Art±Bio Science Murals:

Communicating and Visualizing Science via Public Art

By Stephanie Dowdy-Nava + Saúl S. Nava, Ph.D.

Volume 27, no. 1, Rethinking Science Communication

“Pollination/Polinización” a Science Mural at the YWCA Shirley Leavell Branch by the Art±Bio Collaborative captures the remarkable moment when a White-lined Sphinx Moth (Hyles lineata) hovers in midair, its proboscis reaching into the luminous fiery bloom of a Long-spined Purple Prickly Pear Cactus (Opuntia macrocentra). By highlighting the critical role of pollination, the mural reminds us that every small act—be it by moth or human—can have a profound impact on the world. Learn more at sciencemurals.com

On the eastside of El Paso, Texas, situated within one of the most biodiverse deserts in the world, a six-foot White-lined Sphinx Moth slurps nectar from the bright yellow bloom of a Purple Prickly Pear Opuntia Cactus.1 The moth’s signature six-lined wings are outstretched—pink hindwings visible, proboscis unfurled—as it pollinates the fiery flower floating between dreamy layers of purple cactus pads. Along the horizon, magnified pollen grains from endemic plants dot a stylized mountain line. This is a “Science Mural,” and it features a larger-than-life depiction of pollination, the process of plant reproduction by which pollen is transferred between plants. As the moth sips nectar, its body picks up pollen grains, transferring them between flowers—which ensures the next generation of purple opuntias. In vivid detail, the Pollination/Polinización Science Mural greets Borderplex children and adult visitors outside of a community center at eye level and in two languages, in just one example of how the Art±Bio Collaborative communicates science and transforms unexpected public spaces into community classrooms, studios, and labs that engage bilingual neighborhoods in science learning.

As the cofounders of Art±Bio Collaborative, an artist and scientist-led organization that fosters the integration of art, science, and nature through novel collaborations, public engagement, education, and research, our work cultivates social dialogue and creative exchange of ideas with diverse publics.2 Via innovative Art+Science programming, we create meaningful opportunities for the leadership and participation of marginalized communities at a critical time, enhancing creativity through science learning and elevating science communication through visual art to challenge dominant institutionalized perspectives. Science Murals, our ongoing public art initiative, serves as a public visual dictionary of scientific terms, breaking down complex ideas and concepts into understandable and inviting images and demystifying scientific jargon.3 The murals inspire science-focused placemaking and provide transformative public engagement—activating artists to become science communicators, scientists to communicate artistically, and guiding viewers to learn about scientific concepts that can be obscure and inaccessible to many.

Science Muralism: Bridging Public Art and Science Engagement

Art can serve as a bridge between disciplines and to the public, making complex subject matter and ideas more inviting and relatable. While science-related misinformation/disinformation is intentionally spread online and federal funding for the arts and scientific, environmental, and medical research is cut by billions, Science Murals prioritize sharing knowledge.4 Access to natural resources and the discoveries, advancements, and creations of the arts and sciences are universal human rights.5 Inspired by this, we created Science Murals to cultivate a more holistic and culturally inclusive approach to science communication and foster a multidirectional exchange of knowledge through imagery and community collaboration.

In times of “information voids,” ensuring access to accurate scientific information that is of interest to people effectively counters mis/disinformation.6 Public art that informs, like mural paintings, the most ancient form of human visual art, can raise awareness and inspire social change—vital components to science communication. For example, modern muralism originated in Mexico in the early twentieth century as a tool for promoting cultural identity, education, and communicating technological advancements. Mexican Muralism actively mobilized communities to engage in scientific and environmental advocacy, fostering public discourse on the role of science in shaping Mexico’s future.7 Public murals are a powerful medium for communicating science because they engage diverse audiences of all backgrounds through the emotional appeal of a vibrant image, with minimal words and maximum accessibility.8 Accordingly, public murals that depict biological/scientific imagery and concepts can be creative catalysts for science engagement, environmental education and stewardship, and community outreach and empowerment. We call this Science Muralism.

When art poetically imbues biological concepts with symbolism and metaphors, transforming it into vibrant, educationally enriching, and culturally relevant imagery as Science Murals do, it can elicit emotional connections that have lasting impacts for both viewers and artists. We term this “biopoetics” and “biosymbolism.” El Paso artist Leslie Alcala explains, “Art can make science approachable and memorable, while science can provide new ideas and perspectives to explore for art, leading to more powerful storytelling.” As such, Science Murals communicate messages through layered visual narratives, resulting in rich science learning experiences that cultivate joy, ignite curiosity, and elicit empathy for the environment.

Science Murals—Placemaking for Spatial Justice

To date, we have created twenty-one Science Murals in two major geographic regions, with contributions from over forty artists and eleven scientists, with plans to install more murals including Medical Murals and Math Murals. Because Science Murals create spaces for science engagement, in and of themselves, their placement must be strategic and equitable, to position educational resources in under-resourced areas.

In New England

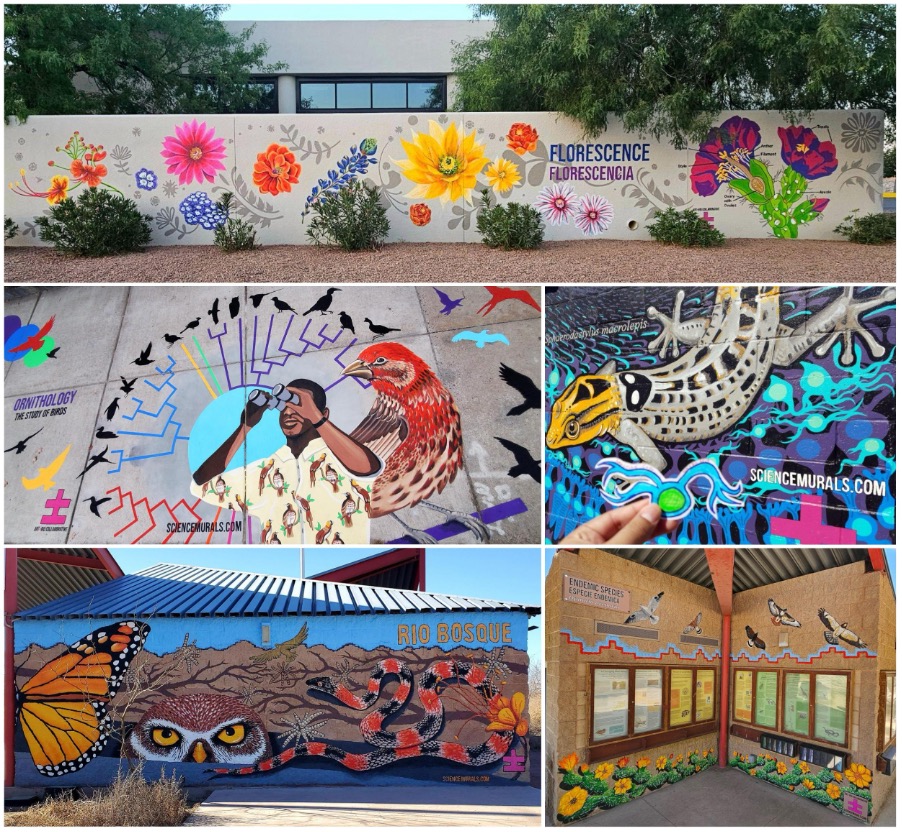

We first launched Science Murals in 2016 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, our home base, to highlight the discoveries of scientists of color happening in local research labs, including Harvard and MIT. Despite being situated within Cambridge, these institutions remain largely inaccessible to the marginalized communities neighboring them. In response, we create Science Murals and develop experiential learning programs for youth in Cambridge neighborhoods like The Port, with the densest population of Black, Brown, and immigrant residents and the fewest economic resources. Science Murals and outreach here focus on the visual systems of Diurnal/Nocturnal Caribbean geckos. They showcase Ornithology, represented by a Black birder, a phylogenetic tree, and dozens of bird species. Art±Bio’s first Math Mural, Absolute Value, is based on the lives and activism of civil rights icons, Algebra Project founders, and Port residents, doctors Bob Moses (1935–2021) and Janet Moses—created collaboratively at The Port’s Moses Youth Center with teenage participants from Art±Bio’s impactful Youth Science Mural Program.9

En La Frontera

The first public Science Mural in El Paso, Texas, our hometown and sister city to Las Cruces, New Mexico and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, was painted in 2022 at the Rio Bosque Wetlands Park, a nature preserve situated alongside the border wall, as part of our inaugural Sun City Art+Science Festival. The large-scale Science Murals Initiative followed in 2023, with seven Science Murals created collaboratively with local established artists and community partners, highlighting scientific areas of study.10 In 2024, we designed and installed six Science Murals focused on regional plants and pollinators with four mentors and five art+design college students/recent graduates from regional universities—mentees in an inaugural “Science Mural Mentorship” program designed to build community and cultivate the next generation of Science Muralists.11

We strategically brought Science Murals to El Paso to prioritize ArtScience engagement in Latino communities. This region forms one of the largest binational metropolitan areas and busiest border crossings. El Paso County’s growing population is over 83 percent Latino, roughly 65 percent speak Spanish, and almost 22 percent are immigrants from Latin America.12 Science Murals are our love letter to El Paso. They are inspired by the local landscape, celebrating the culture, ecology, and unique biodiversity of the Chihuahuan Desert, which extends from Northern Mexico into the Southwest U.S.—a geographic expanse that brings to light the arbitrary nature of imposed borders on ecological habitats and community identities. Both the harmful effects of climate change in the Chihuahuan Desert and the regional wildlife celebrated in our Science Murals, transcend borders, as communities on both sides share an identity with the natural environment and ecology. Science Murals here promote conversations about science, identity, conservation, nature, and their relevance to everyday life within the community. The concepts they illustrate and stories they tell are infused with biopoetics and biosymbolism directly related to the culture and ecology of the desert.

By focusing on wildlife of the contested region of the borderlands, Science Murals invite personal connections with La Frontera’s inhabitants. They foster pride in and promote caring for regional biodiversity and build trust in science by uplifting, representing, and validating viewers’ personal experiences with the environment.13 We returned to the Rio Bosque for El Paso’s sixteenth Science Mural, to depict a sprawling endemic cactus and several raptors as a means to identify keystone species growing underfoot on either side of the border wall and soaring overhead in skies that span two countries—demonstrating that walls aren’t simply barriers; mural walls can be windows to knowledge and portals into a community’s heart.

The Bosque is home to three Science Murals highlighting endemic species and vital desert organisms. Endemic species are found only in a specific geographic region, making them more vulnerable to extinction due to their limited distribution. Our ambition is that murals featuring iconic wildlife will spark environmental advocacy and inspire tangible conservation actions, such as with activism and policy initiatives protecting marine ecosystems.14 El Paso artist Esmirna Cordero acknowledges that depicting local biodiversity in public art “not only educates, but also deepens appreciation for the natural world, encouraging people to take an active role in conservation.” By spotlighting vulnerable species and embedding them within neighborhoods, Science Murals become part of the community, potentially creating lifelong relationships between residents, art, science, and appreciation for the living environment.

Science Murals include mentorship programs, community activations, and public celebrations animated with all-ages biological artmaking and festive Mariachi performances.

Science Murals as Transformative Public Engagement

Beyond the high-impact visual imagery, Science Murals are enriched with scientific terms in English and Spanish and bilingual community activations. Art±Bio science communicators engage audiences with Art+Science outreach that address issues concerning El Pasoans, like climate change, environmental education, and quality of life.15 These include lesson plans reinforcing the murals’ content and environmental education, online public drawing sessions about desert ecology and biodiversity loss, school visits led by scientists and artists, and mural celebrations animated with artmaking and soulful Mariachi performances. El Paso YWCA CEO Sereka Barlow states, “These artworks do more than beautify our spaces; they enhance learning while ensuring families who may not have had regular access to art or science can experience it. We’re excited to use these murals as community classrooms, enriching our Academies for Early Learning with creativity and knowledge.”

Interacting with Science Murals encourages viewers to engage in scientific and artistic pursuits on their own, resulting in multigenerational community empowerment. One elderly man witnessing Science Mural installations enrolled in community art classes, explaining he was inspired by the artists painting in his neighborhood. After chatting with the artists about the meaning of the term Especie Endemica, another Spanish-speaking adult mother-daughter pair excitedly shared their intention to research which endemic species they might spot and protect in their neighborhood, appreciating that the mural featured terms en Español. Artist Alexandra Urbina recalls growing up in El Paso, accustomed to the murals sprinkled throughout the city, but unaware of their potential to be educational tools until participating in the Mentorship program: “What I most admired about the murals we painted was how they focused on native flora, fauna, and culture. By combining the iconography—such as the cacti and floral designs on the Florescencia Mural—and text in both English and Spanish, our murals become interesting to the local Latino public. They see the beautiful imagery in their neighborhood, read ‘Endemic Species/Especie Endemica,’ and wonder what that means and how it relates to the plants they see.”

Furthermore, our public engagement efforts extend to our artist and scientist collaborators. Enlisting emerging artists and regional scientists constitutes vital community participation, representing our most important level of outreach. When artists engage the public, they amplify the voices, concerns, identities, and imaginations of entire communities. The artists who create Science Murals are themselves members of the local community. Like the greater public, they typically are not institutionally trained in, nor formally associated with, academic science. Through the mentoring, research, and learning required to make Science Murals, artists become both recipients of science engagement and disseminators of science—thus deconstructing institutionalized ideas that only “traditional scientists” can communicate science. The Mentorship team paints side-by-side, discussing science and nature, sharing mural-making techniques, and developing and leading ArtScience activities for adults and school groups. Through this process, student-artists become experts on mural topics and effective science communicators.16 They input their own creativity into the making of Science Murals and the imagining of future murals, and they continue to take inspiration from the environment and teach science through their art after the program. We term this journey, in which students learn then take on leadership roles in teaching others, “multilayered learning.”17 Esmirna Cordero affirms, “The Mentorship program has significantly influenced my art and deepened my appreciation for the natural beauty of my city. Collaborating with mentors, scientists, and artists has reinforced my belief that art is a powerful tool for teaching and learning.”

Participating scientists likewise gain creative communication skills and greater artistic and visual literacy. In 2023, Gabriela Franco, Biologist and Program Leader at Asombro Institute for Science Education, personally worked with muralists, “to intentionally design the murals to include local research, plants, and animals so we can communicate the amazing science of the area to both school groups and the public.” Asombro’s Chihuahuan Desert Nature Park is home to the Desert Ecology/Ecología del Desierto Science Murals—two large-scale teaching tools viewed in-person by more than 1,200 students annually. Every guided nature hike at the park begins by exploring these artworks with a scientist. In extending focused mentorship and artist-scientist collaborations, Art±Bio Collaborative is ensuring Science Muralism takes root—leading to transformative science engagement, environmental education, and continued science learning in the communities that engage with the art.

Concluding Observations

Creating, experiencing, and learning from Art±Bio Science Murals inherently connects and expands viewers’ and artists’ relationships with the local ecology and the life sciences, and positively inspires and invites the publics’ reimagining of who can experience and participate in Science and Art. The experiences of marginalized populations are rarely represented in traditional science narratives—or acknowledged within science classrooms.18 Las Cruces-based artist Citlali Delgado was moved by a 2024 presentation by Indigenous scientist and author Dr. Jessica Hernandez, who explained that science comes in many forms—including those of our ancestors who were experts in the land since the beginning of their existence.19 Delgado reflected, “to think that one must be an institutionally educated person of science to have the label of ‘scientist’ participates in an eco-colonialist mindset that has been historically against indigeneity.” She concluded that collaborative artmaking can diminish the intimidating stereotypes of science, adding: “Through imagery like Science Murals, we will continue to reinforce that sense of knowledge as if our audience were plants, and these murals were pollinators.”

At the time of publication, science, education, and the arts are being discredited, censored, dismantled, and defunded while scientists, educators, people of color, immigrants, and conservation efforts are maligned. While widespread mis/disinformation deliberately sows distrust in the scientific enterprise from the general public, the radical and vital act of collaboratively making public art and communicating science—in marginalized communities, en La Frontera, and beyond—is more critically necessary, than ever before.20 Science Murals, rooted in the earliest and most enduring form of human artistic expression and inspired by the cultural urgency and global legacy of Mexican Muralism, may indeed be the most direct and expressive way to communicate science and inspire public participation and discourse. With confidence, Science Murals will live on in the hearts, minds, and walls of the communities with which they are indelibly intertwined—a step towards empowering communities to weather the storms that lie ahead.

—

Art±Bio Collaborative is a mission-driven organization cofounded and led by Stephanie Dowdy-Nava, MA and Saúl S. Nava, PhD, two native El Pasoans who have launched an unprecedented Science Murals Initiative in the region, with the goal of communicating science and making El Paso, TX the Science Mural Capital.

Dr. Saúl S. Nava is a Professor of Biology and Life Sciences and Founding Chair of the new Department of Integrative Sciences and Biological Arts at Massachusetts College of Art and Design. He develops and teaches courses on BioAesthetics, Visual Ecology, Desert Ecology, BioPoetics, Animal Communication, Science Engagement, and many other courses and Field Studies that integrate Art, Science, and Nature. He is the co-founder of Art±Bio Collaborative and an active artist and science muralist.

Stephanie Dowdy-Nava, MA, is an artist, arts administrator, educator, science muralist, and co-founder of Art±Bio Collaborative and the Science Murals Initiative. She directs Field Studies of Art+Nature, teaches Art/Art Education at JK—College levels, and leads Art+Science outreach and public engagements in schools, universities, nonprofits, museums, and international settings. She is dedicated to creating accessible educational opportunities that engage diverse communities, promote curiosity, and creatively explore the intersections of science learning and artmaking.

More articles in Rethinking Science Communication will be posted over the next month. Subscribe/purchase this issue to read it today.

Notes

- “Chihuahuan Desert,” World Atlas, accessed May 15, 2025.

- “About,” Art±Bio Collaborative 2025.

- “Science Murals,” Art±Bio Collaborative 2025.

- Derek Robertson, “The Mystery of Trump’s Science Cuts,” Politico, May 22, 2025.

- UN General Assembly, Resolution 217 A, Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), Article 27 (December 10, 1948).

- Ayla Fudala, “Understanding and Addressing Misinformation About Science,” Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, January 23, 2025.

- Gustavo Corral Guillé, “Ciencia y tecnología en los murales de la Ciudad de México (1933-1952) [Science And Technology In The Murals Of Mexico City (1933-1952)],” Andamios 21, núm. 54 (May 2024): 303-332, https://doi.org/10.29092/uacm.v21i54.1072.

- Blake Thompson et al., “Street Art as a Vehicle For Environmental Science Communication,” Journal of Science Communication 22, no. 4 (June 2023), https://doi.org/10.22323/2.22040201.

- “Who We Are,” The Algebra Project, accessed April 15, 2025.

- This project was supported by the Simons Foundation’s Science, Society & Culture division. “Science, Society & Culture,”Simons Foundation, accessed July 14, 2025.

- “Science Mural Mentorship,” Art±Bio Collaborative 2025, https://www.artbiocollaborative.com/sciencemuralmentorship.

- “El Paso Texas, County,” United States Census Bureau, accessed April 15, 2025; “El Paso, TX Metro Area,” Census Reporter, accessed April 15, 2025.

- Cynthia L Bejarano and Jeffrey P Shepherd, “Reflections from the U.S.–Mexico borderlands on a ‘border-Rooted’ paradigm in higher education,” Ethnicities 18, no. 2 (April 2018): 277–294, https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796817752559.

- Stefania Benettia and Giovanni Modaffari, “Environmental Awareness Through Mural art: a Survey of Iconographic Representations of Whales and Polar Bears on Italian Walls,” Journal Of Research And Didactics in Geography 2, no. 13 (December 2024): 113-130.

- “El Paso Regional Climate Action Plan,” City of El Paso, Office of Climate & Sustainability, March 2024, 5.

- Patricia Rios and Aquiles Negrete, “The Object of Art in Science: Science communication via Art Installation,” Journal of Science Communication 12, no. 3 (December 2013). https://doi.org/10.22323/2.12030204.

- Alison Dell et al., “Shadow Ecologies: Shadow Puppets as Science Performance,” Identity, Culture, and the Science Performance Volume 1. From the Lab to the Streets, ed. Vivian Appler and Meredith Conti (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2023), 81-83.

- Daniel A. Colón-Ramos, “The Need to Connect: On the Cell Biology of Synapses, Behaviors, and Networks in Science,” Molecular Biology of the Cell 27, no. 21 (2016): 3203–7, molbiolcell.org/doi/10.1091/mbc.E16-07-0507.

- Jessica Hernandez. Fresh Banana Leaves: Healing Indigenous Landscapes through Indigenous Science (North Atlantic Books, 2022).

- Shanto Iyengar and Douglas S. Massey, “Scientific Communication in a Post-truth Society,” PNAS, November 26, 2018, doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1805868115.