Letter from the Editors

Volume 27, no. 1, Rethinking Science Communication

A capitalist context often makes it difficult to realize the ideals we have for radical science communication, and the articles in this issue address some of those difficulties. Commercial science journalism often serves as public relations for the latest technology or touts the latest medical advice, only to be soon replaced by something new to boost sales and distract the public’s attention from underlying social problems. This is science communication as profit-seeking, competition, and consumerism.

Several themes in this issue reveal the dialectical relationships between aspects of science communication, arising from such factors as the scales at which science communication operates, the emotional responses it elicits, the perspectives from which people evaluate and interpret it, and the relationships between researchers and those accessing or participating in their research. They also bring to light many challenges: in particular, a growing distrust in science by the general public. We recognize the importance of expertise, but at the same time seek to open up multi-directional channels of communication that allow the public to influence the direction of scientific research. This presents some necessary interrogation into determining best practices to approach communication around urgent issues pertinent to the public globally. For example, how do we as practitioners of science help people understand the dire situation posed by climate change and ecological degradation without succumbing to a paralysing sense of fatalism and futility? Navigating these tensions requires attention to the political, economic, and cultural context in which science operates, including the ideological separation of human society from more-than-human nature at the foundation of capitalist society.

How do we define the goals of radical science communication within, yet in opposition to, capitalism? Jackson Howarth explores communication that stimulates action on the critical issue of climate change. Pratyasha Nath and Jenia Mukherjee describe a successful project to integrate local agency and flourishing in the changing ecology of a remote village in the Sundarbans delta. Several other articles in this issue, including those by Alyssa Shearer and Silvio Paone, discuss the use and misuse of metaphor. Octopus camouflage is described in parallel with code-switching in Angelique Allen’s piece, while Anita Chandran outlines the ways in which fiction can expand scientific practices, engage audiences, and firmly situate science. While metaphors are essential linguistic tools for expressing new ideas, those such as viewing disease as caused by “invasion” of infectious agents (without regard to other health factors, such as the social and physical environment) or natural selection as “survival of the fittest” are dangerously misleading; they reflect, and serve to reinforce, social relations based on domination and competition.

The authors of these articles share insights into their experiences working towards radical approaches to science communication. They discuss good faith efforts to subvert the conventional deficit model of science communication, which envisions the scientist as the active communicator and the public as the passive audience. In its place, we see examples of multi-sided exchanges of knowledge, where scientists and communities are in dialogue and where both parties are invited to participate in the co-creation of knowledge. Speaking to their experiences, the pieces also identify some challenges and difficulties that can arise, related to funding constraints, scaling, power imbalances, and the problems of transferring insights gained from earlier radical models of participatory science into decidedly less radical contexts. While we see glimpses of promising alternatives based on multidirectional communication and the opening up of processes that are too often undertaken behind closed doors and out of public view, we must also be cognizant of the limits of calls for simply more participation and dialogue.

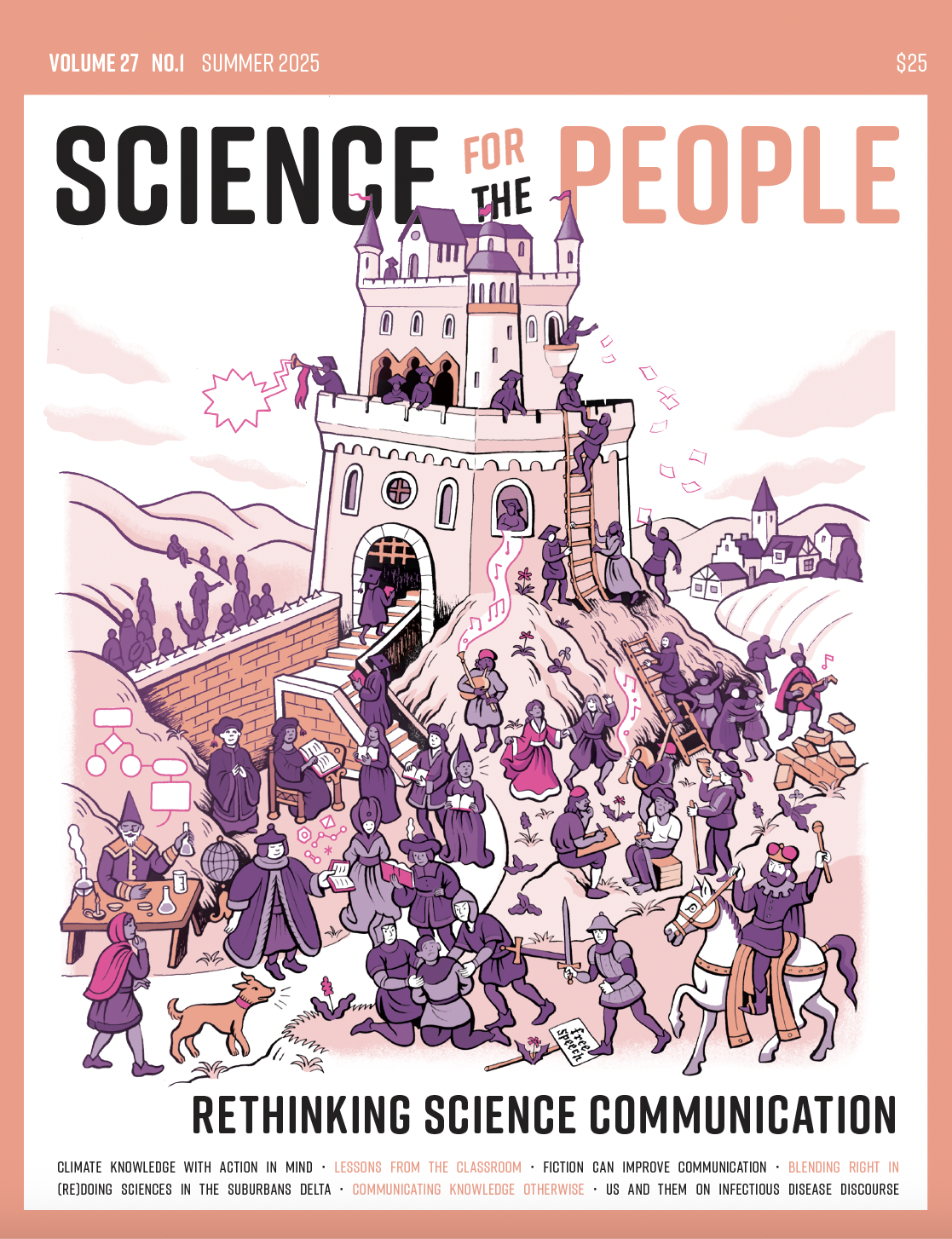

Certainly, there is much to learn from the lineage of participatory action research (PAR) and historical examples like the free community health clinics organized by the Black Panthers and the Young Lords. Yet there is also a danger of looping fundamentally different communicative practices and approaches into a single broad umbrella concept like “participation” or “dialogue,” as we run the risk of washing the status quo with a “radical” sheen. While moving beyond the deficit approach and calling for more participation and engagement, we should also be zoned in on more ambitious goals and outcomes. Are we still trying to increase the public’s knowledge of scientific concepts–albeit in a more nuanced way–or are we communicating to upend the way science is done? We do see value in devising new experiments in public engagement, in demystifying obscure but important concepts, and in translating science for different peoples and communities. We want to take the labs into the streets, to break down the walls between the classroom and the community square, and to fight the power imbalances that have historically led to divides between the priestly class of the scientifically literate and those kept outside the gates. But there are bigger changes that we need to face, which cannot be accomplished by adopting more inclusive approaches to the communication of bourgeois science. We must also share, aggregate, and act on knowledge globally, even as we seek to empower local communities. We must apply critical judgement to both the processes and results of scientific research, with an eye to whom they serve and the biases scientists might bring to their work, but avoid creating blanket distrust that is destructive to meaningful progress. We cannot pursue radical approaches to science communication without radical science.

—Volume 27, no. 1 editorial collective