Rereading China: Science Walks on Two Legs in 2021

Reflections on the 1973 Trip

By Vinton Thompson

It is not every day that one has the opportunity to reflect almost fifty years down the road on a life-changing set of experiences. We were young. I was twenty-five. Only two of us were over thirty. It was February 1973 and we were immersed in the struggles of the times. The Vietnam War, which had expanded into all of Indochina, was raging, its denouement still two years in the future. Nixon, reelected in a landslide in November 1972, had launched a massive Christmas bombing raid against Hanoi two months before we arrived in China. In a year and a half he would be driven from office. When our little delegation of ten set out from San Francisco to Guangzhou via Honolulu, Japan, and Hong Kong, the times were still very much a-changin’.

There was lingering uncertainty about the nature of our visit when we arrived in Guangzhou. It had not been settled with certainty, for example, who would pay our costs in China, we or our hosts? The whole issue of who our hosts were was also up in the air. We had anticipated being guests of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Evidently, when our motley crew of young activists arrived, not an established scientist among us, there were second thoughts and our official host organization became the Chinese Association of Science and Technology. It was a better fit, and they did, much to our relief, agree to cover our in-country expenses.

It would be impossible to overstate our excitement on walking into China across a small wooden bridge as we changed from the Hong Kong train to the People’s Republic railway system at Shumchun, now Shenzhen, a place unimaginably transformed since our passage through on February 21, 1973, when you could still see farm animals from the railway station. We were entering a China that had been forbidden to all but a select few Americans until two years before. (Before departing, I had asked the Chicago Passport Office what to do about the clause in my passport that forbade travel to communist-controlled parts of China. They crossed it out with a magic marker.) China supported our allies in the Vietnamese liberation struggle. They were resolutely free and independent of the reigning superpowers. They seemed to be creating a radically egalitarian society that aligned with our 1960s movement values—equality for women and ethnic minorities, fair distribution of wealth, and empowerment of ordinary workers. We could not have been happier or felt more special to be there.

The China we visited bore no resemblance to the urban China we see today. It was poor, undeveloped, and culturally isolated. Our hotel in subtropical Guangzhou had mosquito nets—no air conditioning in sight. Beijing was still full of horse and donkey carts. There was a spartan austerity, reflected in simple clothing and hairstyles, but the people were not impoverished in a conventional sense—no rags, no beggars, and no malnourished children. We encountered a country convinced it was poised for development—and we shared that view—but when development came, it took an entirely different path than what we or our hosts envisioned in 1973.

I returned to China in 1979, 2002, and 2013. I doubt a more astonishing social and economic transformation has occurred anywhere on Earth in such a short time frame. That story has been told elsewhere many times. We and other foreigners who caught a snapshot of China towards the end of the Cultural Revolution had a unique experience. The seeds for the transformation of the 1980s onward were sown in fits and starts in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. We were there to bear witness, however imperfectly, to a portion of the social ferment that gave rise to these changes.

We encountered a country convinced it was poised for development—and we shared that view—but when development came, it took an entirely different path than what we or our hosts envisioned in 1973.

As they figured out who we were, our Chinese hosts were eager to show off their society. They loved our name and slogan “Science for the People.” What we lacked in professional heft, we made up for in sincerity and enthusiasm. On our late-night arrival in Beijing, one of our young interpreters made a joking reference to Frank Mirer’s first name. He said it fit because Americans are frank, and noted that Ernest is also a good American name. Earnest we were, in spades. At the beginning, to combat hierarchy, we designated a new group leader every day. Our hosts put their foot down—we had to designate one leader. We chose Geri Steiner, who now goes by Elisabet Sahtouris, one of our two adults.

Our transparent commitment to the Chinese cause opened many doors, a few so wide as to be uncomfortable. At one point we were ushered into an operating room while a patient was undergoing brain surgery. In Shanghai, we had the extraordinary opportunity to visit the Municipal Prison, said to be the only jail in the city. We walked among the prisoners, many of whom were wielding small knives to carve the rough edges off plastic injection moldings. Could we really have understood in any useful way what was going on there? We asked and were told that the prisoners could participate in “criticism, but not slander.” They did not speak in our presence and, with the exception of one small parenthetical reference and inclusion in the itinerary listings, that excursion did not make the book.

What did we take from our experiences in China? My strongest, most enduring impression was how self-contained, self-sufficient, and self-reliant Chinese people were. They were immensely proud, with good reason, of how completely they had seized their own destiny, throwing off their historical subordination to outside powers. From an American perspective, it was profoundly moving to see a whole working society run from top to bottom without a person of white European descent in sight. Similarly, when George Clements, a progressive Chicago African-American Catholic priest, returned from a visit later in the 1970s, he told me that the lesson he took from China was that the oppressed can organize and run things themselves, without paternalistic help.

We were all white. While there are people of multiple ethnicities in China, including people of “Caucasian” origin, the vast majority everywhere we went were East Asian. We had the experience, rare for white Americans, of being a conspicuous racial minority. Outside Shanghai, even in the large cities of Beijing and Guangzhou, people, especially children, gawked at us openly. We could not shop or walk down the street without attracting a crowd of onlookers. Another feature caught the attention of our hosts—four out of ten of us were left-handed: me, John Dove, Frank, and Geri. We were lefties in more than the political sense. Among hundreds of Chinese people I encountered in circumstances that revealed handedness, I saw exactly one southpaw—how I wished I could have communicated with him directly. This was just one instance in which Chinese society seemed to be profoundly repressive. For another, as good “movement people” (i.e., activists), we did ask about gay people in China. We were told that if their orientation interfered with sleep, they were given pills—a clear indication that gay liberation was not on the state’s agenda.

I came away from China energized to help the Chinese people build their society as we struggled to transform ours. On the advice of Ann Tompkins, a resident American “friend of China,” I sought out George Lee, who was putting together an active chapter of the US China Peoples Friendship Association (USCPFA) in Chicago. I was surprised he was Chinese-American—in my provincial American way I had been thinking of Lee as in Robert E. Along with many other local activists we worked hard to promote the USCPFA and widen direct people-to-people cultural contacts. Eventually, I served for a period as chair of the local chapter. George, who grew up in the back of a Chinese laundry in New Jersey, died of AIDS in the early 1980s, before researchers found effective treatments.

They loved our name and slogan “Science for the People.” What we lacked in professional heft, we made up for in sincerity and enthusiasm.

After the trip, I spoke as widely as I could on our China experience. There was tremendous curiosity about China, and it was easy to find small gigs. In all, I did about fifty engagements, from tiny to large, usually embellished with slides of our visit. The modest proceeds went back to support the publication of the book. I think we were effective in countering several decades of demonization of the People’s Republic of China. We had the advantage of going with the flow of history. Following the Nixon-Kissinger visits shortly before our trip, the US and Chinese governments carried out a policy of rapprochement. No doubt our activities served their purposes, but in the context of America in the 1970s, simply speaking positively of a socialist society and demonstrating to Americans that oppressed people can seize their own destiny had a subversive aspect. This was not lost on the authorities. A highly redacted FBI file has a vignette of our delegation at the Japan Airlines counter at San Francisco Airport. The agents noted our SftP buttons and stated that we “were dressed in an array of dungarees, sweaters, odd trousers and shirts … knapsacks and shoulder bags.”1 I distinctly recall a stranger snapping photos of us as we boarded.

The trip also reinforced our commitment to work in solidarity with Vietnam. I usually characterize SftP as an antiwar group. The Vietnam War brought us into existence and sustained our activism through the mid-1970s. We had disparate political views, all progressive, mainly left, but scattershot beyond that. Opposition to the war and its consequences united SftP and our delegation. This was especially true for Mary Altendorf and me. Our local (Chicago and Minneapolis) SftP chapters were centered on the Science for Vietnam project, an attempt to provide concrete scientific support for the people of Vietnam in their struggle for independence.

Not surprisingly then, the delegation made a beeline for the Vietnamese embassies in Beijing. There were two, one for the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (the DRV, North Vietnam) and one for the Provisional Revolutionary Government of South Vietnam (the PRG, the insurgents in the South). The embassy visits were strikingly different. The PRG occupied a modern, sunny low-rise building. We visited during the day. The staff were friendly, warm, and welcoming. They laughed and treated us as brothers and comrades (they were all men). The DRV occupied an older, staid building in the traditional embassy section. We visited at night. They were stiff and formal. After ushering us in and going through a few formalities they sat us down for films of the American bombing of Hanoi the previous December. I wonder to this day what became of those PRG patriots after the abrupt reunification at the end of the war.

We flew home across the Pacific on Japan Airlines, surprised to find that we had all been bumped to first class. To this day it is the most luxurious flight I have ever taken. Why the good luck? A glimpse into coach revealed that everyone was Japanese, and they had all, men and women both, stripped to their underwear for the long flight. They had segregated the Westerners in luxury. All the best for me. I had developed a bad cold in China that had morphed into severe bronchitis. It took weeks at home to fully recover.

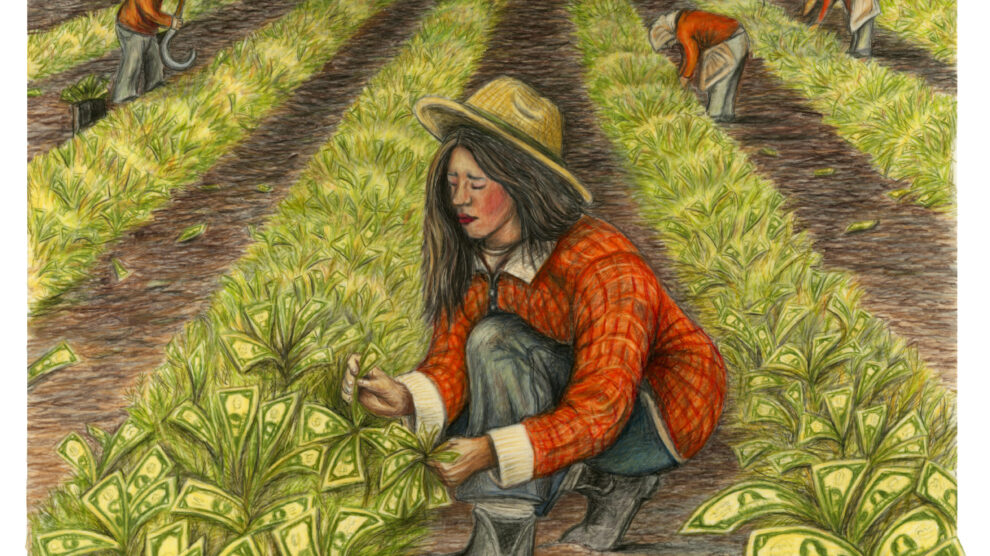

A word on the book as it is reissued online: it was the most visible product of the visit and probably the most enduring, our stab at mass popular outreach. It was integral to the project from the beginning. We had many group meetings devoted solely to its development, starting in San Francisco before the trip. We divided notetaking systematically and recorded sessions on cassette tapes to ensure accurate records of what we saw and were told. In the spirit of the times, the book was a collective enterprise, with no attribution of individual authorship. My contributions comprised about a fifth of the total, including Chapter 2 on agriculture and the parts of Chapter 4 on the zoology, genetics, and entomology research institutes. The book presents, as best we were able, Chinese society as our hosts wanted us to understand it at that time and in that place.

Back to Table of Contents

Notes

- The FBI files on SftP, along with other primary-source materials on the history of the organization, are available at http://science-for-the-people.org. The two files specific to the 1973 China trip are 100-459865-86 (which includes the material referenced here) and 100-459865-88.