Re/doing Sciences in the Sundarbans Delta

By Pratyasha Nath and Jenia Mukherjee

Volume 27, no. 1, Rethinking Science Communication

What does it mean to do science in a place in constant flux like the Sundarbans? How can science communication be reimagined in a place where the boundaries between land and water are ever-changing, where communities live at the frontlines of catastrophic climate events, and where scientific knowledge often arrives from outside as rigid policies rather than as lived, adaptable practice? An ongoing collaboration between researchers from the Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur and members of Sundarban Jana Sramajibi Mancha (SJSM), a grassroots organization in the Sundarbans, is an interesting case study in rethinking how science is produced, communicated, and made actionable. At the core of the effort is the Knowledge-to-Action (K2A) project, which is defined by a radical, community-driven approach to science communication.

One of the key interventions in this collaboration is the use of adda (a Bengali term that describes informal, barrier-free conversations) as a research method. Through adda with the fishers of Kumirmari, accounts of scientific interventions like inland aquaculture emerged from the lived realities of the people, challenging the dominant narratives that frame the Sundarbans as a site of ecological risk, where human presence is seen as a threat to conservation efforts. Local communities have been actively innovating and adapting to their changing environment as agents of agroecological change instead of just being passive victims of climate change. By co-producing knowledge with fishers, rooting visually enriched training materials in local aesthetic sensibilities, and ensuring that scientific outputs are usable and accessible, a more just and participatory model of science communication has emerged, one that does not simply inform but empowers.

A Delta of Many Lives

The Sundarbans are the largest contiguous transboundary mangrove delta in the world, 40% of which belongs to India and 60% to Bangladesh. It is one of the richest biodiversity hotspots of the world, hosting over 200 additional non-tree plant species, more than 400 different species of fish, over 300 species of birds, 59 species of reptiles, 49 species of mammals including the iconic Royal Bengal Tiger, as well as countless benthic invertebrates, bacteria and fungi.1 The delta is climate vulnerable, drawing international focus such as in Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) reports, generating anxieties among scientists on the submergence of landmass, and leading to scientific conservation efforts to mitigate climate crises.

Climate science mostly revolves around the risks of living in a flood-prone, cyclone-ravaged region. Conservation of this rich ecology focuses on tigers, ecotourism, emigration, mangrove transplantation, construction of concrete embankments and funding approvals for cyclone centers. More recently, ‘managed retreat,’ which involves moving people and communities from the region, reclaiming it back to wilderness, has been proposed in scientific and policy circles. The description of the region as a wild, uninhabitable place has historical precedents from British colonial times. Unfortunately, the ‘wilderness’ discourse is not anchored in the larger understanding of the Sundarbans as a ‘social-ecological system’ comprising three key components: a social component (people), an ecological component (mangroves), and an intermediary component (local ecological knowledge and stakes) by which the interactions are facilitated.2

Within this context, we foreground the need for integration and implementation sciences that recognize multiple ways of knowing and doing, borrow from both mainstream epistemes and place-based practices, and allow and foster cross-fertilization for sustained results. We showcase an example of how this exercise yields results, supporting cross-learning opportunities between fishery scientists and fisher communities in one of the remotest island villages of the Indian Sundarbans.

Kumirmari: A Village on the Edge

The Indian Sundarbans comprise the Sundarbans Biosphere Reserve and the Sundarbans Tiger Reserve; the former covers an area of 9,630 square kilometres of which 4,263 square kilometres are uninhabited forest and the remaining 5,367 square kilometres are a densely populated transition zone. It is an ever-changing island archipelago that is partly forested and partly inhabited. The Sundarbans is not a homogenous socio-ecological system—the Southern blocks are more susceptible to climate risks than their northern counterparts. This is in part due to their remote location and physical volatility, but also due to intentional economic marginalization arising from the reluctance of people in power to improve livelihoods and make infrastructural interventions.

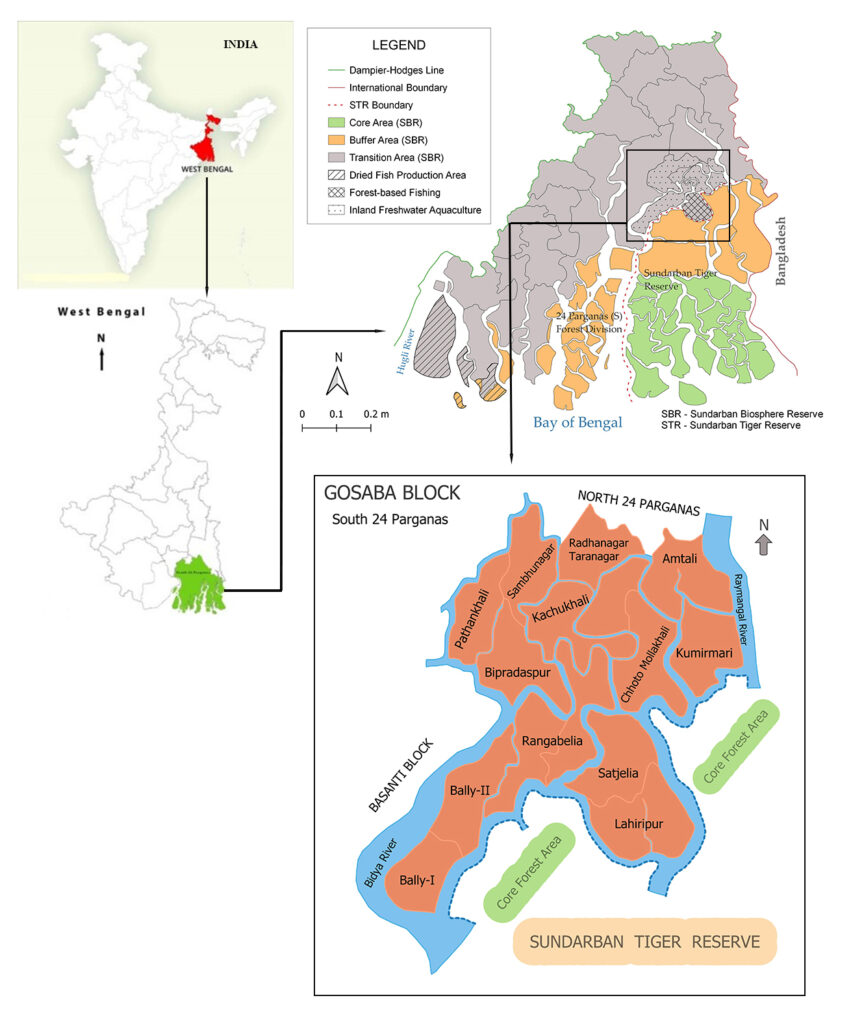

Kumirmari is one of the remotest island villages in the southernmost block of Gosaba, in the South 24 Parganas district of West Bengal (Figure 1). In 2020, Cyclone Amphan devastated the Kumirmari island village and its neighbouring islands such as Satjelia and Lahiripur, making Gosaba one of the worst-affected blocks. The ongoing nationwide lockdown owing to the COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated the situation. After losing their jobs owing to the suspension of economic activities, migrant workers returned home to equally uncertain futures with homesteads and traditional livelihoods destroyed. Increased soil salinity disrupted agriculture and fishing, leading to a greater dependence on forests. Collecting forest produce like honey or fishing for crabs has its own risks: attacks by tigers and victimisation by tiger-conservationist forest officials. Venturing into the forest brings the villagers in the line of fire of the Royal Bengal Tiger’s inter-island migration patterns and of the forest officials who are tasked with conserving this species. Access to the forest is regulated on a model of deprivation, dispossession and exploitation where the Tiger is at the top and the villagers at the bottom of the priority list. “We are afraid of the forest officials more than the tigers,” is an oft-repeated sentiment among forest fishers.

Moreover, regulations governing access to forests have played a primary role in the deprivation, dispossession and exploitation of village communities. Though forest fishers are permitted to catch fish against valid boat licence certificates issued by the state forest department, yet, stringent forest bureaucracy and corrupt intermediaries have made forest fishing a risky and life-taking venture.

Riskscape to Resilience: The Community Speaks

Kumirmari has a growing exposure to climate hazards, like many other remote islands of the southernmost block. Yet it is different in that it shows signs of material prosperity and community aspirations despite the impending crisis. Its population consists of marginalized social groups such as immigrants from Bangladesh and adivasis in addition to religious and caste minorities.3 Kumirmari has 4344 households, of which approximately 3000 own ponds in their household premises. The locals use these ponds primarily for inland fish farming. After cyclones, fish disease, inappropriate fish seeds, and prolonged salinisation of land disrupt the well-being of fishers. The villagers expressed their concerns about inadequate knowledge of how to continuously adapt and adjust to these challenges, asserting the importance of gaining scientific expertise. The concerted efforts of the fishers, the availability of ponds for most households, a willingness to adopt inland fishing as the major source of income and the desire to be trained in adaptive fishing practices brought Kumirmari to the attention of a team of researchers from the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Kharagpur.

When the team of social science researchers initially arrived in Kumirmari, the plan was simply to use established methods of qualitative research to document and assess the riskscape of the Indian Sundarbans. However, beyond the boundaries of pre-set questionnaires and surveys, it was through adda that the villagers described their efforts in pursuing situated agro-ecological adaptive practices against climate crises and related constraints. They shared personal accounts of their collective readiness to switch to inland fishing (the term commonly used in the region for raising fish) in the face of climate and legal risks. The immediate need identified was the development and distribution of a training module based on jointly produced knowledge and conveying best practices of inland fishing to support climate resilient livelihoods provisions and profits.

Transcending Disciplines: From Knowledge to Action

IIT Kharagpur and SJSM came together to co-create recommendations on best practices in aquaculture. They also brought in experts from the Central Inland Fisheries Research Institute (CIFRI) to integrate mainstream limnology with situated practices. The villagers insisted on the importance of gaining scientific expertise through easily accessible, village-level programs where the ordinary fisher could directly interact with subject matter experts from the Department of Fisheries, the Government of West Bengal, and other technical organisations. Small grant opportunities were harnessed from the Swissnex K2A initiative, supporting academic research outputs into tools and processes that support awareness, advocacy, and transformation of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.4

The K2A project progressed in two phases. Between September 2021 and June 2022, fishers from Kumirmari, SJSM, local panchayat members, principal scientists from CIFRI and the IIT Kharagpur team participated in a series of in-situ knowledge exchange workshops. Dialogues among people from diverse social affiliations optimized opportunities for learning together, generating moments of wonder and awe and pushing the knowledge frontiers of both fisheries experts and local fishers. While experts were amazed by local skills in preparing fish feed using local ingredients such as mustard oil cakes, rice bran, nuts, etc., the use of urea and Di-Ammonium Phosphate in plankton bloom was unknown to the community. Moreover, expert training on right amounts, right dosages, and right timings enabled small yet significant interventions in shaping best practices of inland fisheries. The IIT researchers systematically and rigorously documented the dialogues and discussions. The key motive was to design a place-based inland fishing training manual, integrating mainstream scientific knowledge on inland fisheries with the practice-induced knowledge of the local communities. A prototype manual was indeed developed, but the locals agreed to accept it only if it was validated in a real-world experiment. As was said, so was done!

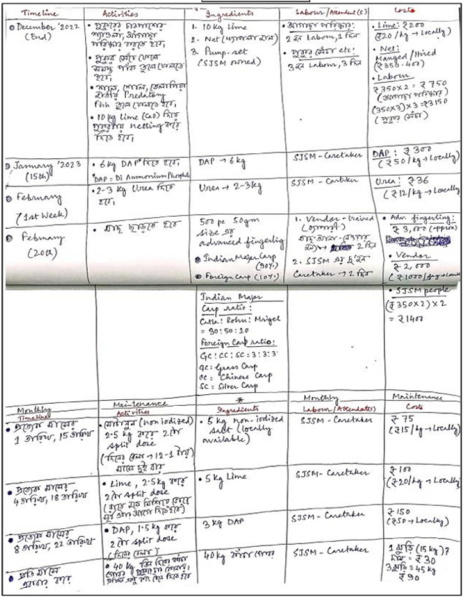

We conducted hands-on inland fishing experimentation in a pond at the SJSM premise between March 2023 and January 2024, preceded by preparatory workshops on inputs and investments between July 2022 and February 2023. The transdisciplinary team prominently featured resident fishers who actively helped the team of researchers in recording the results generated from the step-by-step experiment. In hindsight, the entire process was documented to analyse the validity of the prototype training manual. The academic team in consultation with SJSM volunteers prepared a template in Bangla to simplify the implementation steps starting from pre-production stage to production, post-production. They attempted to list down every micro-detail of the process, including instructions on inputs, dosage of ingredients, timings of activities, and roles of SJSM volunteers involved in the experiment (Figure 2). The academic team minutely documented deviations and departures from the expected procedures and outcomes mentioned in the prototype training manual. In the evenings, we discussed at length the future of this experiment in terms of generating and distributing profit. When we seemed puzzled with some burning questions about the viability of this exercise due to inadequate market linkage, lack of cold storage, etc. in remote Sundarbans, assuring remarks from the more experienced scientists of CIFRI evoked sighs of relief!

In January 2024, the very first harvest (header image) of experimentally farmed fish was weighed. The different fish varieties showed almost 6.6 times bigger growth from their original size since the time of release, a number confirmed to be impressive by the scientists from CIFRI. Experts from the Department of Fisheries, Government of West Bengal, also backed this opinion.

A Visual Language of Change: Designing for the Community

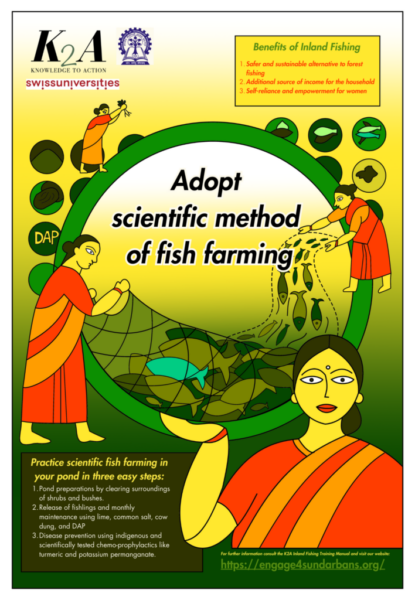

The scientific output planned was a bilingual, infographic rich prototype training module. Women members of the grassroots organization demanded visual illustrations which they said would support the village women who were keen to pursue fishing in their domestic ponds to generate safe and convenient livelihoods. Adopting key lessons from the pond experimentation at the SJSM campus, some women members not only initiated aquacultural practices in their respective household ponds but also collectively engaged with women members from self-help groups in the village, demonstrating effective principles of leadership and knowledge mobilization. The importance of using the appropriate visual dialect in scientific outreach material was established by gender. For the longest time, words have been considered the superior currency of intellect. The reliance on the written word is so pervasive that one does not even realize one’s role in perpetuating it.

Designing the one-page poster for the community of Kumirmari was far from a straightforward task; it was an evolving journey shaped by continuous dialogue and exchange with the local people, particularly the women fishers. The initial ideas were just starting points—each iteration was a step toward creating something that felt authentic, relatable, and deeply rooted in the visual culture of the Sundarbans. We began with a general concept, inspired by observations and sketches from the field, but soon realised that our understanding of what might resonate was limited. Armed with this understanding, we went back to the drawing board—literally—and began experimenting with these colors as the foundation of the design. The first drafts, however, fell short. The feedback was polite but clear: the composition was right, but the colors felt off. It was too formal, too detached and too urban. We had to rethink how to balance the vibrancy with relatability, how to draw in colors that were immediately recognizable to the community. The people of Kumirmari, particularly the women who live and work in this environment every day, have a visual dialect all their own—a vibrant, expressive aesthetic that speaks through colors, patterns, and textures unique to their daily lives and surroundings. We knew that we needed to reflect this in our design. From the very start, we engaged in conversations with the women fishers to understand their preferences and cultural visual language. They were instrumental in steering the design. They favoured bold, saturated colors—greens that echoed the dense foliage of the mangroves, reds and oranges that mirrored the hues of their sarees, and the bright yellows that punctuated their everyday environment. These colors were more than mere preferences; they were part of their identity, woven into the very fabric of their lives.

The process became more collaborative from that point. We found ourselves doing a lot of back and forth, taking sketches and drafts back to the women fishers, asking for their input, listening to their stories, and observing how they responded to different visual elements. They pointed out small details—like the way we had rendered the water or the patterns we had used for the nets. They corrected us, offered suggestions, and guided us in ways that transformed the design. They wanted the poster to feel like it came from within their world, not as an outside observation.

Gradually, the design began to take shape. The composition was reworked to highlight the women fishers, placing them prominently and giving visual weight to their activities—clearing the pond surroundings, releasing fishlings, and catching the harvest. The colors grew richer and more saturated with each iteration, echoing the hues they loved. The elements became less abstract and more representative of their daily realities. The use of local motifs, like the weave of their fishing nets and the design of the local deities, started to find their way into the design.

The final version of the poster was not a single act of creation but a result of an ongoing, iterative process—one that was steered by the community itself. The design choices were shaped by countless conversations, observations, and the invaluable feedback of the women whose stories and lives we sought to amplify. What emerged was a poster that was not just about them, but one that felt like it was truly from them—a piece of visual storytelling that carried their preferred colors, their visual dialect, and their spirit.

Looking back, this iterative process was more than just a series of revisions; it was an exercise in learning to see through the eyes of the community and to co-create in a way that honored their voices, choices, and identities. The poster became a living document of our shared engagement—a vibrant, colourful testament to the power of art and design as a collaborative tool for connection and communication.

Training manuals laden with text and at best some technical diagrams, have been introduced and discarded routinely in Kumirmari. Various departments of the state and some NGOs had gained a patchy reputation for their infrequent and insufficient efforts in providing training programs and distributing manuals. Simply making people aware is no longer enough! Diverse knowledge practices, along with place-based participatory actions, creates an awareness that has long-term credibility against technocratic solutions that are merely transplanted from one place to another. The Kumirmari story explicitly attests to this.

Towards a more just Science Communication

The fishers of Kumirmari co-produced knowledge and felt empowered and confident to conduct pisciculture in ponds by blending place-based and conventional-mainstream fishery practices. The Sundarbans example is an enabler in decolonizing science with equal consideration given to the contributions of different knowledges and ways of knowing.

In the emerging discussions on the role of transdisciplinary sciences in transformative change, the Kumirmari example offers some directions. Beyond the vicissitudes of hegemonic science, transformative sciences create enabling conditions, contexts, and capacities within communities as forerunners of change – where the latter are not portrayed as mere victims of climate change but coping actors transitioning into adaptive managers of the future.

The climate hyperbolic mainstream scientific narrative of the Sundarbans has not only reduced the 4.5 million human inhabitants to a mere afterthought, a footnote in climate adaptation policies, but also as a population that is seen as better off relocated to “safer” mainland locations to maintain the “pristineness” of the internationally famous abode of tigers and other wildlife. Science cannot be a regurgitation of climate anxiety propaganda aimed at displacing Indigenous communities but a way forward in crafting social resilience inhabiting volatile ecologies during the Anthropocene. By spearheading the discussions and experimenting on an equal footing with members of academia and other stakeholders, the community has offered a starting point to shift the sci-comm talk in the Sundarbans from risks of the delta to agroecological innovations.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Cluster of Cooperation (CLOC) Knowledge to Action (K2A) Small-Scale Grants in South Asia through which the pond fishing experimentation was initiated. Field work during 2024 and contingencies have been supported by funding from the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) and the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) under the Solution-oriented Research for Development program (www.sor4d.ch), project no. 400440_213316 Social resilience in the Sundarbans Delta: Eliciting Needs-based Grassroots Action through Cross-Group Engagement (ENGAGE), a SOR4D—Solution-oriented Research for Development programme.

—

Jenia Mukherjee, PhD: My research interest spans across environmental humanities and transdisciplinary waters. I am currently investigating several global partnership projects on social livelihoods in coasts and deltas. I believe that the efficacy of the social researcher lies in recognizing the agency of everyone and everything that inhabits this planetary system and beyond! Facebook

Pratyasha Nath: Pratyasha is a visual artist and a final year student of Biotechnology at the Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur. Currently she is curating an exhibition on flood narratives from the Indian Sundarbans as part of the IHE Delft funded AQUAMUSE project. She combines her love for storytelling and the sciences to explore the relationship between humans and nature in her comics and paintings. Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn

Notes

- Amrita Sen, et al., “For, Of, and By the Community: Critical Place-based Reflections on Mangroves Regeneration in the Indian Sundarbans,” Community Development Journal, (December 24, 2024), 1-19.

- Amanda Manyani, et al., “The Evolution of Socio-ecological System Research: Co-authorship and Co-citation Network Analysis,” Ecology and Society, 29 no. 1(2024), Article 33.

- Adivasi is a collective term to designate different/heterogeneous tribes and ethnic groups considered to be original inhabitants of the Indian subcontinent.

- The K2A project is funded by the Swiss Universities Development and Cooperation Network (SUDAC) program where South Asian researchers execute short duration projects on ecological sustainability and social wellbeing.