Communicating Knowledge Otherwise:

Reclaiming Latin American Participatory Action Research to a Global Citizen Assembly

By Iñaki Goñi

Volume 27, no. 1, Rethinking Science Communication

What is our obsession with reports? As I work on the data strategy for a permanent Global Citizens Assembly, where citizens worldwide deliberate on global issues and plan for local action, most of our discussions about communicating results revolve around reports.1 Indeed, the go-to formats for translating research into political action often center around policy memos, academic publications, or short presentations to decision-makers, which prioritize formal language and institutional traceability. But the more I engage with my work, the more I wonder: Do these reports mobilize local political action and deepen participation or serve bureaucratic needs?

As a scholar from Latin America, I know there are empowering ways to communicate research just by looking at the rich participatory traditions of the Global South. In particular, Latin American Participatory Action Research (PAR) can help reimagine modern research communication in the context of large-scale participation in science and technology.

PAR emerged in the 1960s and 1970s to challenge the top-down nature of research.2 Instead of treating communities as research subjects, it promoted a diálogo de saberes (dialogue of knowledges) where local, Indigenous, and everyday expertise were seen as equals to academic expertise.3 The essence of PAR is perhaps best encapsulated by Paulo Freire’s concept of “praxis,” outlined in Pedagogy of the Oppressed as the interplay of reflection and action to foster conscientização (critical consciousness), which helps communities build social awareness and drive collective change.4

What one must understand from PAR is that, for its practitioners, participation and communication are a human right and fundamental need. As Paraguayan communicator Juan Diaz Bordenave phrased it, “Communication and participation should be perceived not as methodological options . . . but as organic parts of a much larger and important process: the historical collective construction of a participatory society.”5 In this context, participation and communication are “a philosophy of life, an experiential attitude that saturates all the important aspects of personality and culture. It gives meaning to existence and, therefore, tends to produce or condition all the structures of society.”6

Naturally, the context in which they developed these practices differs from today’s. Thus, what we can learn from these sometimes forgotten practices is still an open question, one I would like to consider in my work supporting the Coalition for a Permanent Global Citizens Assembly.

As I uncover these histories, I am compelled to share two significant examples that hold valuable lessons for today: the work of Orlando Fals Borda and Ulianov Chalarka in Colombia and the efforts of Francisco Vío Grossi and Oscar Nuñez with the nongovernmental organization (NGO) Canelo de Nos in Chile. I strongly believe their works present a powerful alternative to the hierarchical and extractive models of conventional research communication that we find reflected in technical reports, policy memos, or academic articles.

Participatory Comic Books: Systematic Devolution with Orlando Fals Borda and Ulianov Chalarka

In the early 1970s, Colombian sociologist Orlando Fals Borda and his team the Caribbean Foundation (Fundación) spearheaded an innovative research approach that bridged academic inquiry with grassroots activism. Working with the National Association of Peasant Users (ANUC), an agrarian movement advocating for land rights through direct action, land occupation, and mass mobilization, Fals Borda concentrated his efforts on the coastal department of Córdoba. There, he established a local research collective, La Rosca, or the Spiral, that not only reclaimed knowledge from the struggles and histories but also generated an archive for research to support active political organizing.7

Amid the struggle between large landowners and peasants over land reform, La Rosca created manuals for peasant self-organization workshops (cursillos) based on historical research and documented contemporary political protests, such as the Great Peasant Demonstration of 1972 led by female banana workers.

Their historical research was driven by the desire to mobilize political action in the present, specifically around land reform, and the rights of women and the working poor. Fals Borda’s team documented oral political cases along the Caribbean coast, where landless peasants escaped debt peonage by forming self-organized bastions (baluarte). ANUC later used this research to frame their Hacienda occupations as “new bastions of peasant self-determination.”8

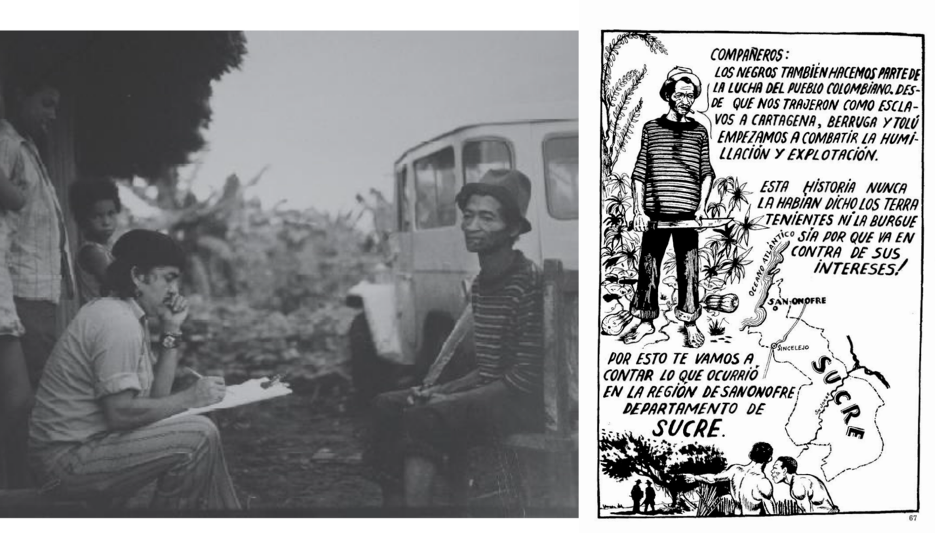

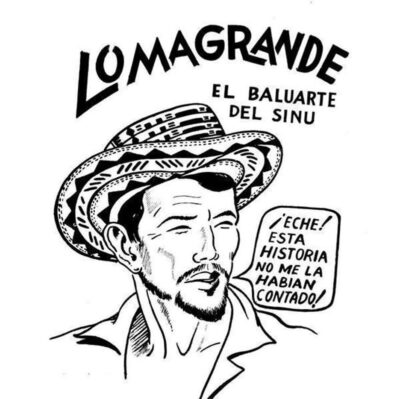

A defining element of this work was the use of creative media to expand participatory research. Between 1972 and 1974, Fals Borda and the Fundación produced four graphic narratives recounting peasant struggles in the Córdoba and Sucre regions. These comics—Lomagrande (1972), El Boche (1973), Tinajones (1973), and Felicita Campos (1974)—were products of meticulous participatory research and were illustrated by Ulianov Chalarka, a working-class artist from Montería. Known for his caricatures and religious portraits, Chalarka brought the stories to life with visuals that resonated deeply with the local communities. Each comic, spanning fifteen to twenty pages and taking six months to create, recreates the oral tradition among peasant communities in narratives of resilience and resistance as told by a current or past community leader.

These comics critically recovered knowledge of historical struggles for land and their connection to current political conflicts. Lomagrande explores land appropriation from the Spanish conquest to Córdoba’s landowners, tracing agrarian associations from the late nineteenth century to the 1970s. Tinajones follows peasant communities near Boca de Tinajones, which reclaimed uncultivated land in the 1920s, only for landowners to later claim it without ever working it. El Boche follows a day laborer who leads a peasant uprising on the Misiguay estate near Montería. Fals Borda’s team reinterpreted his story, once framed as criminal, through the peasants’ struggle against unfair conditions and Hacienda authority. Finally, Felicita Campos depicts a peasant woman’s fight for land rights in 1970s Sucre. Portrayed as protagonists, women along with peasant and worker associations challenged the dominant patriarchal culture amid Colombia’s social and political upheaval.

Orlando Fals Borda’s methodology blended historical research, creative storytelling, and grassroots engagement. The process began with the formation of working groups including peasant activists from the ANUC, community members, and researchers from the Fundación. These groups operated as the governance boards of the whole process.

Fundación researchers, including figures like David Sánchez Juliao, collected short stories about the everyday lives, political struggles, and oral histories of the communities—weaving these narratives with local political traditions and generational memories. Researchers, alongside communities, also conducted rigorous historical and contextual research in a practice that Fals Borda referred to as “critical recovery.”9 After gathering materials, the group reviewed findings and co-drafted storylines, which Ulianov Chalarka transformed into vivid comics that became engagement tools during participatory sessions and cursillos to spark reflection and discussion—what Fals Borda called “systematic devolution.”10

Importantly, Fals Borda and his colleagues used systematic devolution to support peasants in their fight for land. They revived political concepts like the bastions of peasant self-governance, detailed the history of land oppression that ignited debates, and also valorized the contributions of living peasant leaders as protagonists of the tales. For example, local organiser Ignacio Silgado (El Mello) narrated Felicita Campos, reminding peasants of women’s role in the land struggle. Thanks to the Colombian Banco de la República, we can all explore the comics on this website.11

What I take away: A more profound use of the arts goes beyond just using a creative medium. It should involve participation from the very inception and use the arts to trigger more participation and dialogue. The content itself should focus on the local perspective, telling the local history in the voices of the local heroes and leveraging this history to reimagine current political activism.

Systematizing Local Knowledge with Francisco Vío Grossi and Oscar Nuñez from Canelo de Nos

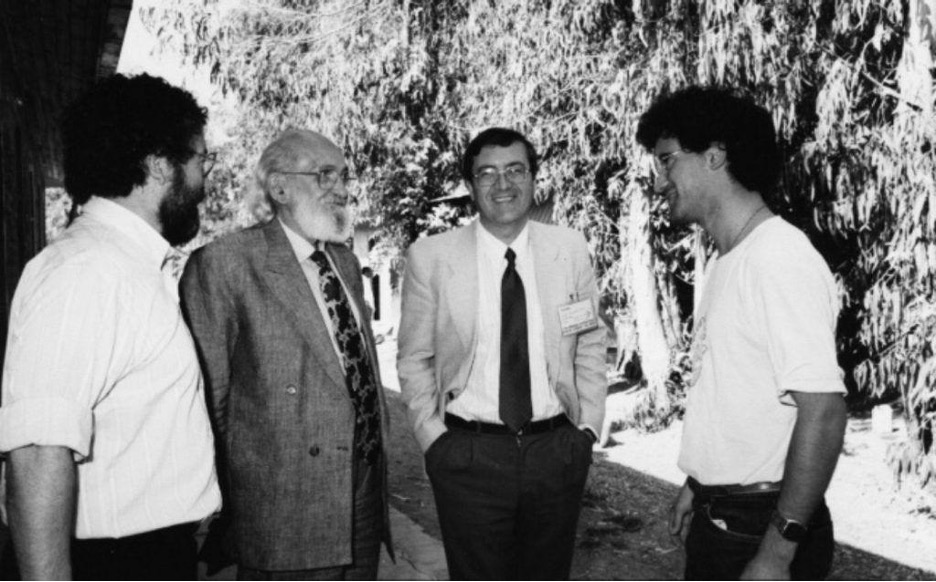

The story of El Canelo begins in 1985, nestled within the context of Latin America’s growing movements for adult education and grassroots development amid the political dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet in Chile.12Indeed, by the time Vío Grossi began leading the Council of Adult Education of Latin America (CEAAL), he had met Paulo Freire (who recorded one of his most significant interviews with Francisco in El Canelo).

El Canelo started as an experiment and evolved into a powerful symbol of self-sufficiency and local empowerment. Situated on 6.5 hectares in the sector of Nos, the center was divided into two main areas, each showcasing different models of self-sufficiency—from vegetable gardens and animal husbandry to pisciculture, fruit orchards, and the cultivation of native species. The modest yet expansive space had room for classrooms and ample gathering spaces, but more importantly, it served as a meeting point for all those interested in improving their livelihoods through local resources, sparking collective reflection and PAR.

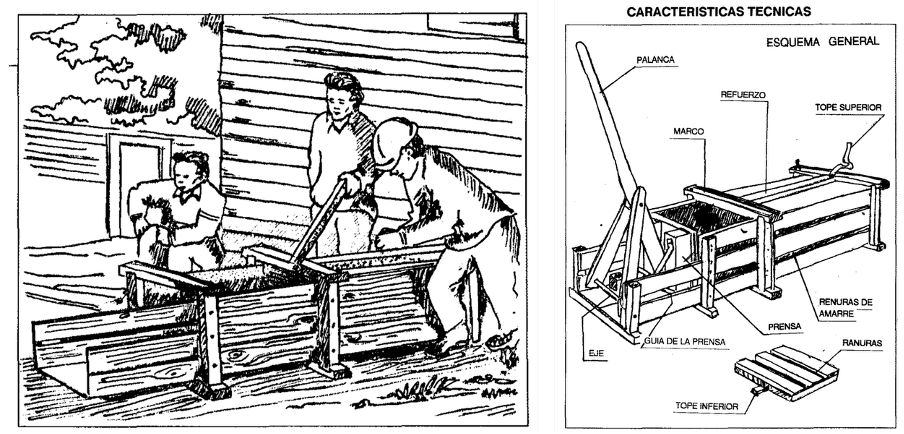

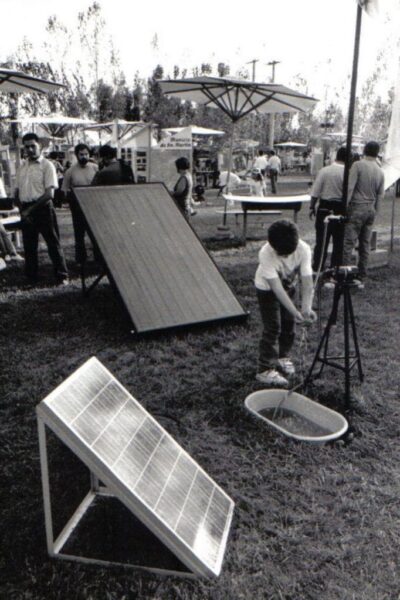

Among its first projects was the PAR initiative “Peasant Technologies and Organizations,” where they collaborated with local communities to systematize, document, and disseminate “peasant technologies” or bottom-up inventions in response to the common challenges faced by different communities.13 These technologies, such as solar cooking devices and adobe construction techniques, were not only practical but environmentally sustainable, providing an alternative to the resource draining practices often associated with rural life.

El Canelo’s methodology involved closely collaborating with local communities to document their different inventions, each meticulously recorded and analyzed, and conducting field research and interviews with community members to understand the context of these innovations. The Canelo de Nos team then worked with engineers to create technical drawings, enhancing the practicality and wider application of the inventions. This project led to initiatives such as the “International Fair of Popular Creativity, Alternative Technologies and the Environment,” where members from all communities could observe demonstrations of peasant technologies and also take pride in their innovations.

These innovations were also actively shared with neighboring communities through inter-community workshops and live demonstrations, enhancing inter-community solidarity. For this, the team leveraged the power of the arts to translate science and technology. For example, they produced short films where peasants could share knowledge through accessible formats, like film Por el pan nuestro (1984), directed by Hermann Mondaca and Ximena Arrieta.

Indeed, science, technology, and communications were always at the core of the work by El Canelo de Nos. Through its communications program, El Canelo launched its widely recognized magazine, El Canelo, as well as a community radio station, Radio Canelo, broadcasting on the 1490 AM frequency. Vío Grossi served as the director of the radio station, and the experience was transformative as it gave voice to the marginalized, brought forth crucial local debates, and educated audiences through entertainment, news, and cultural programming.

The cultural impact of El Canelo during the 1980s and 1990s was significant as the center became an essential space for the country’s cultural movements. The theater school at El Canelo served as a starting point for artists such as the renowned Chilean actress Tamara Acosta. El Canelo also gave birth to Circo del Mundo, a 1995 initiative in partnership with Cirque du Soleil and the Canadian organization Jeunesse du Monde, which worked with street children, using circus arts as a tool for human development and creative expression.

What I take away: A more profound systematization of knowledge should highlight the creativity and agency of the people. It should celebrate bottom-up innovation and help people demonstrate its value in practice. It should make people feel proud. We should literally throw a party (or organize a fair). Also, the communication of research should concern itself with the infrastructure. In whose infrastructure should we meet? In whose radio or schools?

Reclaiming Forgotten Lessons from the Global South

The Iswe Foundation is convening a coalition to institute a permanent Global Citizens Assembly. Central to our strategy is establishing both a “core” citizen assembly with citizens from all over the world and community assemblies in which everyone can organize their own deliberation and feed their results to our platform, anywhere. These results are community action plans that outline (a) the necessary changes in the world, (b) who is best positioned to drive them, and (c) the local steps the community can take to contribute.

The challenge is not just diversifying communication formats but rethinking who they serve and how they enable collective action. As Diaz Bordenave puts it, “The vision is the participatory society.”14 Yet while we aim for both global influence and local impact, our data presentations often default to the abstract language of institutions, whereas the work of Fals Borda and Vío Grossi underscores the need to use modes of communication that help communities better drive meaningful change themselves, not only those that suit institutions.

Creative formats, such as comic books, visual art exhibits, or performances, can bring assembly insights to life and engage the broader public. In the spirit of Fals Borda, we could systematize aggregated research and amplify local stories through their voices and voices of community heroes. For this, we could draw on well-established methods like participatory photography, handing cameras to communities so they can capture their own perspectives, advocate for themselves, and lead their own storytelling. In the spirit of El Canelo, we should not forget the importance of celebrating people’s creativity, perhaps with a twenty-first century version of a fair.

Creative translations should not only make the data more relatable but also help spark curiosity and structured debates about the themes explored in the assemblies. Fals Borda’s work with organizers on systematic devolution demonstrates the importance of dialogue between researchers and local assemblies, whether in supporting local activism, organizing more climate assemblies, or finding new ways to enact ideas born from their deliberation aimed at mobilizing political actions around climate change. We are currently mapping post-deliberation actions with our global partners and turning them into reflection prompts to help organizers support communities in planning political follow-ups. Our collaborator, Pete Bryant, is also leading work on how to nurture action after assemblies.

If all goes well, we could end up with several thousand citizen actions that present technical and political challenges, not least of which is how to communicate the outputs in a meaningful way. As I have mentioned elsewhere, we have been pushing for a participatory form of analysis, inviting advocacy groups and NGOs to engage directly with community action plans as “data partners” that will help interpret community action plans.15

For example, we could explore how to transform specific assembly insights (such as novel ideas, notable quotes, or aggregated analysis) into tangible advocacy artifacts and toolkits, such as posters. Or better yet, learning from El Canelo de Nos, we could map how community assemblies themselves invent ways to organize politically. We could then systematize, share, and celebrate their “organizer technologies.” To support this, we are not only capturing methodological innovations within the platform so the interactive dashboard can highlight user-led innovations, but we are also emphasizing community building by organizing inter-community workshops throughout the process to share insights.

Even so, we are not working alongside communities to challenge power structures, as Fals Borda, Vío Grossi, and others did. That vital work belongs to organizers on the ground. What we can do is amplify local priorities through local storytelling, but we are not part of these stories; we are not there with them.

This should humble us and push us to support and be challenged by the new Orlandos and Franciscos. We must also recognize our own power asymmetry and the barriers to establishing trust: Communities have the right to refuse, own , and control their data (see The First Nations Principles of Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession or OCAP®), a right too often ignored in big data analysis.16

Overall, once we challenge the knee-jerk resort to institutional reports in science communication, a whole new world opens. But as the often overlooked practices of Latin American PAR show, the issue is not that reports are insufficiently engaging or innovative; it is that they are not designed for the agency of communities themselves. Therefore, the political objectives of communicating beyond reports should incorporate these three main lessons:

- Community-centered communication should empower local leaders as the storytellers of their own communities.

- Organizers should map and celebrate local creativity in the most tangible way possible.

- Communication should serve as a catalyst for bottom-up organizing, not just aggregate reporting.

Inspired by the work of Orlando Fals Borda, Francisco Vío Grossi, and Oscar Nuñez, let us use participatory design and the communication of knowledge otherwise to support the people working on the ground, building trust with communities and becoming part of their stories.

—

Header image: Left image. Ulianov Chalarka drawing “El Mello” in Aguas Negras (1973). Sourced from CDRBRM, Colección fotográfica, 1945. Right image. El Mello introducing the story of Felicita Campos (1974). Caption: “Fellows: Black people are also part of the struggle of the Colombian people. Since they brought us as slaves to Cartagena, Berruga and Tolú we began to fight humiliation and exploitation. This history had never been told by the landlords or the bourgeoisie because it goes against their interests! For this reason, we are going to tell you what happened in the region of San Onofre, Department of Sucre.”

—

Iñaki Goñi: Iñaki is a Science, Technology and Society (STS) researcher focused on the relationship between technology and democracy. LinkedIn; Bluesky.

More articles in Rethinking Science Communication will be posted over the next month. Subscribe/purchase this issue to read it today.

Notes

- “Coalition for a Citizens’ Global Assembly,” accessed May 20, 2025, https://www.gcacoalition.org/

- Ernesto Guadamuz López, “La Investigación-Acción Participativa: Sus Bases Conceptuales y Metodológicas,” Revista ABRA 1, no. 15–16 (October 14, 2019), https://revistas-colaboracion.juridicas.unam.mx/index.php/abra/article/view/37557.

- João Carlos Costa, Lourdes López, and José Taberner, “Pluralismo Epistemológico, Ciencia Participativa y Diálogo de Saberes Como Medios de Renovación Cultural,” Culture and Education 12, no. 1–2 (2000): 181–87, https://doi.org/10.1174/113564000753837287.

- Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 30th Anniversary ed. (New York: Continuum, 2000).

- Juan Díaz Bordenave, “La Sociedad Participativa,” Chasquí: Revista Latinoamericana de Comunicación, no. 32 (1989): 18, my translation.

- Orlando Fals Borda, “Democracia y Participación: Algunas Reflexiones,” Revista Colombiana de Sociología 5, no. 1 (1987): 38 (my translation), https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/recs/article/view/8654.

- Joanne Rappaport’s “Cowards Don’t Make History: Orlando Fals Borda and the Origins of Participatory Action Research” offers both a more detailed account to date of the actual methods used by Fals Borda and also a synthesis of Rappaport and colleagues’ previous work of reconstructing his intellectual legacy. For a graphic novel version of her work, I recommend Historieta Doble: A Graphic History of Participatory Action Research.

- Joanne Rappaport, “Introducción a La Edición Especial de Tabula Rasa: Orlando Fals Borda e Historia Doble de La Costa,” Tabula Rasa, no. 23 (2015): 11–21, https://www.redalyc.org/journal/396/39643561001/html/.

- Joanne Rappaport, Cowards Don’t Make History: Orlando Fals Borda and the Origins of Participatory Action Research (Durnham: Duke University Press, 2020), https://books.google.cl/books?id=p2n9DwAAQBAJ; Normando Suarez, “Recuperación Crítica y Devolución Sistemática Del Retorno a La Tierra de Orlando Fals Borda,” Collectivus: Revista de Ciencias Sociales 7, no. 1 (January 1, 2020): 11–24, https://doi.org/10.15648/COLLECTIVUS.VOL7NUM1.2020.2528.

- Suarez, “Recuperación Crítica”; Rappaport, Cowards Don’t Make History.

- Ulianov Chalarka Grijales, Historia Gráfica de la lucha por la tierra en la Costa Atlántica, (Montería: Fundación del Sinú), Banco de la República: Biblioteca Virtual, accessed May 20, 2025, https://babel.banrepcultural.org/digital/collection/p17054coll2/id/71.

- I’m disappointed by the lack of systematized information on El Canelo. My understanding comes from a handful of sources, including the excellent Memoria Digital initiative, academic works by Francisco Vío Grossi and Oscar Nuñez, and informal conversations with Francisco Vio Grossi.

- Carolina Cox Melane and Gladys Ahumada Mazuranich, El Canelo de Nos: El Papel de Los Medios de Comunicación Alternativos En Su Actividad Como ONG Rural (Universidad de Chile, 1996), https://repositorio.uchile.cl/handle/2250/202164; According to Oscar Nuñez (1999), peasant technologies “encompass all specific technical arrangements that serve the goals of peasant self-subsistence and development within their particular ways of life. In other words, it includes any technological achievement that helps ensure family stability, minimizes risks, utilizes low-cost resources, and maximizes the use of family labor. Peasant technologies have very specific design characteristics: They are produced on a small scale and maintained and managed locally. They are conceived to be simple, which facilitates maintenance and repair. At the same time, they make maximum use of local materials and resources, as well as renewable energy sources such as animal power, hydraulic, solar, and wind energy” (my translation).

- Bordenave, “La Sociedad Participativa.”

- Iñaki Goñi, “Make It Make Sense: The Challenge of Data Analysis in Global Deliberation,” Deliberative Democracy Digest (Canberra, October 12, 2024).

- Jonathan Zong and J. Nathan Matias, “Data Refusal from Below: A Framework for Understanding, Evaluating, and Envisioning Refusal as Design,” ACM Journal on Responsible Computing 1, no. 1 (March 20, 2024): 1–23, https://doi.org/10.1145/3630107; Joanna Radin, “‘Digital Natives’: How Medical and Indigenous Histories Matter for Big Data,” Osiris 32, no. 1 (January 1, 2017): 43–64, https://doi.org/10.1086/693853/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/FG2.JPEG.