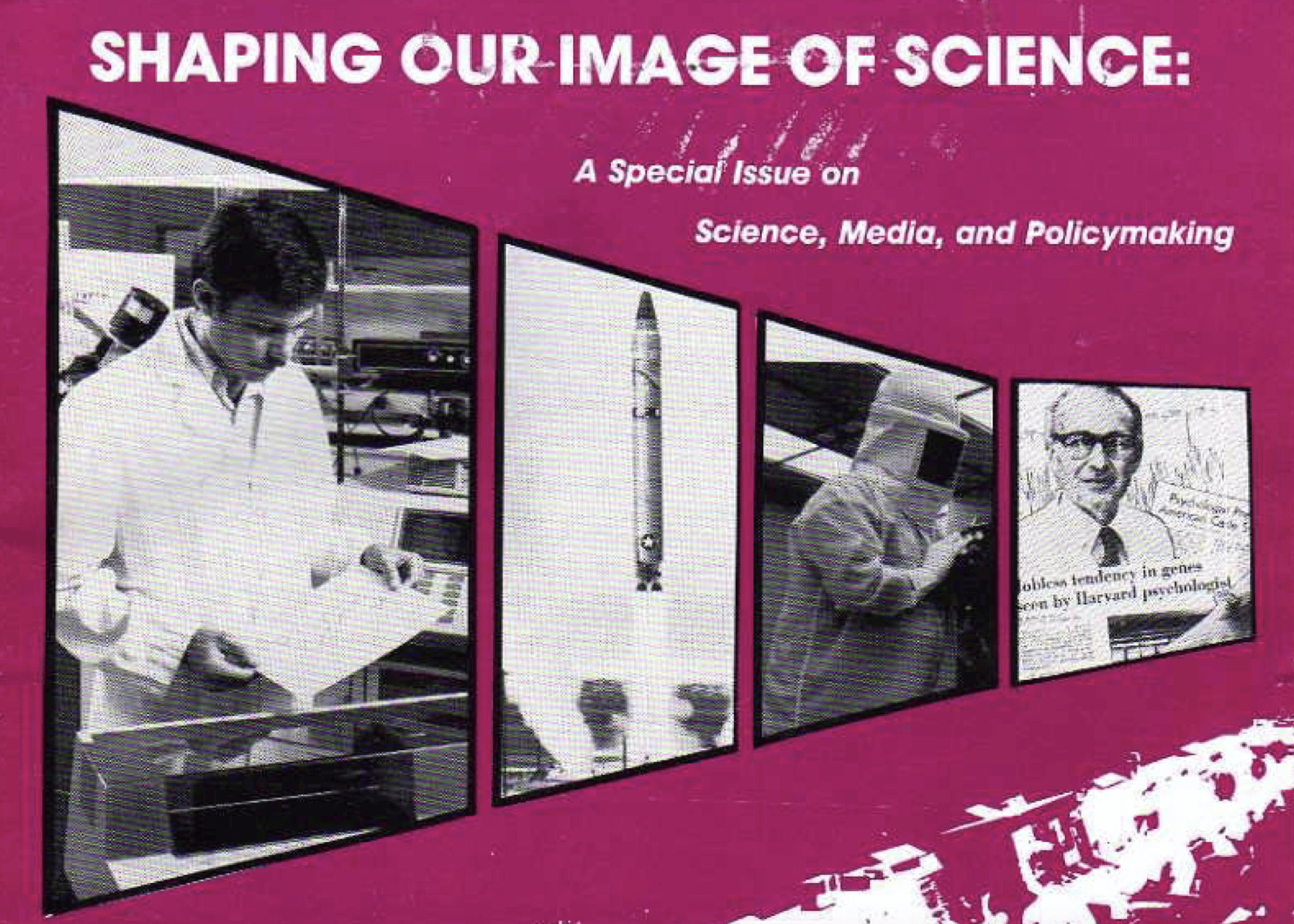

SftP Looks at Popular Science Magazines:

Archival Reprint: Science for the People Vol. 16, No. 4, July/August 1984, p. 30–31

By Seth Shulman

Volume 27, no. 1, Rethinking Science Communication

A trip through the science section of the newsstand could easily lead one to believe that solutions to all of our problems lie just around the corner. A recent sampling of magazine headlines included the following: “The Coming Cure for Cancer,” “How To Make Nuclear War Obsolete,” and “Satellite Rescues: A New Era Begins.” Unfortunately, a guided tour of popular science magazines reveals more about the magazines themselves than it does about our society’s rate of problem solving.

One would think that the devastating consequences which many scientific “breakthroughs” have wrought might cause headline writers to be at least somewhat more cautious. Living with the realities of nuclear power, chemical weapons, and toxic waste to name a few, one would think it to be very difficult today to hold the position that science and technology are neutral, that a scientific or technological discovery can be divorced from its impacts and implications, or that new technology will eventually solve all of our problems. Yet, to a disconcerting degree, these are exactly the claims one finds regularly in most of the popular science magazines.

In glossy magazines with titles like Discover, High Technology, and OMNI, with owners like the Hearst Corporation and Time, Inc., the coverage of such diverse fields as military technology, genetic engineering, and computer technology tend to take on a glaringly promotional tone about the potential of new technology to solve pressing social problems. In their efforts to market their products, editors of the popular science magazines seem to feel that only the breakthroughs, the new discoveries, will “sell” science and technology to the public. Consequently, articles in these magazines routinely steer away from more complex, substantive policy questions where the politics and uncertainty of science come into play. Topics such as what to do about water contamination, or the military funding of academic science will rarely, if ever, grace their pages. Perhaps even worse, when they are covered, the article will most likely make a claim that a simple solution is in the offing.

Such an attitude on the part of the media is misleading today, but it is all the more inexcusable in light of the historical record. In many ways such reporting is reminiscent of the unbridled high expectations during the earlyyears of nuclear power when the Eisenhower administration spoke of “Atoms for Peace,” and the media depicted the potential dangers and problems in a painfully naive way, focusing instead on how cheap electricity would be. Such a simplistic, wide-eyed attitude towards new technologies without regard to their social and political implications was hard to justify at that time; clearly we can’t afford it now. Nonetheless, it is still foisted upon us with an enthusiasm that might even be catchy if one hadn’t seen much the same claims last month and last year. Take, as a fairly random example, the cover story of the recent June 1984 Science Digest, Hearst Corporation’s entry into the popular science field (where, as they tell us “fact is more exciting than fiction’”). The headline reads, “How to Make Nuclear War Obsolete.” Provocative at a glance? Undoubtedly. But just how are we supposed to be able to accomplish such a feat? The article maintains that the answer lies in a dramatic technological fix, in this case the new breed of “smart warheads.” The idea that a new breed of weapons will solve the problem of nuclear war is not just bad politics, it is bad science.

Such hyperbole is hardly limited to military-related pieces, however. Articles covering computer technology so often fall prey to such a wide-eyed, promotional perspective that it is hard to find exceptions. While articles like: “Home Computer Power: Why You Need It,” and “Shirk the Drudgery of 9 to 5 with your Personal Computer” abound, any type of analysis beyond a comparison of two competing models is hard to find.

Supplementing the coverage in the major popular science magazines is that found in the huge number of popular computer magazines that have sprung up within the past five years. While most articles like the above are clearly geared to help the consumer find his or her way through the vast array of new products, the absence of any substantive critical analysis about the real potentials and limitations of computer technology is nothing less than irresponsible. Discussion of the problems of limited access to computers for low-income people, or of the very real obstacles to successful teaching through computers is noticeably lacking. Also absent is any coverage of the growing number of studies pointing to potential hazards from the low-level radiation that VDTs emit, hazards such as increased incidence of cataracts skin rashes, and problem pregnancies.

Upon reviewing coverage of science and technology by the major popular science magazines, there seem to be two major particularly offensive types of claims made about scientific and technological “breakthroughs.” One type is the claim which blatantly ignores the political realities which will inevitably shape the usage of the technology in question.

A powerful example of this first type of offensive coverage can be seen in an article on agricultural biotechnology published in the April 1983 Science Digest. The author, who teaches science writing at the college level, promotes agricultural biotechnology throughout the article in glowing terms: “Many of these genetic tricks, which were in the realm of sorcery only 10 years ago, appear attainable in the decades ahead because of several recent triumphs…” Triumphant though they may be, this particular author fails to devote even one sentence to the political realities of agricultural biotechnology.

Genetic engineering certainly holds tremendous potential in this field, but the corporate jockeying for ownership of the “supercrops” is already raising important fears of scientists and laypeople alike. Rather than simply laud the promise of “raising worldwide food production,” this author would have done well to examine exactly who will benefit from such technology and why a rapid diffusion of this particular technology for feeding the hungry of the Third World is highly unlikely and unrealistic.

The other type of offensive claim is that which is so taken by a particular example of technical mastery that perspective is lost of the ends to which such work is being put. A good example of this second type of offensive claims can be seen in an article from Science ’84 (published by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, as we are told, “to bridge the distance between science and citizen.”) This article from last year covered the proposed new Trident-11 missile, or as Science ’84 termed it, “the Next Superweapon.” According to the author, these missiles are “both invulnerable and capable, at least in theory, of destroying every nuclear weapon on enemy soil within 15 minutes.” Reporting like this should always raise questions. Is anything truly invulnerable? And what is the cost in human lives of this vast destruction of enemy nuclear weapons? While, in all fairness, the author does acknowledge some criticism of the new system, the main body of the article is devoted to a discussion of the increased accuracy of the new guidance system. The sophistication of this technology is undoubtedly cause for excitement, yet the glamorous portrayal seems to forget to what use this sophistication is going.

There is an unquestionable need for science journalists to chronicle the latest scientific and technological achievements; these achievements are also quite understandably, the cause for a good deal of awe and wonderment. It is dismaying, however, to see how often such a perspective leads to simplistic and plainly biased reporting. There have been too many dashed promises and vested interests, too many environmental hazards and waste by-products to justify the type of rhetoric prevalent in much of today’s popular science journalism.

We at SftP certainly realize that we are not above criticism ourselves, but hopefully the two types listed above will not come up often within these pages. Because of the dazzlingly large numbers of readers these magazines reach (each one alone has a circulation more than one hundred times as large as SftP), we feel all the more strongly the need for them to provide more critical analysis and less awe-struck, “star wars” science reporting. But until then, we at Science for the People will redouble our efforts. We know we have our work cut out for us.

—

Seth Shulman was the Magazine Coordinator for Science for the People at the time of this article’s original publication, and had various editorial and magazine roles in the 1980s.